Boat Plans, Patterns and Supplies For the Amateur Boat Builder!

- Boat Plans Catalog – 300 Boats You Can Build!

- Boatbuilding Supplies & Epoxy

- Inboard Hardware

- Electrical Design Plans

- Books, DVD’s & Audio

- Boat Trailer Plans

- Raptor® Fastenings & Tools

- Glen-L RV Plans

- Gift Certificates

- Boatbuilder Blogs

- Boatbuilder Galleries

- Newsletter Archives

- Customer Photos Archives

- Where Do I Start…

- About Our Plans & Kits

- Boatbuilder Forum

- Boatbuilder Gatherings

- Boatbuilding Methods

- Featured Design on TV’s NCIS

- Our Boats in Action

Small boat kick-up rudder

Rigging small sailboats.

….. deck fittings

Some comments on winches have been made previously. The variety and type of winches available to the sailor is enormous, but for the small boat sailor, winches usually are restricted to the smaller sizes used to control the jib and Genoa sheets. Winches can be used for the halyards, boom vang, and mainsheets, if desired. On small boats the cost is usually prohibitive, and the extra power gained is not required, as these lines can be handled by the crew or by other means, such as tackles, equally well.

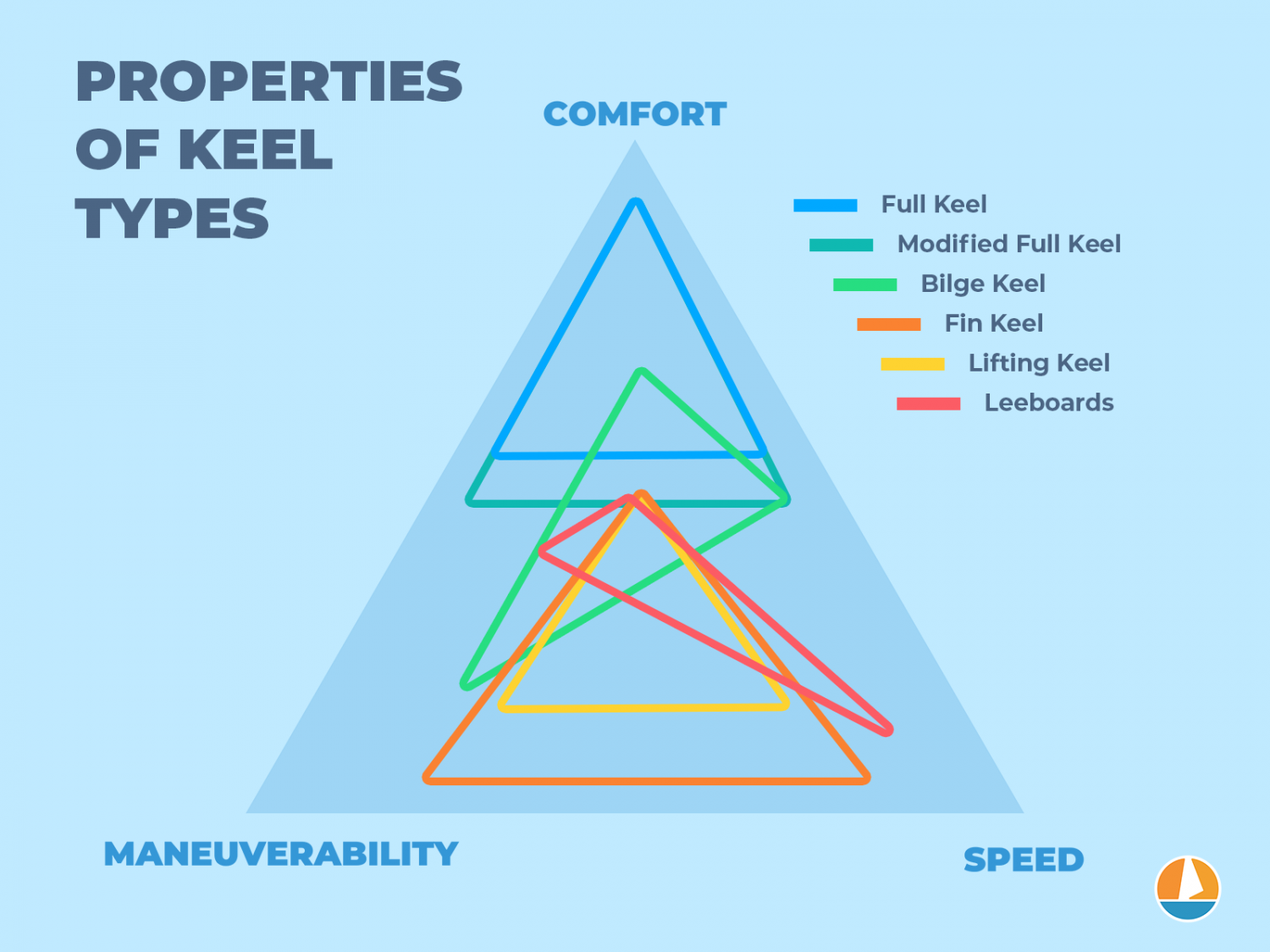

RUDDER FITTINGS

Small sailboats usually have rudders which are called “outboard” rudders because they hang onto the aft end of the boat in full view. Boats which have rudders under the hull and the rudder stock passing through the hull bottom are said to have “inboard” rudders, but these are usually associated with large boats. The ordinary small boat rudder is attached to the boat with fittings that also allow the rudder to pivot or turn. These fittings are called GUDGEONS and PINTLES. These are arranged in pairs, with the gudgeons usually being attached to the boat, and the pintles fastened to the rudder. The pintles are strap-like fittings with the rudder fitting between the straps, and with a pin at the forward edge which fits into the “eye” of the gudgeons (see Fig. 6-10). As with most fittings, many sizes and types are available. Often gudgeons and pintles come in pairs which have a long pintle and a shorter one. These types make it easier to put the rudder on the boat, as the long pintle will be in position first, thereby acting as a guide for the short one. If both pintles are the same length, both must fit into the gudgeons at the same moment, which is frustrating at times, especially when trying to place the rudder in position when afloat. Because many small boat rudders are made of wood, the tendency is for these to float up and out of the gudgeons, of course, making for an immediate loss of steering and much embarrassment. A device called a RUDDER STOP can be used to prevent this from occuring. These are standard marine hardware items very simple in nature.

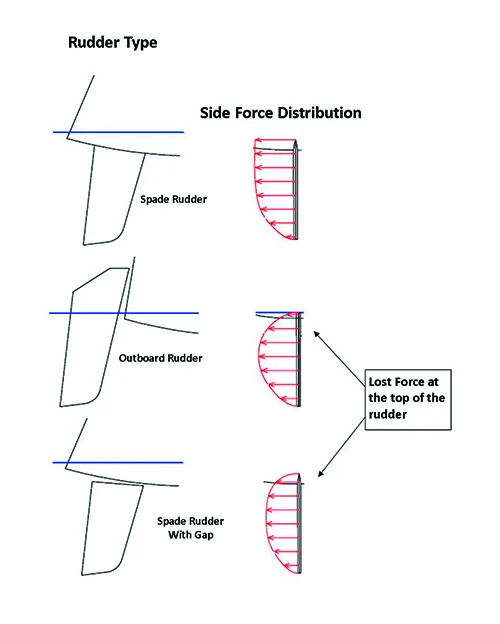

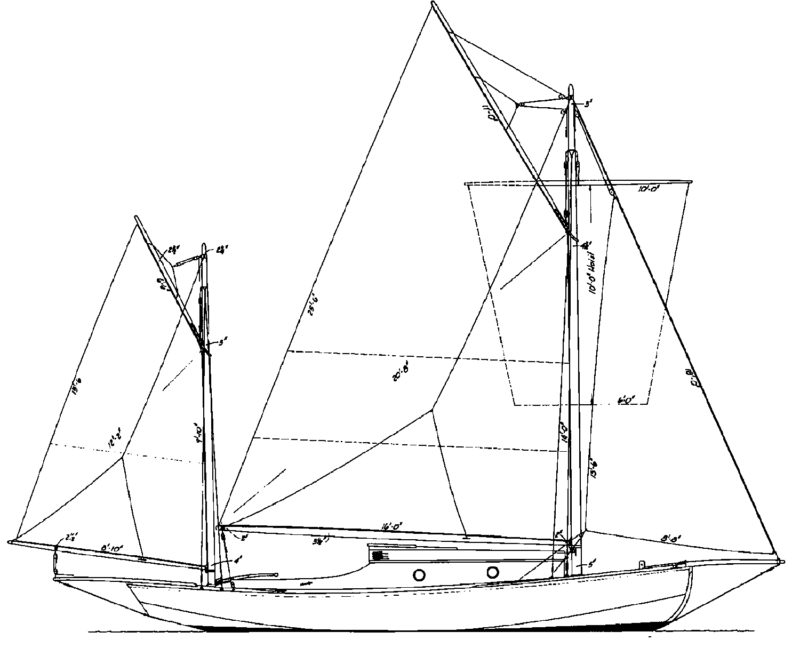

For small sailboats which land on the beach, it is desirable to have the rudder “kick up” when approaching shallow waters. Special “kick-up” rudder fittings such as shown in Fig. 6-11 are available, which also have the gudgeons and pintles attached as an integral unit, and perform this function. With a little effort, you can make your own “kick-up” rudder similar to the detail shown in Fig. 6-12.

FIG. 6-12 – One method of making a kick-up rudder using wood. When the pin is removed, the rudder will automatically come up when hitting the beach.

FIG. 6-13 – This tiller extension was made by merely cutting the tiller in half at the forward end and fastening it with a bolt. A more convenient type uses a swivel connection in lieu of the bolt for universal action. The line shown is a rope traveler which can be adjusted in length and is secured to the jam cleat on the deck.

The rudder is controlled by a handle called the TILLER. Sometimes the tiller passes through a hole in the transom (back of the boat), but usually it is located above the aft deck area and pivots up and down so the crew can move about easily. The length of the tiller is best determined in actual use, so it should be made longer than necessary. It’s much easier to cut off a long tiller than to add length to a short one. A device recommended for easier control, especially when tacking or sailing to windward, is a TILLER EXTENSION or “hiking stick,” an example of which is shown in Fig. 6-13. When sailing to windward in a small boat, the boat usually heels considerably and the crew must lean out to windward (or “hike out”) to counteract this. In order to hang onto the tiller in this position, an extension is required, fixed to the forward end of the tiller and preferably fitted with a universal-type joint. Naturally, the length of such a unit is best determined in actual use, so it is best to get a long one which can be cut, instead of getting one too short which can’t be added to.

The next WebLetter will start Part II …how to install the rigging.

Comments are closed.

Connect with us:

Customer builds.

Useful Information

- Cost & Time To Build

- Links & Suppliers

- Online Glossary

- Support Knowledge Base

- Teleseminars

- Wood & Plywood

Building Links

- How Fast Does It Go?

- Install A Jet Ski Motor

- Modifying The Motorwell

- Sailboat Hardware Notes

Glen L Marine Design

- About Glen L

- How To Place an Order

- Privacy Policy

Copyright Info.

Copyright 2006-2022 by Glen L Marine Designs. All rights reserved.

Mailing Address: 826 East Park Ave. Port Townsend, WA 98368

Web design by Big Guns Marketing , LLC.

Small Craft Advisor

Build Your Own Kick Up Rudder

William mantis offers up plans for a creative and effective diy rudder.

by Bill Mantis

I built a rudder for my 8.5’ x 4.5’ sailboat—named City Slicker 2. 0—the same time I built the boat itself, two years ago . Since I was in a hurry to get it done, I didn’t bother designing a kick-up rudder, figuring I could make the modification at a later date. But then I lost it. I lost my rudder. How does one lose a rudder? I can’t explain how it happened. I only know I had it when I came ashore one day, and didn’t have it the next time I tried to launch. Fortunately, I’d been designing a kick up rudder before suffering the loss, and I had the necessary epoxy and lumber on hand. Only the material for the rudder blade and new pintles had to be ordered. As a result, I lost only one week of the sailing season.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Small Craft Advisor to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Pay My Bill

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

- Give a Gift

How to Sell Your Boat

Cal 2-46: A Venerable Lapworth Design Brought Up to Date

Rhumb Lines: Show Highlights from Annapolis

Open Transom Pros and Cons

Leaping Into Lithium

The Importance of Sea State in Weather Planning

Do-it-yourself Electrical System Survey and Inspection

Install a Standalone Sounder Without Drilling

When Should We Retire Dyneema Stays and Running Rigging?

Rethinking MOB Prevention

Top-notch Wind Indicators

The Everlasting Multihull Trampoline

How Dangerous is Your Shore Power?

DIY survey of boat solar and wind turbine systems

What’s Involved in Setting Up a Lithium Battery System?

The Scraper-only Approach to Bottom Paint Removal

Can You Recoat Dyneema?

Gonytia Hot Knife Proves its Mettle

Where Winches Dare to Go

The Day Sailor’s First-Aid Kit

Choosing and Securing Seat Cushions

Cockpit Drains on Race Boats

Rhumb Lines: Livin’ the Wharf Rat Life

Re-sealing the Seams on Waterproof Fabrics

Safer Sailing: Add Leg Loops to Your Harness

Waxing and Polishing Your Boat

Reducing Engine Room Noise

Tricks and Tips to Forming Do-it-yourself Rigging Terminals

Marine Toilet Maintenance Tips

Learning to Live with Plastic Boat Bits

- Boat Maintenance

Building a Faster Rudder

Boost performance with a bit of fairing and better balanced helm..

We’re cruisers not racers. We like sailing efficiently, but we’re more concerned with safety and good handling than squeezing out the last fraction of a knot. Heck, we’ve got a dinghy on davits, placemats under our dishes, and a print library on the shelf. So why worry about perfection below the waterline?

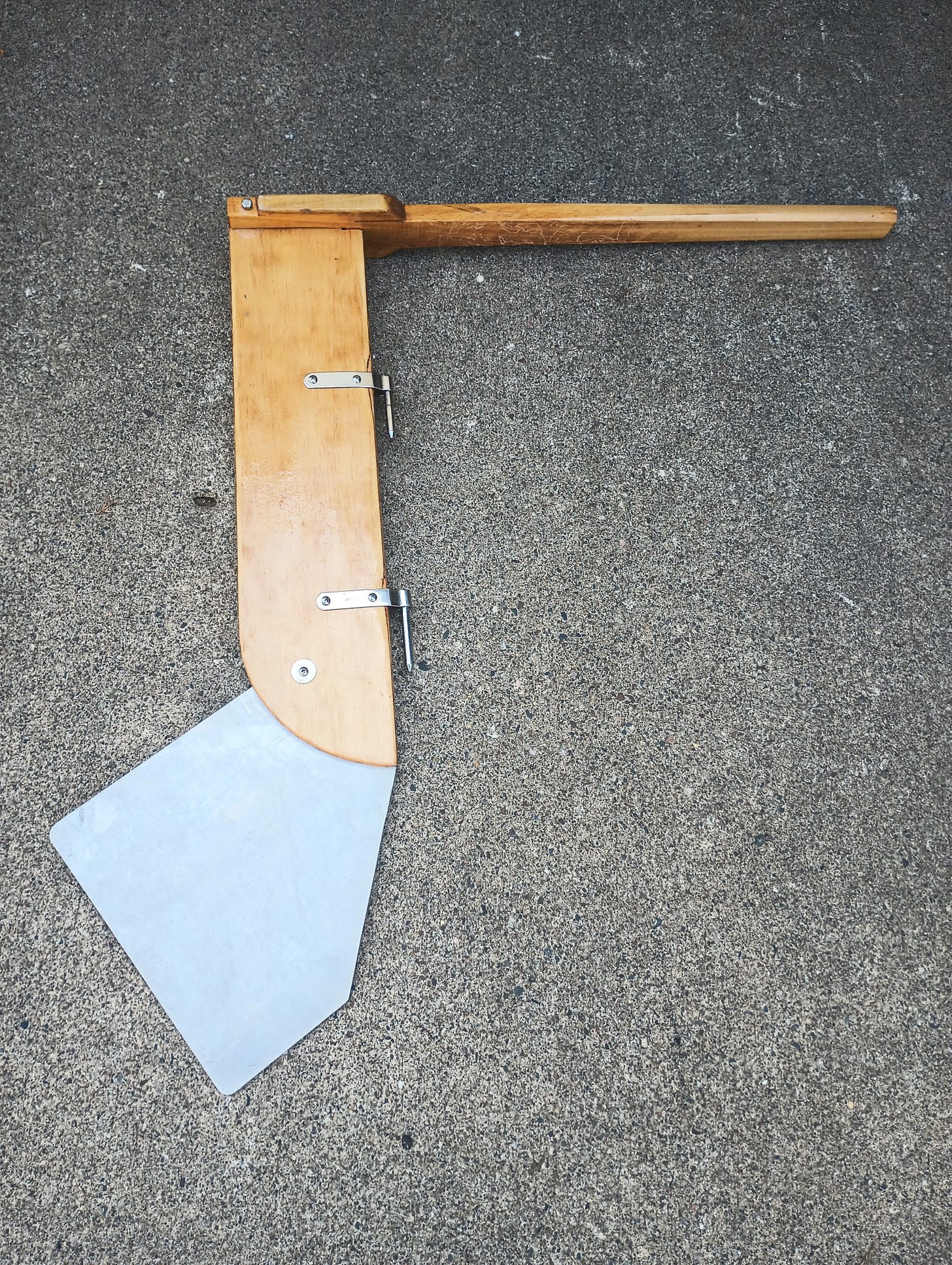

The reason is handling. A boat with poorly trimmed sails and a crudely finished rudder will miss tacks and roll like a drunkard downwind when the waves are up. On the other hand, a rudder that is properly tuned will agilely swing the boat through tacks even in rough weather, and provide secure steering that helps prevents broaching when things get rolly. The difference in maximum available turning force between a smooth, properly fitted rudder and the same rudder with a rough finish and poor fit can be as much as 50% in some circumstances, and those are circumstances when you need it the most. It’s not about speed, it’s about control.

It Must Be Smooth

Smooth is fast. That’s obvious. But it makes an even bigger difference with steering. Like sails, only half of rudder force comes from water deflected by the front side of the blade. The rest results from water being pulled around the backside as attached flow. How well that flow stays attached is related to the shape of the blade, which we can’t easily change, and to the surface finish of the blade, which we can.

Remember the school experiment, where you place a spoon in a stream of water and watched how the water would cling to the backside of the spoon? Now, try the experiment again as a grown-up, but with a different set of materials.

Try this with a piece of wood that is smooth and one that is very rough; the water will cling to the smooth surface at a greater angle than the rough surface. Try piece of smooth fiberglass or gelcoat; the water will cling even better because the surface is smoother. Try a silicone rubber spatula from the kitchen. Strangely, even though the surface is quite smooth, the water doesn’t cling well at all. We’ll come back to that.

Investigators have explored this in a practical way, dragging rudders through the water in long test tanks (US Navy) and behind powerboats.

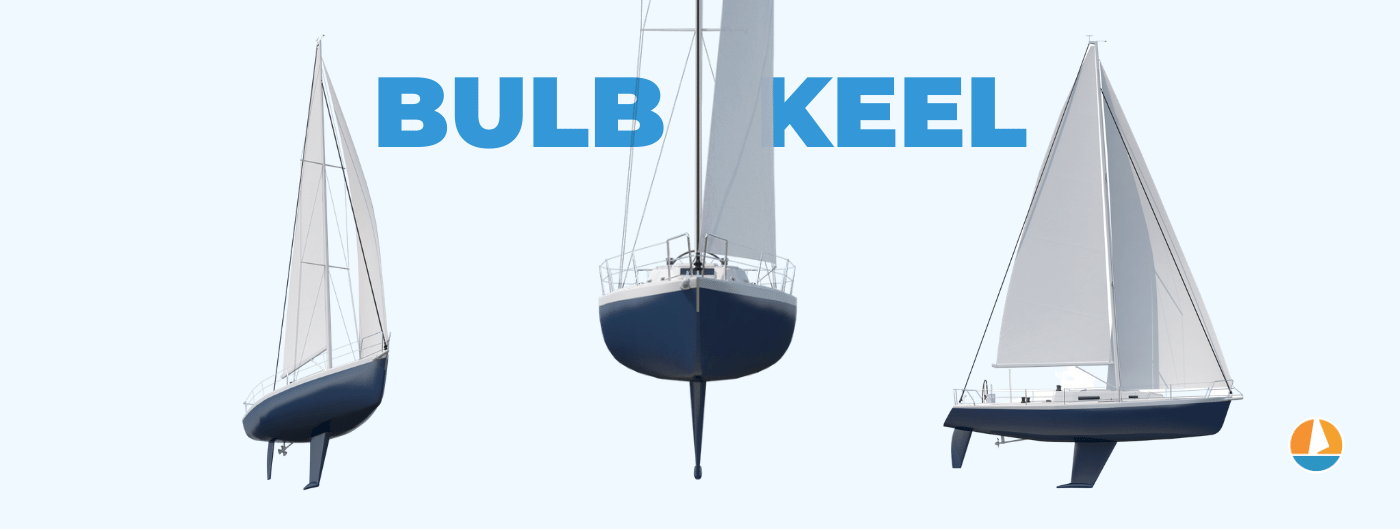

If we are trying to climb to windward, it’s nice to get as much lift out of the rudder as practical, before drag becomes too great or before it begins to stall with normal steering adjustments. If the boat has an efficient keel and the leeway angle is only a few degrees, the rudder can beneficially operate at a 4-6 degree angle. The total angle of attack for the rudder will be less than 10 degrees, drag will be low, and pointing will benefit from the added lift. If the boat is a higher leeway design—shoal draft keels and cruising catamarans come to mind—then the rudder angle must stay relatively low to avoid the total angle (leeway + rudder angle) of the rudder from exceeding 10 degrees. That said, boats with truly inefficient keels but large rudders (catamarans have two—they both count if it is not a hull-flying design) can sometimes benefit from total angles slightly greater than 10 degrees—they need lift anywhere they can get it.

How can you monitor the rudder angle? If the boat is tiller steered, the tiller will be about 0.6 inches off center for every degree or rudder angle, for every 3 feet of tiller length. In other words, the 36-inch tiller should not be more than about 2 inches off the center line. If the boat is wheel steered, next time the boat is out of the water, measure the rudder angle with the wheel hard over. Count the number of turns of the wheel it takes to move the rudder from centered to rudder hard over, and measure the wheel diameter. Mark the top of the rim of the wheel when the boat is traveling straight, preferably coasting without current and no sails or engine to create leeway.

The rim of the wheel will move (diameter x 3.146 x number of turns)/(degrees rudder angle at hard over) for each degree of rudder angle. Keep this in the range of 2-6 degrees when hard on the wind, as appropriate to your boat. It will typically be on the order of 4-10 inches at the steering wheel rim. A ring of tape at 6 degrees can help.

How do we minimize rudder angle while maintaining a straight course? Trimming the jib in little tighter or letting the mainsheet or traveler out a little will reduce pressure on the rudder and reduce the angle. Some boats actually sail to weather faster and higher, and with better rudder angles, by lowering the traveler a few inches below the center line.

On the other hand, tightening the mainsheet and bringing the traveler up, even slightly above the center line on some boats, will increase the pressure and lift.

Much depends on the course, the sails set, the rig, the position of the keel, the wind, and the sea state. Ultimately, some combination of small adjustments should bring the rudder angle into the appropriate range. Too much rudder angle and you are just fighting yourself.

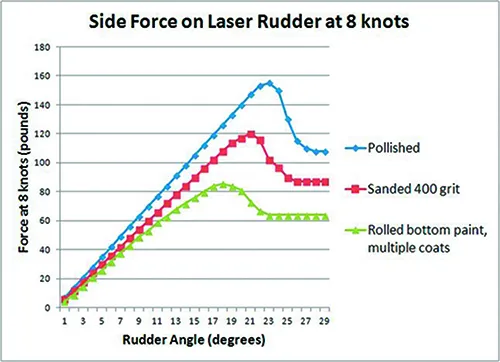

- Turn this rudder just 10 degrees and the end plate is lost, reducing the amount of lift generated.

- This rudder might as well be transom hung, the way that the end cap just disappears.

- Stern-hung rudders, and spade rudders with large gaps between the hull and the top of the rudder will lose their lift at the “tip” of the blade near the surface.

Surface roughness affects the lift from the rudder in two ways. A rougher surface has slightly lower lift through the entire range of angles, the result of a turbulent boundary layer instead of smooth flow over the entire surface. More dramatically, rougher blades stall at lower angles and stall more completely. The difference between a faired rudder with a polished finish and a rudder carrying a 10-year accumulation of rolled-on antifouling paint can be as much is 35 percent (see “Rudder Savvy to Boost Boat Performance,” above).

What can we do? If your rudder is a lift up type, don’t use bottom paint. Fair the blade within an inch of its life and lay on a gloss topside paint as smoothly as possible, sanding between coats. If you use a brush, stroke the brush parallel to the waterline, not along the length of the blade.

Which is faster, a gloss finish or one that has been dulled with 1000 grit sandpaper? Opinions go both ways, and we believe it may depend on the exact nature of the paint, which leads to the question, “Should we wax the blade?” The answer is a resounding, no.

Wax is a hydrophobic (readily beads water), like the silicone rubber spatula you tested, and as a result, water doesn’t always cling as well. Thus, whether the paint should be deglossed or not depends on the chemistry of the paint, but in all cases the final sanding should be 1000 grit or finer.

If the rudder stays in the water, antifouling paint is required. Sand the prior coat perfectly smooth. There should be no evidence of chips, runners, or any irregularity at all. Using a mohair roller, lay the paint on thin, and apply multiple coats to withstand the scrubbing you will give your rudder from time to time.

Even if you use soft paint on the rest of the boat, consider hard paint for the rudder. Sure, it will build up and you will have to sand it off periodically, but the rudder is small and no part of your boat is more critical to good handling. Take the time to maintain it as a perfect airfoil.

Close the Gap

Ever notice the little winglets on the tips of certain airplanes? As we know, those are intended to reduce losses off the tip of the wing. The alternatives are slightly longer wings or slightly lower efficiency. At the fuselage end of the wing, of course, there is no such loss because the fuselage serves as an end plate. The same is true with your rudder.

There’s not much you can do about losses from the tip; making the rudder longer will increase the chance of grounding and increase stress on the rudder, rudder shaft, and bearings. Designers have experimented with winglets, but they the catch weeds and the up-and-down motion of the transom makes them inefficient. However, we can improve the end plate effect of the hull by minimizing the gap between the hull and the rudder.

In principle it should be a close fit, but in practice the gap is most often wide enough to catch a rope. Just how much efficiency is lost by gap of a few inches? The answer is quite a lot. A gap of just an inch can reduce lift by as much as 10-20 percent, depending on the size and shape of the rudder and the speed. A gap of 1-2 mm is quite efficient, but normal flexing of the rudder shaft may lead to rubbing.

If the gap is tight, the slightest bend from impact with a submerged log can cause jamming and loss of steering, though in my experience once the impact is sufficient to bend the shaft, a small difference in clearance is unlikely to make much difference; the shaft will bend until the rudder strikes the hull. Just how tight is practical depends on the type of construction, fitting accuracy, and how conservative the designer was in their engineering.

Carbon shafts, tubular shafts, and rudders with skegs flex less, while solid shafts generally flex more, all things being equal. Normally a clearance of about 1/4-inch per foot of rudder cord is practical, and performance-oriented boats often aim for much less. If you can reach your fingers through, that’s way too much. Hopefully the hull is relatively flat above the rudder so that the gap does not increase too much with rudder angle.

Practical Sailor’s technical editor Drew Frye is the author of the books Keeping a Cruising Book for Peanuts and Rigging Modern Anchors. He blogs at his website, sail delmarva.blogspot.com .

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

21 comments.

How happy to see good technical information about the science of boat speed and control. This information is valuable to everyone, but the “mainly just cruising” cohort usually doesn’t get enough in an easily understandable form. I always suggest some club level racing as the best way to learning how to sail, but many prospective racers have been put off from the sport or haven’t had good opportunities to join the fleets. Technical seminars are generally either too advanced for beginners to understand properly, and the beginner classes are frequently too basic to inspre those who would benefit from a deeper knowledge base in the science of sailing. Good on you, Practical Sailor, for your technical stories hitting the “sweet spot,” getting this information to those we’ll benefit most.

Great article. How about considering modifying a rudder to make it a hydrodynamically balanced rudder. I did it to my boat and the difference is outstanding. If I remember correctly 7% of the rudder area is forward of pivot center. It is a skeg hung rudder that now turns like it’s a spade rudder.

I’m “skeg hung” also. Would you be so kind as to posting a link or providing info as to you accomplished this feat. Thanks!

A very clear explanation of some quite complicated hydrodynamics – thank you! I am surprised by the US Navy results showing benefit of sanding further than 400 grit. Most other experimental data suggest there is negligible advantage in going beyond about 360 grit. Is the original reference publicly available? On Michael Cotton’s comment, a couple of points: Firstly, the amount of balance (i.e how far back you put the stock in the blade) has no impact on the hydrodynamic performance of a spade rudder. What it does do is change the feel of the rudder; a well balanced rudder will be easier to use, thereby probably allowing the steerer to sail the boat better. For a skeg rudder, the hydrodynamic impact of changing the balance depends very much on how the skeg/blade combination is configured. Secondly, 7% of rudder area forward of the stock is not enough for most rudders. The position of the centre of pressure is dependent on a lot of factors (aspect ratio, rudder angle etc.), but it is usually at least 15% back from the leading edge on a spade rudder, more often 20%. A balance somewhere between 10% and 15% is likely to give just enough feel without too much weight. However, rudder balance is still a bit of a black art, it really does depend on the rudder geometry.

the statement that one doesn’t want a silicone/silane coated ( super-smooth, hydrophobic: silicone-silane is just the example I am choosing, since it is now in use as a massively-speeding hull-coating, ttbomk ), as it *induces* flow-separation…

looks to me like conflating cavitation with flow-separation.

People have no problem teflon/ptfe-coating aviation-wings, as a means of *preventing* flow-separation.

the super-slick shape of a Cirrus’s composite wing, if made super-smooth/polished & super-slippery, “air-phobic”, as it were, *improves* its performance, not detracts from it….

Flow is always 1. laminar, then 2. turbulent, then 3. flow-separation.

unless the angle-of-attack ( AoA ) is small-enough to prevent separation.

The Gentry Tufts System, for *seeing* when a separation-bubble begins, on a sail, is brilliant ( Arvel Gentry was a fluid dynamicist, & realized that once one has a *series* of tufts, from luff on back, about 1/4 up the luff, one can *see* the beginning of a flow-separation-bubble, & tune the sail to keep it *just*-beginning, because *that* is MAX lift. Wayback Machine has his site archived, btw )

The aircraft designer Jan Roskam wrote of a DC-10 crashing because pebbled-ice as thick as the grit on 40-grit sandpaper had formed on the upper wings…

obviously, engineered to require laminar, there, but having turbulent, cost all those lives.

iirc, it was Arvel Gentry, or “Principles of Yacht Design”, that stated it takes a ridge of about 0.1mm, only, to trip the flow around a mast from laminar to turbulent…

Given how barnacles & such are generally 100x or more as thick as that, when removed from a hull, I think laminar-flow is something that exists only for the 1st day or so after launching!

I now want to see experiment showing polar curves for rudders coated normally, uncoated, & ailicone-silane coated, to see if it is the coating that induces separation-bubbles, or if it is AoA exceeding functional angle, for that surface & foil,, while the boundary-layer is in specifically turbulent flow, as opposed to the ideal laminar, as aviation’s results indicate…

just an amateur student of naval-architecture & aircraft-design ( Daniel P. Raymer’s “Conceptual Aircraft Design” is *brilliant*, btw ), who happens to study this stuff autistically, as that is the only way to make my designs become absolutely-competent, is all…

I got a pearson and the rudder broke. Can I just replace with a outboard rudder mount it off set for room for outboard need info.

You could but it will not work very well. How badly it would perform is difficult to say. It might be just poor or disastrous. Things really need to be balanced on sail boats.

Polished rudders stall at low angles of attack and ask any hobie cat racer.

Pi is NOT 3.146

3.1416 maybe

Yup, 3.1416. Typo.

Before 2005 , when I fully retired and went cruising 10 months per year, I changed auto pilots, the hydraulics of which reduced the maximum rudder angle. “Someday” had always been difficult to steer in marinas, so I added 30% more rudder area to the Gulfstar 41′ by deepening and following the existing angles. (the pivot was unchanged, as all added area was aft of that.) It increased rudder effort noticeably, but not excessively, improved motor maneauvering and allowed being able to hold a close line better. Noticeably, it caused a lot more stalling of the rudder whenever it was turned very much. A recent tangle with a Guatemala fish net damaged the extension, which I had intended to be sacrificial. I cleaned up the separation somewhat, but have not replaced the extension. The boat again now requires more steering correction when heading at all upwind, but the rudder does not stall as easily.

This is not a scientific study, just my personal non-scientific observations. The added rudder area was quite low, and the fairing quality was…well! modest.

I’ve seen data suggesting ~ 400 grit is best, and I’ve seen data suggesting polished is best. They were both smart, respected guys that I would not second guess. My conclusion is that other factors, such as the specific foil profile and the type of coating, are involved. Let’s just agree that many layers of rolled bottom paint with a few lumps and chips is sub-optimal! We’re talking about cruising boats.

Thanks for great article. I’m convinced enough to go sand my bottom paint off the lifting rudder of my Dragonfly Tri.

Absolutely! No lifting rudder should have bottom paint. My Farrier rudder was sanded fair and painted with gloss white.

Dagger boards and center boards that retract still need antifouling, since they do not lift clear of the water, but because they are in a confined space with little oxygen or water flow, fouling is very limited. Because the space is tight and paint build-up can cause jamming, sand well and limit the number of coats. For my center board I go with two coats on the leading edge (exposed even when lifted) and one coat on the rest.

I do remember a comment directed to cruisers a few years back suggesting that a faster cruiser would be more likely to get out of the way of dirty weather, especially with modern forecasting. I reckoned that this concept would gain traction, but I haven’t seen it. Can anyone weigh in on this opinion?

As interesting as the article reads, I wonder how it helps a prospective buyer of a used boat. Pictures will not do, and neither will taking several boats out of the water to examine them; it’s too expensive. It would be more helpful to indicate which boat manufacturers have the type of rudder the author recommends. After all, the buyer usually cannot be expected to change a rudder prior to buying it; it is also expensive. By the way, these types of very sophisticated articles are seen when it comes to hulls, keels, or rigging but without identifying the boats that carry the wrong equipment. If a specific rudder or keel configuration is not the proper one for efficient sailing, the author ought to state which boats carry the proper ones so that the buyer will concentrate on the whole (the boat) rather than the part.

I was describing the opportunity to improve the existing rudder. As I think back, I have modified the rudder of every boat I have owned in order to improve efficiency. The first two got small changes in balance and improved trailing edge sharpness. On the third I tightened the the hull clearance and changed the section. On my current boat I adding an anti-ventilation fence to improve high speed handling. https://4.bp.blogspot.com/-2ZGPzKdj_tE/WyF9G2mHtLI/AAAAAAAAOwE/r6zgQEr4vkcDB4ciMLcgboFdazDAseDBgCLcBGAs/s1600/ian%2Brudder%2Bfence.jpg None of these tasks was overly difficult, and none was undertaken until I had sailed the boat for a season and learned what balance she liked and noted her habits.

For me, I buy a boat based on reputation, a test sail, and in most cases, a survey. As you imply, it is the whole boat you are buying. Does it have good bones? Do you feel happy at the helm? Then comes the fine tuning. I’ve been told that I sell a boat when I run out of things to tweak.

wow, so now case reports/medical reports/evidence don’t count as “evidence”, but certain remedies, even if they are cited in medical journals but do not work in the real world, count as evidence to you?? Maybe we need to redefine evidence based on your philosophies.Anyway, i’ve wasted enough time here. goodbye.

Weight 2.5 tonnes

Do you have any articles on the ideal cross section shape for an outboard rudder mounted 50mm from the transom vertically The yacht is a 26 ft trailer sailer weight 2.5 tonnes

The most common choice would be NACA 0012. http://airfoiltools.com/airfoil/details?airfoil=n0012-il

There are many ways to build a rudder, including laminated solid rot-resistant wood and fiber glass covered foam with a metal armature core. For the DIY, laminated wood is probably the most practical.

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Log in to leave a comment

Latest Videos

Island Packet 370: What You Should Know | Boat Review

How To Make Starlink Better On Your Boat | Interview

Catalina 380: What You Should Know | Boat Review

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

- Paddle Board

What Is a Sailboat Rudder? An Overview of Its Function and Design

Sailboats have been used for thousands of years to traverse water. They have undergone many changes and improvements over the years, and one of the essential components of a sailboat is the rudder.

Quick Facts

Understanding the sailboat rudder.

The rudder is a vital component of a sailboat that plays a crucial role in steering and maneuvering the vessel. The rudder works by changing the direction of the water flow around it, which moves the boat in the opposite direction. Without a rudder, it would be impossible to navigate a sailboat effectively, especially in different water and wind conditions.

Components of a Sailboat Rudder

A sailboat rudder comprises several components, each with a unique function that contributes to the rudder’s overall effectiveness. The stock is the main vertical shaft that connects the rudder blade to the boat’s helm. It is usually made of stainless steel or aluminum alloy and is designed to withstand the forces exerted on the rudder during navigation.

The blade is the flat portion of the rudder that faces the water current and directs the water flow in the opposite direction to steer the boat. The blade is typically made of fiberglass-reinforced plastic or aluminum alloy and is designed to be lightweight and durable. Pintles and gudgeons are the two connections between the rudder and stern that allow for easy installation and removal of the rudder. Pintles are the vertical metal pins that fit into the gudgeons, which are the horizontal metal brackets attached to the boat’s stern.

Different Types of Rudders

There are several types of rudders used in sailboats, each with its advantages and disadvantages. Transom-mounted rudders are the most common type of rudder, and they are mounted on the stern of the boat. Skeg-mounted rudders are attached to a fixed fin called a skeg, which provides additional stability to the rudder.

Keel-mounted rudders are attached to the boat’s keel, which is the central structural element that runs along the bottom of the hull. Spade rudders are free-standing rudders that are not attached to any part of the boat and are commonly used in racing sailboats. The type of rudder used depends on the boat’s size, design, and intended use.

Materials Used in Rudder Construction

Rudders can be made from various materials, each with its advantages and disadvantages. Wooden rudders are the traditional choice and are still used in some sailboats today. However, they are relatively heavy and require regular maintenance to prevent rot and decay.

Aluminum alloy rudders are lightweight and durable, making them an excellent choice for racing sailboats. Stainless steel rudders are also durable but are heavier than aluminum alloy rudders. Fiberglass-reinforced plastic rudders are the most common type of rudder used today, as they are lightweight, durable, and require minimal maintenance.

The sailboat rudder is an essential component that plays a crucial role in steering and maneuvering a sailboat. Understanding the different types of rudders, their components, and the materials used in their construction can help sailors choose the right rudder for their boat and navigate more effectively in different water and wind conditions.

The Function of a Sailboat Rudder

Steering and maneuvering.

The primary function of a sailboat rudder is to steer and maneuver the boat. The rudder’s blade directing the flow of water in a specific direction allows for the steering of the boat as the blade changes direction. Sailors can use the rudder to turn the boat in any direction they choose, allowing them to navigate through narrow channels or around obstacles in the water. It is essential to note that the rudder works in conjunction with the sails to control the boat’s direction and speed.

Balancing the Sailboat

The balance of the sailboat is critical to ensure safe maneuvering, and the rudder plays a crucial role in achieving this. A balanced rudder helps in keeping the boat steady, reducing drag, and preventing unwanted turning. Sailors can adjust the rudder’s angle to keep the boat balanced and on course, especially in rough water conditions. A well-balanced rudder also helps to reduce the risk of capsizing or losing control of the boat .

Rudder Effectiveness in Different Conditions

Rudder effectiveness varies depending on the boat’s size, weight, and water and wind conditions. A larger boat may require a bigger rudder for proper maneuvering, while a smaller boat can work with a smaller rudder. Sailors must also consider the water and wind conditions when choosing the right rudder for their boat. In calm waters, a smaller rudder may be sufficient, but in rough water, a larger rudder may be necessary to maintain control of the boat. Additionally, the rudder’s effectiveness can be affected by the boat’s speed, with higher speeds requiring more significant rudders to maintain control.

It is also important to note that the rudder’s effectiveness can be impacted by external factors such as weeds or debris in the water. These factors can reduce the rudder’s ability to steer the boat and require sailors to make adjustments to maintain control. Additionally, the rudder’s effectiveness can be impacted by the sailor’s skill level, with more experienced sailors able to make more precise adjustments to the rudder to control the boat’s direction and speed.

Design Considerations for Sailboat Rudders

Sailboat rudders are an essential component of a boat’s steering and maneuvering system. A well-designed rudder can make all the difference in a boat’s performance , especially in challenging weather conditions. In this article, we will explore some of the key design considerations for sailboat rudders.

Rudder Size and Shape

The size and shape of a rudder play a crucial role in determining its effectiveness in steering and maneuvering a boat. A larger rudder provides more leverage and maneuverability, allowing the boat to turn more sharply. However, a larger rudder may also produce more drag, which can slow down the boat’s speed.

The shape of the rudder is also important. A well-designed rudder should be streamlined to reduce drag and turbulence. The thickness of the rudder should be carefully considered to ensure that it is strong enough to withstand the forces exerted on it while remaining lightweight.

Rudder Placement and Configuration

The placement of the rudder on the boat can significantly affect its performance. A rudder that is too far forward can cause the boat to become unstable, while a rudder that is too far aft can make it difficult to steer. The location of the rudder must also take into account factors such as the propeller’s placement and the boat’s shape.

The configuration of the rudder can also determine its effectiveness and balance. A single rudder is the most common configuration, but some boats have twin rudders to provide more steering control. The angle of the rudder blade can also be adjusted to optimize its performance.

Hydrodynamic and Aerodynamic Factors

The design of a rudder must take into consideration the hydrodynamic and aerodynamic factors affecting the boat’s performance. Hydrodynamic factors include water flow, pressure, and turbulence, which can significantly affect the rudder’s performance. The shape and placement of the rudder must be carefully designed to minimize these effects.

Aerodynamic factors consider the wind and air resistance’s impact on the boat’s performance. The rudder’s size and shape must be designed to minimize the wind’s effect on the boat while providing sufficient steering control.

The design of a sailboat rudder is a complex process that requires careful consideration of many factors. The size and shape of the rudder, its placement on the boat, and its configuration must be optimized to provide effective steering and maneuverability. By taking into account the hydrodynamic and aerodynamic factors affecting the boat’s performance, a well-designed rudder can significantly improve a sailboat’s overall performance.

Rudder Maintenance and Repair

The rudder is a crucial component of any sailboat, providing steering and control. As such, it’s essential to keep it in good working order through regular maintenance and inspections.

Inspecting Your Rudder

Regular inspection of the rudder is essential to ensure its continued performance and longevity. A thorough inspection includes checking for cracks, wear and tear, and loose components such as hinges, pins, and screws. It’s also important to check the rudder’s alignment and ensure it moves smoothly and without any obstructions.

During your inspection, be sure to check for signs of corrosion, particularly on metal components. Corrosion can weaken the rudder and cause it to fail, so regular cleaning and maintenance are essential to prevent this.

If you notice any issues during your inspection, it’s important to address them promptly. Small cracks or damage can often be repaired, but if the damage is extensive, it may be necessary to replace the rudder entirely.

Common Rudder Issues and Solutions

One common issue with rudders is corrosion, particularly on metal components. Regular cleaning and maintenance help prevent corrosion and ensure the rudder’s longevity. If you do notice signs of corrosion, it’s important to address it promptly to prevent further damage.

Another common issue is damage to the blade or stock. This can be caused by impact with debris or other boats, or simply wear and tear over time. If the damage is minor, it may be possible to repair the rudder. However, if the damage is extensive or compromises the rudder’s structural integrity, it may be necessary to replace it entirely.

Loose components such as hinges, pins, and screws can also cause issues with the rudder. These should be checked regularly and tightened or replaced as needed.

When to Replace or Upgrade Your Rudder

Sailboat rudders can last for many years, but at some point, replacement or upgrade may be necessary. This includes upgrading to a newer design or larger rudder to improve the boat’s performance or replacing a damaged or worn-out rudder that is beyond repair.

If you’re considering upgrading your rudder, it’s important to consult with a professional to ensure that the new rudder is compatible with your boat and will provide the desired performance improvements.

Regular maintenance and inspections are essential to ensure the continued performance and longevity of your sailboat’s rudder. By staying on top of any issues and addressing them promptly, you can ensure that your rudder will continue to provide reliable steering and control for many years to come.

A sailboat’s rudder is a crucial component that helps steer and maneuver the boat safely. The size, shape, placement, and construction materials must all be taken into consideration when designing or replacing a rudder. Regular maintenance and inspection help ensure its continued performance and longevity.

Rudder FAQS

How does a sailboat rudder work.

A sailboat rudder works by changing the direction of the water flow past the boat’s hull, which in turn changes the direction of the boat. The rudder is attached to the stern of the boat and can be turned left or right. When the rudder is turned, it creates a force that pushes the stern in the opposite direction and turns the bow towards the direction the rudder is turned. This is how a rudder steers a boat.

What is a rudder and its purpose?

A rudder is a flat piece, usually made of metal or wood, attached to the stern of a vessel such as a boat or ship. The main purpose of the rudder is to control the direction of the vessel. It does this by deflecting water flow, creating a force that turns the vessel. Without a rudder, steering a vessel would be significantly more challenging.

Can you steer a sailboat without a rudder?

Steering a sailboat without a rudder is challenging but not impossible. Sailors can use the sails and the keel to influence the direction of the boat. By trimming the sails and shifting weight, it’s possible to cause the boat to turn. However, this is a difficult technique that requires a deep understanding of sailing dynamics and is usually considered a last resort if the rudder fails.

What controls the rudder on a sailboat?

The rudder on a sailboat is typically controlled by a steering mechanism, like a tiller or a wheel. The tiller is a lever that is directly connected to the top of the rudder post. Pushing the tiller to one side causes the rudder to turn to the opposite side. On larger boats, a wheel is often used. The wheel is connected to the rudder through a series of cables, pulleys, or hydraulic systems, which turn the rudder as the wheel is turned.

How do you steer a sailboat with a rudder?

To steer a sailboat with a rudder, you use the tiller or wheel. If your sailboat has a tiller, you’ll push it in the opposite direction of where you want to go – pushing the tiller to the right will turn the boat to the left and vice versa. If your sailboat has a wheel, it operates like a car steering wheel – turning it to the right steers the boat to the right and turning it to the left steers the boat to the left.

How do you steer a sailboat against the wind?

Steering a sailboat against the wind, also known as tacking, involves a maneuver where the bow of the boat is turned through the wind. Initially, the sails are let out, and then the boat is steered so that the wind comes from the opposite side. As the boat turns, the sails are rapidly pulled in and filled with wind from the new direction. This maneuver allows the boat to zigzag its way upwind, a technique known as “beating.” It requires skill and understanding of sailing dynamics to execute effectively.

John is an experienced journalist and veteran boater. He heads up the content team at BoatingBeast and aims to share his many years experience of the marine world with our readers.

What to Do If Your Boat Engine Won’t Start? Common Problems & How to Fix Them

How to launch a boat by yourself: complete beginner’s guide, how to surf: complete beginner’s guide to get you started.

Comments are closed.

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

- Types of Sailboats

- Parts of a Sailboat

- Cruising Boats

- Small Sailboats

- Design Basics

- Sailboats under 30'

- Sailboats 30'-35

- Sailboats 35'-40'

- Sailboats 40'-45'

- Sailboats 45'-50'

- Sailboats 50'-55'

- Sailboats over 55'

- Masts & Spars

- Knots, Bends & Hitches

- The 12v Energy Equation

- Electronics & Instrumentation

- Build Your Own Boat

- Buying a Used Boat

- Choosing Accessories

- Living on a Boat

- Cruising Offshore

- Sailing in the Caribbean

- Anchoring Skills

- Sailing Authors & Their Writings

- Mary's Journal

- Nautical Terms

- Cruising Sailboats for Sale

- List your Boat for Sale Here!

- Used Sailing Equipment for Sale

- Sell Your Unwanted Gear

- Sailing eBooks: Download them here!

- Your Sailboats

- Your Sailing Stories

- Your Fishing Stories

- Advertising

- What's New?

- Chartering a Sailboat

- Sailboat Rudder

Making a Sailboat Rudder for s/y Alacazam

It's not enough just for a sailboat rudder to steer the boat effectively, it should also contribute to the keel's job of providing lift to windward, and for it to do this it must be designed as a hydrodynamic foil.

Of course a rudder doesn't have to provide lift, but it's a wasted opportunity if it doesn't.

As with an aircraft's wing, to develop lift the sailboat rudder must have water flowing over its leading edge at an angle of attack.

Fortunately for us sailors, the pressure of air on the windward side of the sails, pushes the boat bodily off course slightly and it's this leeway that provide the angle of attack - or angle of incidence- that enables our keels and rudders to provide lift.

But What Type of Sailboat Rudder would be Best for Alacazam ?

First, we considered twin transom-mounted rudders. The usual argument for twin rudders is:

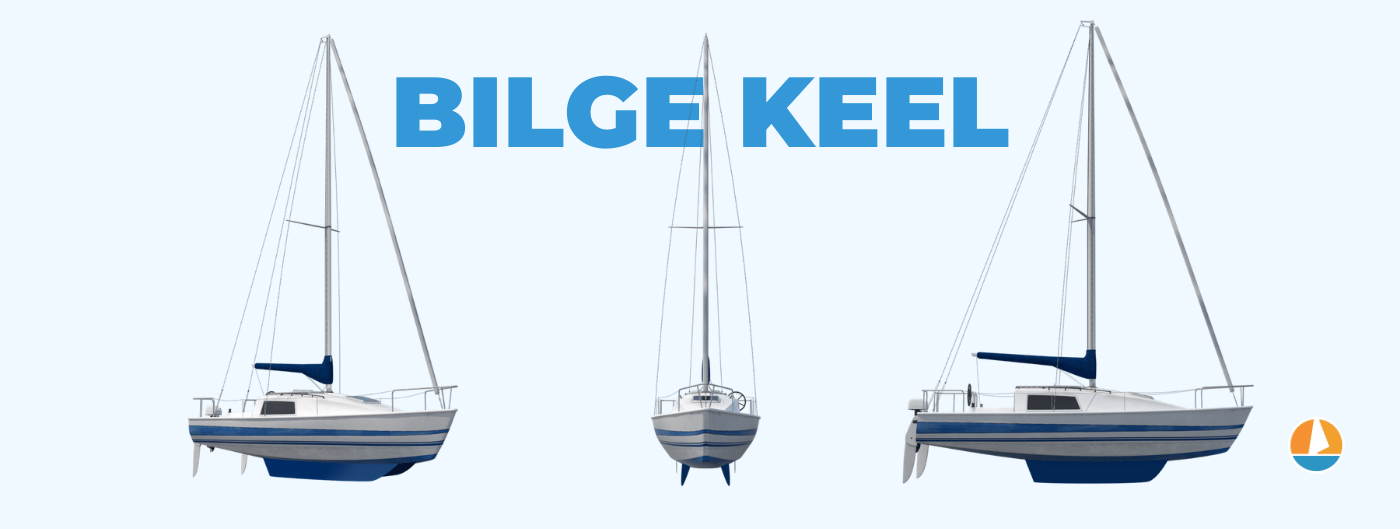

- as the boat heels, the leeward rudder is more deeply immersed and provides better control, and

- the boat, resting on the keel and two rudders can dry-out upright.

But in the end we decided against the twin rudder arrangement because:~

- with Alacazam's deep draught (7 feet, or 2.2m) the twin rudders wouldn't be deep enough to achieve the drying-out upright benefit, and

- the mechanical complexity of tiller steered twin rudder system went against one of our key design principles - keep it simple, and

- with no propwash flowing over the rudders, manoeuvring under power in tight situations would be a little too interesting for my tastes.

So the conventional single rudder approach it was to be. But what type of sailboat rudder?

A Transom-Hung Rudder

We liked the simplicity of this arrangement, but it didn't suit Alacazam's hull design at the stern. We wanted a sugar-scoop design with a bathing platform to allow easy access from the dinghy which ruled out a transom hung rudder. Similarly, it meant that mounting the servo-pendulum self-steering gear would be unnecessarily complicated.

Spade Rudder

The spade rudder is the most efficient of all sailboat rudders, which is why you're unlikely to see any other design on racing yachts.

The absence of a skeg means that all of its area is used to apply a turning force to the hull, minimizing wetted area and associated drag.

The area ahead of the stock helps to balance the rudder, making life easier for the helmsman.

But it's not the most robust design, being entirely dependent on the strength of rudder stock to resist impact damage.

Theoretically it's just a matter of engineering, but high performance spade rudders just aren't thick enough to incorporate a rudder stock of sufficient diameter for ultimate security.

Skeg-Hung Rudder

Other than those rudders hung on the following edge of long keels, the skeg hung rudder - supported top and bottom on a full length skeg - is the most robust design.

Without a portion forward of the stock, there's no balancing force to take the load of the helmsman's arms - so loads can be quite heavy in some designs.

Nevertheless, it's a very popular design for offshore cruising boats.

Semi-Balanced Rudder

This design of sailboat rudder is something of a compromise between the spade rudder and the full skeg rudder.

Supported at its mid-point by a half-depth skeg, it benefits by the area forward of the stock, below the skeg.

This applies a balancing force as the rudder is turned making the steering lighter than it would otherwise be. And it was this design we chose for Alacazam's rudder.

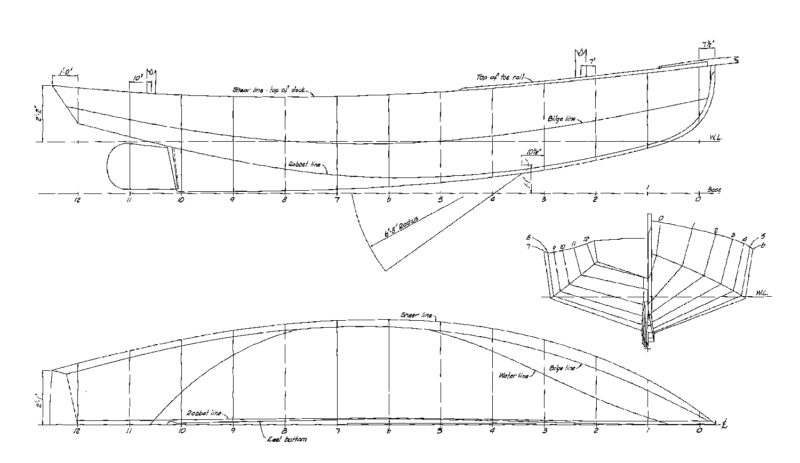

Making Alacazam's Rudder

A typical productions boat's rudder is likely to have been fabricated as shown here, with two GRP mouldings 'clamshelled' around a foam core.

Not the most reliable arrangement you might think - and you'd be right.

We wanted something a little more robust for Alacazam's rudder.

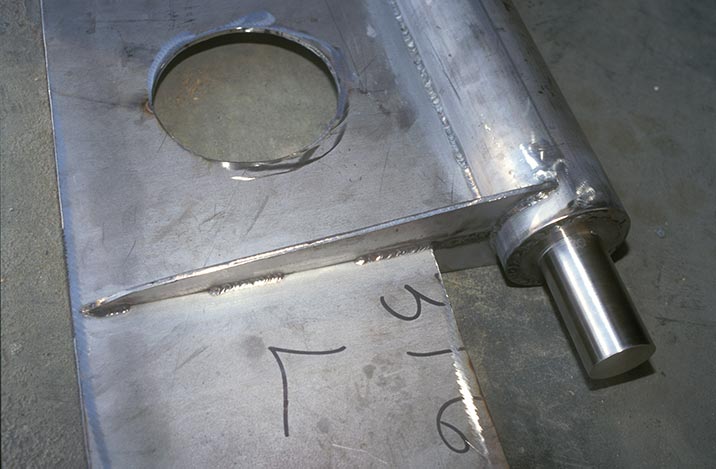

But first, the rudder stock.

We fabricated this from a 2" (50mm) diameter stainless steel solid bar and welded on flat stainless tangs that would be embedded within the rudder.

The Admiralty Bronze casting will eventually connect the rudder to the skeg.

With the rudder stock fabricated, we began the construction of the rudder core.

It was made up from half inch (12mm) marine ply sheets, cut to shape and incorporating cut-outs for the tangs, screwed and glued together.

The rudder and skeg was built up as a single unit at this stage.

The rudder design software generated coordinates for various stations along the rudder, and we used these to cut templates so that we could get the shape right.

Shaping the rudder profile was done by hand, initially with a plane to remove the excess, then with a file and diminishingly coarse grades of sandpaper.

Once the rudder profile matched the appropriate template we removed the section that would form the skeg.

Next, the rudder was fitted to the stock with any gaps between the tangs and the ply taken up with high-strength epoxy 'gloop'.

Finally both the rudder and the skeg were sheathed in several layers of epoxy-glass rovings before being filled and faired with epoxy fairing compound.

Fitting the Sailboat Rudder

The skeg was letter-boxed through a slot cut in the hull, securely braced internally and bonded to it with fillets of high-strength epoxy and epoxy glass rovings.

Inside the hull we had constructed a GRP tube to contain the stock, and the skeg was also bonded to the lower end of that.

The rudder was then securely fitted to the stock via the bronze bearing, and located at the top of the rudder by a stainless steel bearing.

That's it, we now have a very robust and efficient rudder securely attached to Alacazam's hull.

Recent Articles

'Natalya', a Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 54DS for Sale

Mar 17, 24 04:07 PM

'Wahoo', a Hunter Passage 42 for Sale

Mar 17, 24 08:13 AM

Used Sailing Equipment For Sale

Feb 28, 24 05:58 AM

Here's where to:

- Find Used Sailboats for Sale...

- Find Used Sailing Gear for Sale...

- List your Sailboat for Sale...

- List your Used Sailing Gear...

Building Alacazam...

But why go to the bother of building your own boat?

Copyright © 2024 Dick McClary Sailboat-Cruising.com

My Cruiser Life Magazine

All About the Rudder on a Sailboat

The rudder on a sailboat is one of those important parts that often gets overlooked. It’s hidden underwater most of the time and usually performs as expected when we ask something of it.

But when was the last time you seriously considered your sailboat rudder? Do you have a plan if it fails? Here’s a look at various designs of sail rudder, along with the basics of how it works and why it’s there.

Table of Contents

How are sailboat rudders different than keels, how does the rudder work, wheel steering vs. tiller steering, full keel rudder sailboat, skeg-hung rudders, spade rudder, variations on designs, emergency outboard rudder options, looking to sail into the sunset grab the wheel, steer your sail boat rudder, and get out there, sail boat rudder faqs.

What Is a Boat Rudder?

The rudder is the underwater part of the boat that helps it turn and change direction. It’s mounted on the rear of the boat. When the wheel or tiller in the cockpit is turned, the rudder moves to one side or another. That, in turn, moves the boat’s bow left or right.

When it comes to sailing, rudders also offer a counterbalance to the underwater resistance caused by the keel. This enables the boat to sail in a straight line instead of just spinning around the keel.

Sailboat hull designs vary widely when you view them out of the water. But while the actual shape and sizes change, they all have two underwater features that enable them to sail–a rudder and a keel.

The rudder is mounted at the back of the boat and controls the boat’s heading or direction as indicated by the compass .

The keel is mounted around the center of the boat. Its job is to provide a counterbalance to the sails. In other words, as the wind presses on the sails, the weight of the ballast in the keel and the water pressure on the sides of the keel keeps the boat upright and stable.

When sailing, the keel makes a dynamic force as water moves over it. This force counters the leeway made by air pressure on the sails and enables the boat to sail windward instead of only blowing downwind like a leaf on the surface.

The rudder is a fundamental feature of all boats. Early sailing vessels used a simple steering oar to get the job done. Over the years, this morphed into the rudder we know today.

However, thinking about a rudder in terms of a steering oar is still useful in understanding its operation. All it is is an underwater panel that the helmsperson can control. You can maintain a course by trailing the oar behind the boat while sailing. You can also change the boat’s heading by moving it to one side or the other.

The rudders on modern sailboats are a little slicker than simple oars, of course. They are permanently mounted and designed for maximum effectiveness and efficiency.

But their operating principle is much the same. Rudders work by controlling the way water that flows over them. When they move to one side, the water’s flow rate increases on the side opposite the turn. This faster water makes less pressure and results in a lifting force. That pulls the stern in the direction opposite the turn, moving the bow into the turn.

Nearly all boats have a rudder that works exactly the same. From 1,000-foot-long oil tankers to tiny 8-foot sailing dinghies, a rudder is a rudder. The only boats that don’t need one are powered by oars or have an engine whose thrust serves the same purpose, as is the case with an outboard motor.

Operating the Rudder on a Sailboat

Rudders are operated in one of two ways–with a wheel or a tiller. The position where the rudder is operated is called the helm of a boat .

Ever wonder, “ What is the steering wheel called on a boat ?” Boat wheels come in all shapes and sizes, but they work a lot like the wheel in an automobile. Turn it one way, and the boat turns that way by turning the rudder.

A mechanically simpler method is the tiller. You’ll find tiller steering on small sailboats and dinghies. Some small outboard powerboats also have tiller steering. Instead of a wheel, the tiller is a long pole extending forward from the rudder shaft’s top. The helmsperson moves the tiller to the port or starboard, and the bow moves in the opposite direction. It sounds much more complicated on paper than it is in reality.

Even large sailboats will often be equipped with an emergency tiller. It can be attached quickly to the rudder shaft if any of the fancy linkages that make the wheel work should fail.

Various Sail Boat Rudder Designs

Now, let’s look at the various types of rudders you might see if you took a virtual walk around a boatyard. Since rudders are mostly underwater on the boat’s hull, it’s impossible to compare designs when boats are in the water.

Keep in mind that these rudders work the same way and achieve the same results. Designs may have their pluses and minuses, but from the point of view of the helmsperson, the differences are negligible. The overall controllability and stability of the boat are designed from many factors, and the type of rudder it has is only one of those.

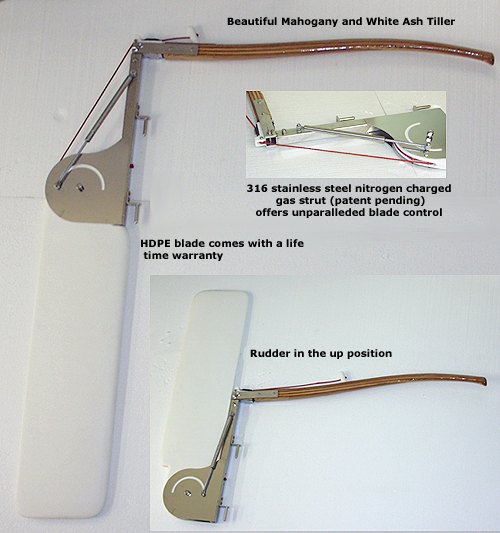

You’ll notice that rudder design is closely tied to keel design. These two underwater features work together to give the boat the sailing characteristics the designer intended.

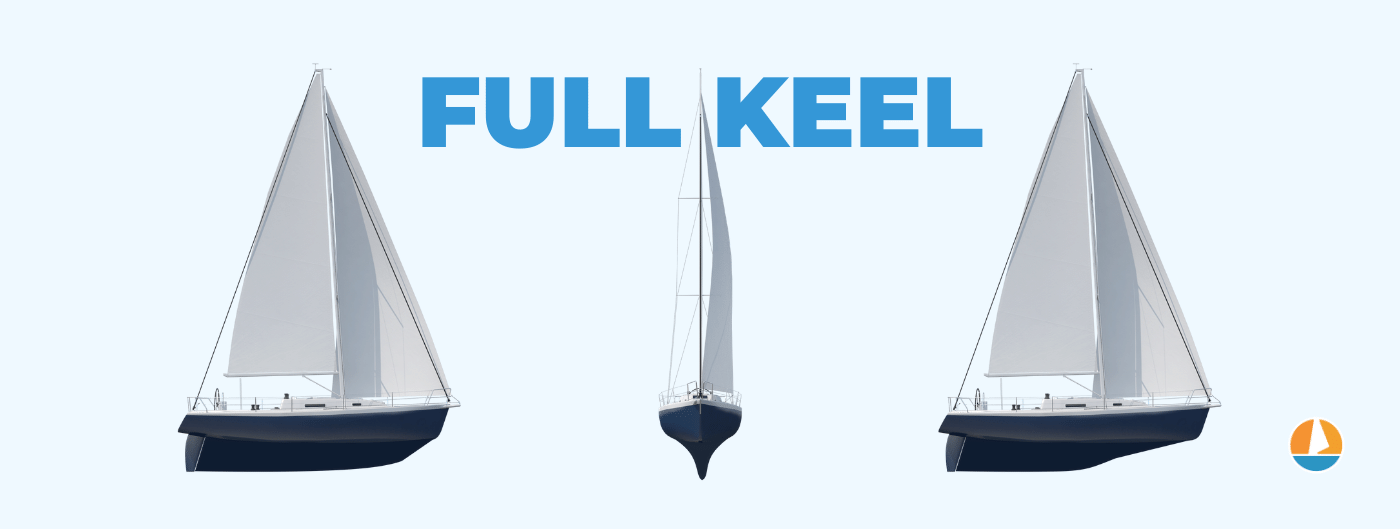

The classic, robust offshore sailboat is designed with a full keel that runs from stem to stern. With this sort of underwater profile, it only makes sense that the rudder would be attached to the trailing edge of that enormous keel. On inboard-powered sailboats, the propeller is usually mounted inside an opening called the aperture between the keel and rudder.

The advantages of this design are simplicity and robustness. The keel is integrated into the hull and protects the rudder’s entire length. Beyond reversing into an obstacle, anything the boat might strike would hit the keel first and would be highly unlikely to damage the rudder. Not only does the keel protect it, but it also provides a very strong connection point for it to be attached to.

Full keel boats are known for being slow, although there are modern derivatives of these designs that have no slow pokes. Their rudders are often large and effective. They may not be the most efficient design, but they are safe and full keels ride more comfortably offshore than fin-keeled boats.

Plenty of stout offshore designs sport full keel rudders. The Westsail 38s, Lord Nelsons, Cape Georges, Bristol/Falmouth Cutters, or Tayana 37s feature a full keel design.

A modified full keel, like one with a cutaway forefoot, also has a full keel-style rudder. These are more common on newer designs, like the Albergs, Bristols, Cape Dorys, Cabo Ricos, Island Packets, or the older Hallberg-Rassys.

A design progression was made from full keel boats to long-fin keelboats, and the rudder design changed with it. Designers used a skeg as the rudder became more isolated from the keel. The skeg is a fixed structure from which you can mount the rudder. This enables the rudder to look and function like a full keel rudder but is separated from the keel for better performance.

The skeg-hung rudder has a few of the same benefits as a full keel rudder. It is protected well and designed robustly. But, the cutaways in the keel provide a reduced wetted surface area and less drag underwater, resulting in improved sailing performance overall.

Larger boats featuring skeg-mounted rudders include the Valiant 40, Pacific Seacraft 34, 37, and 40, newer Hallberg-Rassys, Amels, or the Passport 40.

It’s worth noting that not all skegs protect the entire rudder. A partial skeg extends approximately half the rudder’s length, allowing designers to make a balanced rudder.

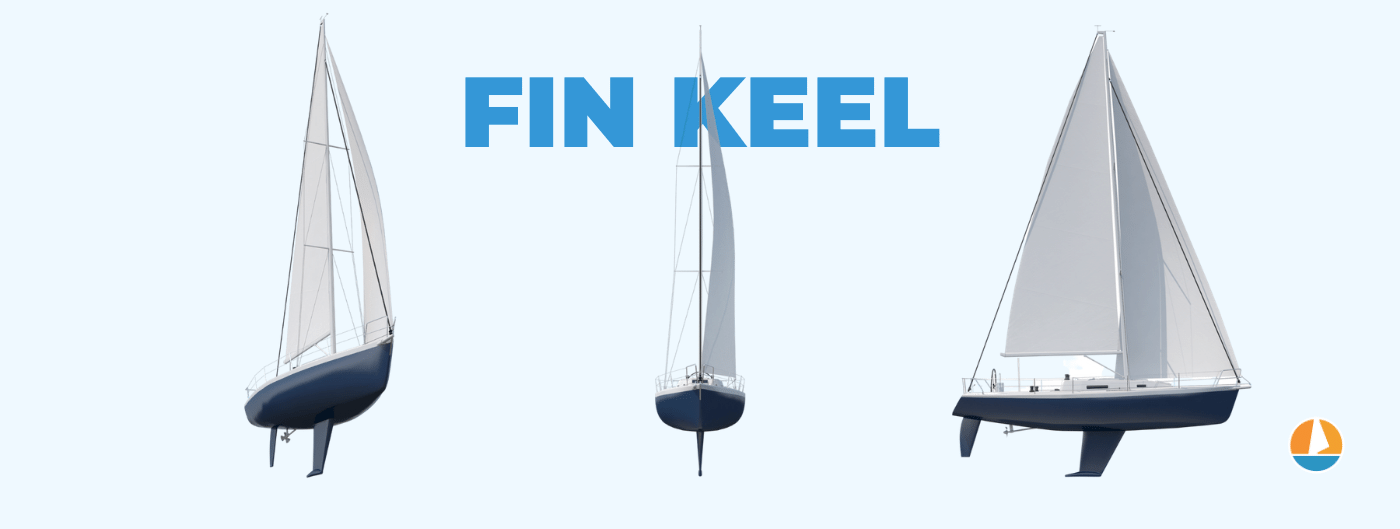

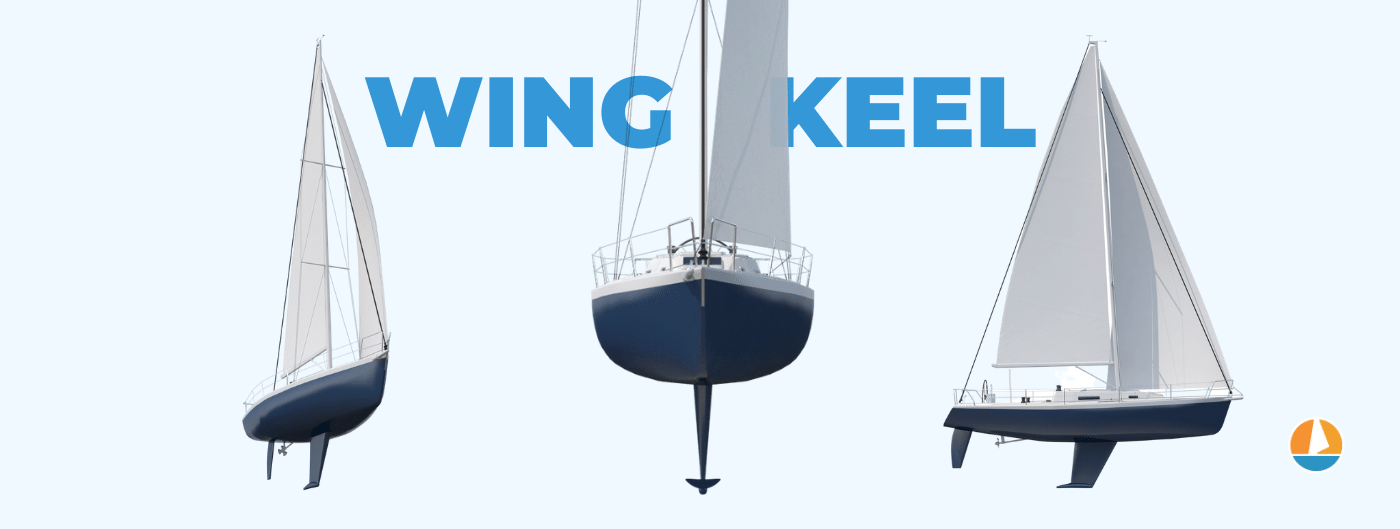

With higher-performance designs, keels have become smaller and thinner. Fin keel boats use more hydrodynamic forces instead of underwater area to counter the sail’s pressure. With the increased performance, skegs have gone the way of the dinosaurs. Nowadays, rudders are sleek, high aspect ratio spade designs that make very little drag. They can be combined with a number of different keel types, including fin, wing keels , swing keels, or bulb keels.

The common argument made against spade rudders is that they are connected to the boat by only the rudder shaft. As a result, an underwater collision can easily bend the shaft or render the rudder unusable. In addition, these rudders put a high load on the steering components, like the bearings, which are also more prone to failure than skeg or full keel designs. For these reasons, long-distance cruisers have traditionally chosen more robust designs for the best bluewater cruising sailboats .

But, on the other hand, spade rudders are very efficient. They turn the boat quickly and easily while contributing little to drag underwater.

Spade rudders are common now on any boat known for performance. All racing boats have a spade rudder, like most production boats used for club racing. Pick any modern fin keel boat from Beneteau, Jeanneau, Catalina, or Hunter, and you will find a spade rudder. Spade rudders are common on all modern cruising catamarans, from the Geminis to the Lagoons, Leopards, and Fountaine Pajots favored by cruisers and charter companies.

Here are two alternative designs you might see out on the water.

Transom-Hung or Outboard Rudders

An outboard rudder is hung off the boat’s transom and visible while the boat is in the water. Most often, this design is controlled by a tiller. They are common on small sailing dingies, where the rudder and tiller are removable for storage and transport. The rudder is mounted with a set of hardware called the pintle and gudgeon.

Most outboard rudders are found on small daysailers and dinghies. There are a few classic big-boat designs that feature a transom-hung rudder, however. For example, the Westsail 38, Alajuela, Bristol/Falmouth Cutters, Cape George 36, and some smaller Pacific Seacrafts (Dana, Flicka) have outboard rudders.

Twin Sailing Rudder Designs

A modern twist that is becoming more common on spade rudder boats is the twin sailboat rudder. Twin rudders feature two separate spade rudders mounted in a vee-shaped arrangement. So instead of having one rudder pointed down, each rudder is mounted at an angle.

Like many things that trickle down to cruising boats, the twin rudder came from high-performance racing boats. By mounting the rudders at an angle, they are more directly aligned in the water’s flow when the boat is healed over for sailing. Plus, two rudders provide some redundancy should one have a problem. The twin rudder design is favored by designers looking to make wide transom boats.

There are other, less obvious benefits of twin rudders as well. These designs are easier to control when maneuvering in reverse. They are also used on boats that can be “dried out” or left standing on their keel at low tide. These boats typically combine the twin rudders with a swing keel, like Southerly or Sirius Yachts do. Finally, twin rudders provide much better control on fast-sailing hulls when surfing downwind.

Unbalanced vs. Balanced Rudders

Rudders can be designed to be unbalanced or balanced. The difference is all in how they feel at the helm. The rudder on a bigger boat can experience a tremendous amount of force. That makes turning the wheel or tiller a big job and puts a lot of strain on the helmsperson and all of the steering components.

A balanced rudder is designed to minimize these effects and make turning easier. To accomplish this, the rudder post is mounted slightly aft of the rudder’s forward edge. As a result, when it turns, a portion of the leading edge of the rudder protrudes on the opposite side of the centerline. Water pressure on that side then helps move the rudder.

Balanced rudders are most common in spade or semi-skeg rudders.

Sail Rudder Failures

Obviously, the rudder is a pretty important part of a sailboat. Without it, the boat cannot counter the forces put into the sails and cannot steer in a straight line. It also cannot control its direction, even under power.

A rudder failure of any kind is a serious emergency at sea. Should the rudder be lost–post and all–there’s a real possibility of sinking. But assuming the leak can be stopped, coming up with a makeshift rudder is the only way you’ll be able to continue to a safe port.

Rudder preventative maintenance is some of the most important maintenance an owner can do. This includes basic things that can be done regularly, like checking for frayed wires or loose bolts in the steering linkage system. It also requires occasionally hauling the boat out of the water to inspect the rudder bearings and fiberglass structure.

Many serious offshore cruisers install systems that can work as an emergency rudder in extreme circumstances. For example, the Hydrovane wind vane system can be used as an emergency rudder. Many other wind vane systems have similar abilities. This is one reason why these systems are so popular with long-distance cruisers.

There are also many ways to jury rig a rudder. Sea stories abound with makeshift rudders from cabinet doors or chopped-up sails. Sail Magazine featured a few great ideas for rigging emergency rudders .

Understanding your sail rudder and its limitations is important in planning for serious cruising. Every experienced sailor will tell you the trick to having a good passage is anticipating problems you might have before you have them. That way, you can be prepared, take preventative measures, and hopefully never deal with those issues on the water.

What is the rudder on a sailboat?

The rudder is an underwater component that both helps the sailboat steer in a straight line when sailing and turn left or right when needed.

What is the difference between a rudder and a keel?

The rudder and the keel are parts of a sailboat mounted underwater on the hull. The rudder is used to turn the boat left or right, while the keel is fixed in place and counters the effects of the wind on the sails.

What is a rudder used for on a boat?

The rudder is the part of the boat that turns it left or right

Matt has been boating around Florida for over 25 years in everything from small powerboats to large cruising catamarans. He currently lives aboard a 38-foot Cabo Rico sailboat with his wife Lucy and adventure dog Chelsea. Together, they cruise between winters in The Bahamas and summers in the Chesapeake Bay.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Professional BoatBuilder Magazine

The rudimentaries of rudders.

By Steve D'Antonio , Jul 12, 2018

Even stoutly constructed rudders are vulnerable to deterioration over time, especially when mild steel or high-carbon-stainless steel is buried in composite foil sections, which inevitably become saturated with seawater.

Like other systems and gear aboard cruising and commercial vessels, rudders have terms to identify their parts and functions. When measuring a rudder, the span and chord are the vertical height and fore-and-aft width, respectively, while the top of portion closest to the hull is referred to as the root , and the bottom is called the tip . Another term frequently used when discussing rudder design, particularly for sailing vessels, is aspect ratio —simply the square of the rudder’s span divided by the rudder’s area. As a rule of thumb, longer, narrower rudders are more efficient than short, wide rudders, and the aspect ratio describes precisely this relationship. Thus, rudders on high-performance sailing vessels are said to have a high-aspect ratio. Walking around a boatyard one day and measuring a few cruising sailboat rudders, I came up with aspect ratios of between 1.7 and 2.1, while one high-performance sailing vessel’s rudder came in at 3.5. The 20-knot semi-displacement lobster yacht’s rudder I measured yielded an even 2.0 aspect ratio, which is considered respectable for this application.

More identifiable rudder components include the stock ; web or armature ; rudderport or log ; stuffing box or compression tube ; bearing ; gudgeon ; and pintle . Not every rudder has all these components.

Rudderstocks

The rudderstock is essentially a shaft or tube that protrudes from the top and sometimes the bottom, depending upon type, of many rudder designs. Because this component provides the primary connection between the rudder’s blade (the flat section that imparts the steering force) and the vessel’s steering system, its design, construction, and material are consequential.

Most stocks are made of stainless steel, bronze, or aluminum, while some are carbon fiber, and they may be solid or hollow. Stainless steel is by far the most common, but it has a penchant for crevice corrosion when exposed to oxygen-depleted water. Insidiously, corrosion nearly always occurs in places where it cannot easily be seen—such as inside many composite (fiberglass and core material) rudder blades and beneath flax-type stuffing-box packing (the problem is exacerbated when the vessel is used infrequently).

This all-stainless rudderstock and webbing is well crafted and ready to be covered with its composite shell.

Of the stainless steel alloys, some resist this corrosion better than others. Stainless-steel rudderstocks should be manufactured with strong, highly corrosion-resistant proprietary shafting alloys such as A22. The next best choice is 316L stainless steel, which also resists crevice corrosion well. Critically important is the L suffix, meaning “low carbon,” a requirement if it is to be welded, as nearly every rudderstock must be, to the support within composite rudders, or to all-metallic plate-steel rudders. Failure to source low-carbon stainless steel for the stock or the web leads to weld decay, sometimes referred to as carbide precipitation, where the region around the weld loses its resistance to corrosion and rusts when exposed to water.

Aluminum rudderstocks are nearly always tubular. Common on aluminum vessels to reduce the likelihood of galvanic corrosion, aluminum stocks are also relatively common on fiber reinforced plastic (FRP) vessels, particularly large ones. Rudder blades, particularly on aluminum vessels, are often fabricated from aluminum. Of the various aluminum alloys, only a few possess the necessary corrosion-resistance and strength necessary for use as rudderstocks. Of these, the 6000 series, and 6082 in particular—an alloy of aluminum, manganese, and silicon—are popular for this application.

Because aluminum, like stainless steel, suffers from corrosion, it should not be used as stock or web material in composite rudders. Referred to as poultice corrosion, it occurs when aluminum is exposed to oxygen-depleted water. Because oxygen is what allows aluminum to form its tough, corrosion-resistant oxide coating, the metal should never be allowed to remain wet and starved of air as it would be inside a composite rudder blade after water makes its way in around the stock and pintle.

Rudderstock material can corrode in way of the oxygen-starved environment around the packing in a stuffing box.

Bronze, a once popular rudderstock material, is no longer common in today’s production vessels. Although strong and exceptionally corrosion resistant (immune to crevice corrosion), bronze is not easily welded to attach to a rudder’s internal structural webbing, and has thus been supplanted by stainless alloys. Bronze rudderstocks, particularly those that have seen many sea miles, are also known for wearing, or hourglassing, within stuffing boxes, where the flax rides against the stock. If a bronze stock rudder is chronically leaky, disassemble the stuffing box and check for excessive wear. The same is true for stainless and aluminum stocks: chronic leakage is often an indication of corrosion at the packing. Finally, because of their galvanic incompatibility, neither bronze nor copper alloys should be used aboard aluminum vessels for rudderstocks or any other rudder or stuffing box components.

Mild-steel webbing welded to a stainless-steel rudderstock is a recipe for eventual corrosion and failure.

The webbing, or internal metallic support system, in most composite rudders must be strong enough to carry the loads of service and be made of the appropriate material. At one time, many rudders were built using stainless-steel stocks and ordinary, rust-prone mild or carbon-steel webbing. Inadvisably, some still are. The union between a stainless stock and FRP rudder blade is tenuous at best (the two materials expand and contract at different rates) and stainless steel’s slippery surface makes adhesion to the laminate resin a short-lived affair. Once water enters the gap between these two materials, it will reach the webbing and associated welds. Thus, all the materials within this structure must be as corrosion- and water-resistant as possible, and the core material must be closed-cell—often foam—and nonhygroscopic.

This destroyed foam-core and stainless-steel rudder reveals the conventional construction of such appendages.

Additionally, where possible, the stock should consist of a single section of solid or tubular material; i.e., it should not be sleeved, reduced, or otherwise modified or welded unless done so in an exceptionally robust manner. The webbing must be welded to the stock, but the structure of the stock should not rely on a weld that would experience cyclical, torsional loading.

The webbing in the form of a plate or grid should be welded to the stock with ample horizontal gussets (small wedges welded where the stock and webbing interface), which will reinforce welds 90° to the primary web attachment.

Whether the rudder is spade (supported only at the top) or skeg hung (supported at the top and the bottom), the stock must pass through and be supported by the hull. This is usually accomplished by a component known as a rudder log, or port. In its simplest form it’s a tube or pipe through which the stock passes. Nearly all logs incorporate two other components—a bearing and a stuffing box. The bearing may be as simple as a bronze or nonmetallic bushing or tube inside of which the stock turns; or it may be as complex as a self-aligning roller-bearing carrier that absorbs rudder deflection and prevents binding.

This rudder log is leaking, corroded, and poorly supported, with washers compressing into the backing plate and gelcoat cracking off.

The log transfers tremendous loads and must be exceptionally strong and well bonded to the hull. Fiberglass vessels should rely on a well-tabbed-in purpose-made tube (its filaments are wound and crisscrossed and thus quite strong) that is supported with a series of vertical gussets that distribute the load to the hull’s surrounding structure. On some spade rudder installations, particularly where the log is not, or could not, be long enough, an additional bearing is used at the top of the stock, above the quadrant, where it is supported by the vessel’s deck.

On metal boats the design is similar but with a metal tube welded in place, supported by substantial gussets. For vessels with skeg-hung rudders, the strength of the rudder log is still important. However, because the loads are not imparted by a cantilevered structure, logs used in these applications may be less substantially supported.

Stuffing Box

Unless the rudder log’s upper terminus is well above the waterline or on the weather deck, it is typically equipped with a stuffing box similar to those used for propeller shafts. But unlike a shaft stuffing box, the rudder’s stuffing box shouldn’t leak much, if any, seawater. Because the rudder turns slowly, friction and heat are not a problem. Packing (i.e., waxed-flax packing like that in traditional stuffing boxes) can typically be tight enough to stem all leakage, and lubricating it with heavy water-resistant grease will reduce friction and leakage.

Stuffing boxes that are above the waterline while the vessel is at rest, such as those on many sailboats, are often the most chronically leaky, because the packing tends to dry out and contract. To avoid this, liberally apply grease to the packing material itself; this requires partial disassembly of the stuffing box. Alternatively, a galvanically compatible (316 stainless or Monel for bronze stuffing boxes) grease fitting may be installed and periodically pumped with grease to keep the packing lubricated.

Rudder Bearings

Well-engineered rudder bearings support and lubricate the rudderstock.

Rudder bearings range from the basic rudderstock turning inside a bronze log, to the sophisticated aluminum, stainless, or nonmetallic roller bearings installed in a self-aligning carrier. For most cruising vessels, the choice of bearing is not as important as knowing which type of bearing is in use and its strengths, weaknesses, and maintenance needs. The simple shaft that turns inside a bronze log is durable and reliable but more friction-prone than roller bearings. If lubrication access or a grease fitting is available, it should be pumped with grease periodically, although most rudders rely solely on seawater for lubrication, which is perfectly acceptable.

This synthetic upper bearing worked fine in cool temperatures, but when it heated up in the sun, the material expanded and caused binding in system.

Nonmetallic sleeve and roller bearings, often made of ultra high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE), require no maintenance, are extremely slippery, and will not absorb water, an essential attribute for nonmetallic bearings. Delrin and nylon, for instance, will absorb water, expand, and lead to rudder binding. On several high-performance sailing vessels, I’ve had to replace nylon or similar bearings with UHMWPE to restore the steering to its proper specification and effort level.

Propeller Removal

Shaft removal should be possible with the rudder in place. This conventional skeg-hung rudder has a hole to facilitate shaft removal when the rudder is swung hard to port or starboard.

Whether a rudder is a spade or skeg-hung design, it’s important to determine how it will affect the removal of the propeller or the propeller shaft. Is there enough clearance between the shaft’s trailing end and the leading edge of the rudder to allow the propeller to be removed or to use a propeller removal tool? Can the shaft be slid out without removing the rudder? Some rudders are equipped with shaft-removal holes, while others are installed slightly offset from the centerline; or the rudder’s leading edge has an indentation to allow the shaft to be removed. The propeller should be removable without having to unship the rudder. The dimensional rule of thumb calls for clearance of at least the prop’s hub length between the aft end of the shaft and the leading edge of the rudder.

Rudder Stops