Escale de nuit

Chroniques d'un voyageur ordinaire.

- Mer & Océan

- Voyage interdit

Le tragique destin de Manureva (ex – Pen Duick IV)

Posted By Blog Voyage - Escale de nuit on 27/10/2020

Le Pen Puick IV est le voilier quatrième du nom. Racheté par Alain Colas, un ancien professeur un peu idéaliste qui rebaptisera ce voilier Manureva. Ce multicoque en acier est fiable et robuste

La naissance d’un multicoque performant

Lorsque Pen Duick IV est mis à l’eau, les records tombent. Ce multicoque en alliage est assez étrange est surnommée la pieuvre géante. Mais comment Eric Tabarly a pu imaginer un tel bateau?

Alors qu’il effectuait un convoyage sur un trimaran avec l’architecte Dereck Kelsall, il comprend l’avantage de ce type de voilier. Pour financer le voilier, Eric Tabarly vend les droits des interviews à venir à Paris Match et à RTL (radio Luxembourg).

Dès la mise à l’eau, Eric Tabarly est convaincu de la réussite de son voilier. En effet lors des essais Pen Duick 4 se montre jusqu’à deux fois plus rapide que Pen Duick 3.

Des débuts compliqués

La mise à l’eau du navire à lieu le 11 mai 1968. Il sort en mer la première fois le 15 mai. Mais le vrai problème c’est que l’Ostar, la course qu’Eric Tabarly a remporté en 1964 à bord de Pen Duick 2 part le 1er juin.

En quinze jours, il lui sera malheureusement très difficile de faire les réglages qui s’imposent sur ce type de multicoque qui est en plus un prototype. Contre toute attente Eric Tabarly réussira donc à prendre le départ. Mais dans la nuit du 1er au 2 juin, il heurte un cargo. Il revient donc à Plymouth pour faire réparer son voilier. Il repart après quatre jours de réparation. Puis lors de son nouveau départ c’est le pilote automatique qui tombera en panne, il revient à Plymouth pour le faire réparer. En repartant, le pilote automatique lâche de nouveau. Eric Tabarly décide donc d’abandonner.

Après cet abandon, Pen Duick IV retourne dans les chantiers La Perrière pour être réparée.

Eric Tabarly s’inscrit pour une nouvelle course, le Crystal Trophy. Malheureusement il connaît de nouvelles fortunes de mer. Le mât d’artimon démâte et le mât à l’avant subit un cintrage. De tous les Pen Duick ce voiler sera celui qui aura causé le plus de problèmes à Eric Tabarly.

Les records de Pen Duick IV

Les courses n’ayant pas réussi à ce multicoques révolutionnaire, son skipper décide de l’emmener aux Etat-Unis pour le vendre. Pour ce faire, il embarque avec lui son fidèle second, Olivier de Kersauson et Alain Colas. Lors de la traversée les trois compères sont obligés de s’arrêter sur l’archipel de Canaries. Une violente tempête balaye l’Atlantique Nord, les vents dépassent les 70 noeuds et il serait inconscient de se jeter dans la gueule du loup. Surtout lorsque l’on souhaite vendre le navire. Cette escale forcée ne l’empêchera pas d’établir un nouveau record pour la traversée de l’Atlantique soit 2 640 miles nautiques. Avec 10 jours et 11 heures, ce trimaran boucle le parcours avec une moyenne de 11 noeuds.

A la suite de la traversée Eric s’engage sur la course Los Angeles – Honolulu . Les multicoques n’étant effectivement pas acceptés sur la course. Cela n’empêche pas Eric Tabarly de « s’imposer » avec 20 heures d’avance sur le maxi-yacht Windward Passag. Et au passage il bat le record avec plus de 24 heures d’avance.

En 1969, Alain Colas décide de racheter à Eric Tabarly Pen Duick IV. A la suite de cette transaction et au vu de la fin tragique de l’histoire Eric Tabarly décidera ne ne plus jamais vendre de voilier à ses équipiers.

La disparition de Manureva

Alors que le skipper de cet (ex-Pen Duick IV) se lance dans la route du Rhum en 1978, il décide de passer en force sur la route du nord. La route la plus directe mais également la plus compliquée. En effet l’orthodromie est sur la route des dépressions qui déboulent de Terre Neuve ou d’Islande. Généralement ce sont les monocoques qui emprûntent cette route. Mais Alain Colas en a vu d’autres. D’ailleurs son baptême du feu se fera à bord de Pen Duick III, un solide ketch. A son bord il survivra à un terrible cyclone au large de la Polynésie. Mais voilà l’Atlantique Nord c’est une mer qui n’a pas forcément besoin d’un ouragan ou d’un cyclone pour être dangereuse. D’autre part un trimaran se comporte différemment qu’un monocoque, surtout dans le très mauvais temps.

Au large de l’archipel des Açores, le comité de course perdra définitivement la trace de Manureva (ex-Pen Duick 4) et de son skipper atypique Alain Colas.

La fiche technique du Pen Duick IV (Manureva)

Informations sur la coque du navire.

Longueur: 20,80 mètres

largeur : 10,70 mètres (maître bau)

tirant d’eau : entre 80 centimètres et 2,40 mètres

année de construction: 1968

matériau : alliage d’aluminium (de type AG4MC)

déplacement : 8 tonnes

architecte: André Allégre

chantier naval: Chantiers et Ateliers de la Perrière (Lorient)

Voilure de Manureva (ex-Pen Duick IV)

type de gréement : ketch Marconi (deux mats et voiles avec la chute arrondie)

surface au près : 107 mètres carrés

Êtes-vous d'accord avec notre politique de gestion des cookies?

- Classic Galleries

A LEGEND LOST AT SEA

- Author: SI Staff

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ORIGINAL LAYOUT

Alain Colas ismissing at sea. An intensive search has been conducted by planes and shipsacross a vast wedge of the North Atlantic. His last official radio contact waswith a French radio station on the afternoon of Nov. 16, from a locationthought to be north and west of the Azores. Colas was barely 35, yet he wasalready a man whose life contained the stuff of legend. He was one—some say No.1—of a breed so unique that most folks can only approximate in dreams what hedid in real life. He was a single-handed ocean sailor, one of the few who makeblue-water voyages alone, relying on the wind for power, their wits forcompany. And even among these extraordinary few, Colas stood apart, exuding anaura of isolation. There was a hint of the fever of obsession about him,although he tended to keep it under precise control.

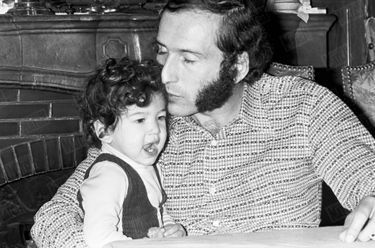

No man ever lookedmore like a sailor than Colas. He had black, curly hair and he affected thethick muttonchop sideburns of a 19th-century mariner. His face was seamed withsun-squint lines and he walked with a limp, the result of a sailing accident.The limp gave him an Ahab-like mystique.

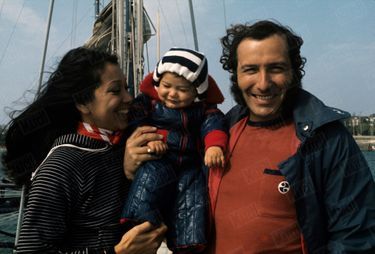

Colas spoke withdisdain about life in modern cities; indeed, years ago he had fled Paris forthe South Seas. He was married to a beautiful Tahitian who gave him a daughterfour years ago and twin sons last summer.

Colas, who hadturned 35 on Sept. 16, had traveled 130,000 miles under sail, five times aroundthe planet, when he was lost at sea. For some 50,000 of those miles—close totwo years, in total time—he was alone, including two transatlantic races fromPlymouth, England to Newport, R.I. Colas won the 1972 race, sailing the3,000-plus miles in a record 20 days, 13 hours and 15 minutes, which slicednearly six full days off the previous best time. Colas' Pen Duick IV was firstamong the 55 boats entered that year, and in 1976, the next running of theevent, he was third out of 125 starters. On this occasion he was at the helm ofthe controversial Club Mèditerranèe, the 236-foot four-masted schooner which hedesigned. It was, and is, the largest sailing ship to be built since beforeWorld War I, and he sailed it alone across the Atlantic in one of the worstseasons of storms in memory. In another of his celebrated single-handedvoyages, Colas circumnavigated the globe in 168 days, 57 days better than therecord set by Sir Francis Chichester in Gipsy Moth III.

In early NovemberColas was off once more; when last seen he was alone again at the helm of thetrusty old trimaran Manureva he had twice sailed around the world. This time hewas heading across the treacherous Atlantic on a race of 4,000-odd miles,starting at Saint-Malo on the north coast of France; his destination wasPointe-à-Pitre on Guadeloupe in the French West Indies.

Although Colas wasalone on his boat, he wasn't exactly alone on that reach of ocean. No fewerthan 37 other solitary sailors had left Brittany with him on the morning ofNov. 5 in a new transatlantic race for single-handers called La Route du Rhum.The name comes from the course: roughly the reverse of the route sailed byclippers and schooners whose holds were loaded with barrels of rum. It issomething of an upstart event in that the British have pretty much held thefranchise for such races with the London Observer's 18-year-oldPlymouth-Newport event. The French also trod on yachting tradition by offeringmoney as a reward—$45,000 for first prize and lesser sums for other places. Thewinner of the Plymouth-Newport race receives a 12-inch silver plate.

The Rum Race isabout half again as long as Plymouth-Newport, and while the starting field forthe inaugural event was mainly French, it also attracted such world-classsailing loners as Chay Blyth of Great Britain, Michael Birch of Canada andPhilip Weld of the U.S. The most optimistic entrants predicted that the winnerwould complete the race in three weeks. But Colas was more meditative about thecourse. He thought that the mean and unpredictable weather in the Atlantic inNovember, plus the tough windward tack into the prevailing westerlies duringthe first third of the race, would mean no one could reach Guadeloupe in lessthan 25 days—or not until Nov. 30.

Sailing the oceanalone is a romantic notion. It sounds like simplicity itself, a mere matter ofa brave man with a strong hand on the tiller and a sharp eye on the starsputting canvas to wind. Single-handed ocean sailing has the ring of an ultimatereduction of life's complexities, an escape to personal purity, a consummatehuman adventure.

Unfortunately,this isn't quite the case. Adventure and romance are there, certainly, but thesingle-handed sailor is far from being a free child of nature. One may view himas a man who should express himself in poetry, but to whom, in fact, the jargonof modern technology is more suitable. The single-handed ocean racer is almostas much a product of the space age as an astronaut is.

A month before therace, Colas was in Brittany, supervising the overhaul of the Manureva. The nameis Tahitian; it translates into L'Oiseau du Voyage in French, The Bird ofTravel in English. Parts of the boat were scattered about a cluttered machineshop near Saint-Malo. Colas watched intently through a welding mask as amechanic blazed away at a section of the rudder. Colas said something inFrench, removed the mask and switched to English. "This has come to be likeauto racing," he said, "so technical and so much demand for precisionto the last detail. We are very close to airplane techniques in design, shapingthe surfaces to put up the least resistance. Turn an airplane upside-down andyou have a boat, you see?" He looked around at the disarray of the machineshop, then sighed. "The race itself is almost a minor point. It is thepreparation that rates first, the attention to each technicality."

He spoke quicklyin French to the proprietor of the shop, then limped out into a radiant Octobermorning. He climbed into his car. "Let's go have a look at the oldgirl," he said. "She and I have been separated for most of a yearnow."

He careened overstony hills on narrow roads and pulled into a boatyard at the village ofTrinitè-sur-Mer. There, perched on pilings above the receding tide, satManureva.

The trimaranlooked nothing at all like a bird of travel. Indeed, she resembled nothingquite so much as a great steel water spider, a bizarre contraption paintedgrayish-blue. Still, she was oddly graceful, an interlocking arrangement of twolarge pontoons attached to a center hull by struts and beams. She looked to bemore cousin to a lunar lander than to the Pequod. The two needle-like mastswere of a light new alloy. Everything else was made of a stainless-steel alloythat was the best stuff available when the boat was built 10 years ago.Manureva was 35 feet wide and almost 70 feet long.

"She's aracing machine," Colas said admiringly. Then he shrugged. "But she is10 years old now and there are many boats in the race that are bigger and madeof all the newest stuff. There'll be bigger boats and younger chaps than I.Perhaps this old girl is already outmoded and gone past her day. But with theright skirt and a little makeup, she will look as fine as the new girls whowill be running with her."

Colas went aboard,followed by a worker who furiously took notes as Colas dictated what was stillto be done.

Manureva was aracing machine, all right, stripped of excess weight and creature comfort. Themetal struts were punched with holes to lighten weight. For the skipper, therewas a cramped little cockpit filled with stacks of charts and navigationalinstruments. A plastic dome offered minimal protection from storms. Inside thebare metal of the hull was a narrow cabin containing a galley with a gasheating plate and a bunk mattress fitted into a box to keep the sleeper frombeing tossed out of bed in heavy seas. One had to bend almost double to moveabout.

Colas looked intothis dark hole with affection. "This was my home for many months, reallyfor years," he said. "I'm as comfortable in there as if it was a snuglittle house with a hearth and a parlor."

Although the seaand a boat reflected all the warmth of home to Colas, it wasn't too long agothat they were alien to him; few sailors were born with less seawater in theirveins. He grew up in the hills of Burgundy, the son of a man whose livelihoodwas literally made of earth—his father was a potter and a ceramics manufacturerin the village of Clamecy. "He takes a handful of clay and turns it intowhatever you might think of," Colas said.

As a boy, the onlywater sport Colas attempted was kayaking on the local river. He attended theUniversity of Dijon, then the Sorbonne. It was there that restlessnessstruck.

"I began tocrave a more thorough life. I wanted more colors, more sun, more open ways,Colas said. In 1966, he left what he called "the polluted skies ofParis" and flew to Australia to become a lecturer in French at theUniversity of Sydney. It was there, at 22, that he discovered the sea. "Myfriends were sailors and racing enthusiasts and they took me out in a keel boatone afternoon. It was love at first sight. I went to the library and got everybook on sailing that I could carry. I learned a mainsail from a helm and,gradually, I became a good crewman."

In December of1967, Eric Tabarly came to Australia for the Sydney-Hobart race. Tabarly was acelebrated French sailor, winner of the 1964 Plymouth-Newport race and,although Colas was crewing on another boat, the two men became friends. Whenthe race was over, Colas joined Tabarly's crew and sailed for NewCaledonia.

This first cruisewas almost Colas' last: they were caught at sea by Hurricane Brenda's 100-mphwinds and 35-foot waves. With sails shredded and rigging snarled, the boatbarely made the harbor afloat. But it was adventure enough to hook Colas onsailing and by 1968 he was back in France on the Breton coast where Tabarly wasbuilding a trimaran for that year's Plymouth-Newport race.

Tabarly had becomeentranced with the idea of a multihulled racer, with none but the barestessentials. He figured it could cross the Atlantic in the faintest of winds,yet hold its own to windward in heavy stuff. The result was a prototype thatcritics said looked like a floating tennis court. In the spring of 1968 therewas a rash of strikes throughout France and the boat was barely finished intime for the race. Tabarly named her Pen Duick TV, after a black sea swallow ofBrittany, and set sail. Barely out of Plymouth Harbor, he collided with afreighter and limped back in for repairs. He took off again and the automaticsteering broke down. Tabarly gave it up and went back to France.

Although out ofthe race, Tabarly nonetheless figured the time was right to cross the Atlantic.Then he would go through the Panama Canal and cruise the Pacific. Colas signedon as crew. They had a good year, putting in at such romantic spots as Tahiti,Hawaii and Samoa, setting a batch of records along the way.

Tabarly was notentirely comfortable with a multihull, however, and he decided to sell PenDuick IV. While in Los Angeles, he scrawled a crude FOR SALE sign and stuck itto the mast. There were no bidders. But Colas had come to love thefreakish-looking craft and wanted it. To raise the money, he began cruising thePacific in an old schooner, the Naragansett, working as a free-lance journalistand photographer. By 1970 he had made enough money for a down payment, andTabarly agreed to sell Pen Duick IV for $50,000. Now she belonged to Colas—oncredit. He used her as his journalist's workboat. "I roamed the Pacific forstories," he said. "And always I was gaining knowledge of the boat,sailing with fewer people, until I knew that one day I would go it allalone."

In the fall of1971, Colas was in Tahiti, gripped with a new obsession: he would sail in the1972 Transatlantic race. A solo journey home to France, a mere 14,000-milejaunt, would be just the thing to get him in shape. It was about that time thatColas met a Tahitian named Teura Krause.

"She was verydark and very Tahitian and we were close from our first meeting," Colassaid. "She became my wife, but that is not a good enough word. We are lifecompanions. I had to hurry to make the starting line at Plymouth, but we didn'tfeel like parting. So we sailed together.

"But shesuffered seasickness beyond belief. Also, a pack of 30 or 40 sharks followed usfor days, dashing in to snap and attack anytime we made any move near thewater. Finally, after a 24-day passage out of Darwin into Maurice-La-Reunion,in the Indian Ocean. Teura flew on ahead and I was left to make my first majorsingle-handed passage."

Teura left him inmid-December and Colas made his last landfall at Mauritius on Dec. 16, 1971. Hesailed non-stop past Madagascar, around the Cape of Good Hope, and up the coastof Africa to the north coast of France without ever putting a foot on land. Heaveraged 125 miles a day and made the trip in 66 days.

At the boatyard inBrittany last fall, as he gazed pensively at the familiar lines of the formerPen Duick IV, Colas said, "We have sailed some lovely miles alone, the oldgirl and I, but I don't go out on the ocean for the sake of being on my own.Solitude isn't what I seek. I must have a sense of purpose behind a solitarysail and that overcomes the solitude. There are loners of the sea, men who wishnot to speak to others and who avoid all ports of call because that is the cutof their personality. I felt that old Joshua Slocum, our spiritual father asthe first man to do a single-handed circumnavigation, was the one who treasuredhis aloneness. I don't know that he actually disliked people, but I think theold captain was a bona fide loner. But for me, a single-handed sail is part ofan idea that leads to something other than solitude itself."

Whatever thepurpose behind a single-handed sail, solitude is as intrinsic to the game asthe sea itself. And as Colas went on to say about his colleagues, "We are aspecial brand of sport maniacs who derive our pleasure from our own lonelyactions instead of performing in a gymnasium or a pool or a stadium. Our sportinvolves long hardships and strange times, but it makes us very happy."

Whether its mainappeal is hardship or happiness, solitary ocean racing as an organized sport isnot yet 20 years old. It had its inception in 1960 when five boats leftPlymouth bound for New York, 3,000-odd miles away. The largest boat that yearwas Chichester's Gipsy Moth III, at 39 feet considered a possibly unmanageablehandful for a man at sea alone. Chichester won the race in 40 days and 13½hours. Over the years the number of single-handed sailors has increased, theboats have grown longer and lighter and computers are used in navigating andweather forecasting. But while the technology has changed greatly since thedays of the clipper ships, human beings have changed hardly at all. At seaalone, they are as susceptible today to strange visitations and hallucinationsas they were a century ago.

Slocum, thecelebrated 19th-century salt, was the first and perhaps still the greatest ofthe world's lone circumnavigators. Slocum spent more than three years on avoyage that began on April 24, 1895, when he headed out of Boston in his35-foot sloop, Spray. He sailed 46,000 miles in all, and during much of thetrip, Slocum, who was 51 when he started out, indulged in countless hours ofconversation with a cheerful, bearded fellow who periodically appeared on Sprayto help with navigation—a courteous man who introduced himself as the pilot ofColumbus' Pinta, which had sailed the seas some 400-odd years earlier.

Suchhallucinations are not uncommon. During the 1972 Plymouth-Newport race, amedical survey was taken to study the mental, emotional and physical effects ofthe race on several of the entrants. Through logbooks and interviews, theyreported impressions of their lonely journeys. One man recalled that throughoutthe trip he had heard "the usual high-pitched voices" in his riggingcalling "Bill! Bill!" Another said that after 56 continuous hours atthe helm, he noticed that his father-in-law had appeared at the top of themast, where he was quietly sitting. The sailor didn't find this surprising orunusual. Another competitor reported that he was lying on his bunk when heheard a man at the helm putting the boat onto another tack. When he went ondeck to investigate, the man passed him in the passageway coming down. Theydidn't speak and he didn't recognize the man, but when he checked the bearing,he found that the boat had, indeed, been put about and the course changed.Still another sailor reported that, on his 33rd day at sea alone, he wasraising his sails when he noticed a baby elephant in the sea and thought,"My, what a strange place to put a baby elephant." A few minutes laterhe saw that it wasn't a baby elephant at all but a Ford automobile. Later herealized that in fact it had been a whale.

The single mostserious problem is the shortage of sleep. Each sailor handles it in his ownway. Some never sleep more than an hour at a time. Others, like Colas, woulddoze off for three hours at a stretch, with automatic steering vanes set tohold course. But with sleep always uncertain, half-world sensations arise."My mind was completely separated from my body," one sailor reported."I just used my body to get around the boat."

Then come theterrors of storms, and almost as fearsome, calm. Some of the logbook entriesdealt with the suffocating frustration of a perfectly windless sea. One manwrote, "I feel like a prisoner in a well-stocked cell, but with no onearound to tell me the date of the termination of my sentence." Another keptlogging the word "becalmed," writing it larger and larger each dayuntil, finally, the single word BECALMED covered two full pages.

The changes inmood of men alone at sea are enormous, ranging from highs where they sing anddance hornpipes all alone, to blackest depressions. During the early hours ofthe 1968 race, one sailor inscribed in his log some noble lines from "TheSea" by Louis MacNeice:

Incorrigible,ruthless, It rattled the shingly beach of my childhood....

A day later thesame man scribbled darkly, "I must be nuts!"

In spite of this,most single-handed sailors say that the sense of isolation is neitherfrightening nor uncomfortable. One sailor said, "There is an intimate andcomplex relationship with the natural environment and the creatures thatinhabit the sea and the air, so that the lone sailor never feels abandoned orrejected." Colas said last year, "There is no sense of being aninfinitesimal, helpless speck in the universe when you are sailing in solitude.This is because you become the center of your own universe, you give birth toyour own island, to your own nation when you sail alone. Soon enough, you sailher right out of the ocean and into your own small circle of being. Perhapsthat is too existential, but that is the way it comes to seem."

What about fear?"Not a factor," Colas said. "Fear is a result of the unknown. Anawareness of danger is not fear. I have many times felt my heart jump into mymouth at the sight of a mighty mountain of the sea hovering over me and mylittle boat. But I know we will climb up that steep wall and reach the top andslide down unharmed. We know things, so we need not fear. We know this earth isnot a disk and that we may not sail to the edge and fall off. We know a stormis not Neptune shaking his trident and aiming his wrath directly at a poorsailor at sea. We know storms are caused by cold air moving in over hot air.What we know, we do not fear—and we know much these days."

Is religion anessential companion to the single-handed sailor? "Ah, well, that maydepend," said Colas. "I am deeply Christian; I was raised as aCatholic. But perhaps I have read too much of Ralph Waldo Emerson and thetranscendentalists, and perhaps they are too much to my liking. I believe man'sfate is in his own hands. It is good to have religion, but I know that God willnot be coming down to help me rig a genoa, and thus I get a good hold of thesail by myself. There are times when I might be thankful to see God there withme in the cockpit on a black and tumultuous night, but I know that I cannotcount on that. He is not too reliable that way, I think, and therefore I mustbe perfectly reliable alone."

To Colas, the trueexhilaration in the life of a single-handed sailor lay in its stark contrastwith the ordinary perceptions that most men come to take for granted. "Thiskind of sailing is a way of knowing yourself a little better and of enjoyinglife more intensely," he said. "The risk sharpens you, and beingdeprived of so many things makes you sensitive to the true wonders of life whenyou return. You rediscover how wonderful it is to be close to people again. Thedeprivation of social warmth for so many weeks sharpens the sensations offriendship and of love, and you have never known before how immensely importantpeople are to you, how warm they are and how necessary."

After the voyageto Brittany, Colas had mastered himself and the eccentricities of Pen Duick IVat sea and was well prepared for the shorter trip between Plymouth and Newport.His boat was well known, partly because of Eric Tabarly's former ownership andpartly because of the records it had set in the Pacific. But Colas wasrelatively unknown and he was definitely not the favorite.

The boat to beatwas a radically new 128-footer called Vendredi 13 (Friday the 13th), bankrolledfor $250,000 by French film director Claude Lelouch. It would be skippered byJean-Yves Terlain, a veteran single-hander. Vendredi 13 was a three-masterdesigned to churn steadily through heavy windward seas; Colas' boat, bycontrast, was meant to pick up faint breezes and skim the surface.

As the weatherworked out, Pen Duick IV was the perfect boat. Vendredi 13 stuck to the sea asif it were glued when winds were light—and a good part of the voyage was madein whispering breezes. Colas finished 12 hours ahead of Terlain. When reportersasked the victor if he had experienced any trouble, Colas shrugged and smiled."After 66 days, what is another 20?" he said.

Spartan quartersaside, Colas had lived in style at sea. He was well stocked with Camembert,Pont l'Ev‚Äö√†√∂‚Äö√ë¢que and Livarot cheese, patè from his home village and tripe à lamode de Caen. "I bring a special Burgundian approach to provisions," hesaid. "I always cook three meals a day at sea, always. I keep some hardtackstuff to put in the pockets of my oilskins for long hours at the helm, and Ihave some tinned foods on hand, but I like to travel with fresh things. Cabbagekeeps for months, and I bring eggs and onions, which are known as sailor'scaviar. I always bring garlic, because how can you cook without garlic? And Ibring a few bottles of wine, because how can you cook without wine? Sitting atmy little stove, browning nicely my onions and stirring up the fragrances ofhome with a wooden spoon—these things warm you up in many ways. And even thoughit may sound indulgent, it is not. I consider myself as a machine, a bit ofmechanical equipment, and just as an engine works better on excellent petrol,so does a man."

One form of petrolColas never used was liquor. "It is too dangerous at sea," he said."I am always flabbergasted at the amount of weight our English friendssometimes take along in ale and grog. Whoever must enhance his perception oflife with this extra stimulant, he has a poor grasp of things." (Colas'attitude toward alcohol is in the minority among single-handed sailors: SirFrancis Chichester rarely left port without a great store of whisky and beer,and a few years ago an Australian dentist may have set quite another kind oftransatlantic record by guzzling 23 dozen cans of beer in a 30-day voyage.)

After the 1972Plymouth-Newport victory, Teura told the press, "Up to now, we haven't hadthe money to get married—everything has gone into the boat. So we had to winfor our marriage, for our future, for everything." And the victory didbring Colas more than a silver plate. He got book contracts and endorsements inFrance, where single-handed racing is a surprisingly popular sport. One of hisbooks sold 200,000 copies, the money giving him further freedom to sail as hewished.

What Colas didnext was to circumnavigate the world alone in his trimaran (then renamedManureva). He departed Saint-Malo in Brittany in September of 1973, sailedaround Africa to Sydney, continued across the Pacific, around Cape Horn andback to Saint-Malo. He believed that any man who could negotiate thetreacherous straits at Cape Horn would achieve a special and praiseworthygoal.

"Cape Horn isto sailing as the Eiffel Tower is to Paris," he once wrote, "[it is]the most beautiful page in the history of the sea."

The first leg ofthe trip, 14,640 nautical miles to Sydney, took him just 79 days, beating allsingle-handed records. He arrived in Australia on November 27, 1972, laid overfor a month, then set out across the Pacific five days after Christmas. Hisboat carried a collection of books, letters and logbooks by captains andcrewmen who had circumnavigated a century before. "I was rubbing minds withthe ancient mariners," said Colas. "Their ideas and their words, themythology they created, were my companions and I was greatly affected by themand their ideas."

One idea that cameto be a compulsion during the second half of the voyage was an increasinglydesperate desire for speed. "I was driving the boat as hard as she could bedriven day after day," Colas said, "and soon the complexion of the tripchanged. I was obsessed, spurred to sail faster. An idea was growing inside ofme, and on the 160th day at sea, it peaked like a child in a mother's belly. Iwas pregnant with the idea for a new and faster boat."

Theround-the-world trip was a success: 30,067 miles in a record 168 days.

Back in France inthe spring of 1974, Colas began to design a massive ship that he would sailalone in the 1976 Plymouth-Newport race. He was still thinking speed."Those ancient mariners knew the secret," he said, "but I knewsomething was missing on my modern boat. What? It was length. When I roundedCape Horn, I topped 18 knots in the best conditions, but I wanted a boat thatcould do more. I wanted to design a boat that could do 29 knots and sustain asteady 20 to 21 knots day after day."

Colas beganorganizing the project. He made dozens of sales talks to potential sponsors,contacted steel and sail companies, tested model hulls in wind tunnels andwater tanks. About $1 million was needed. He gave lectures to raise money (from$1,000 to $1,800 per appearance), wrote more books and sold films made duringhis voyages. He convinced a steel company to give him 150 tons of raw iron orein return for a TV documentary covering the building of the ship. He inducedFrench naval architect Michel Bigoin to work with him on the hull design. Andultimately the great ship began to take shape.

She would be afour-master, with masts 105 feet tall. Each of her four mainsails measured1,035 square feet, each of her four foresails 2,205 square feet, and there wasa 1,071-square-foot spinnaker—a combined sail area of 14,031 square feet. Thehull was 236 feet long, longer than a Boeing 747, with a 36-foot beam, a draftof 18 feet and a displacement of 280 tons. Much of her rigging would be so faraway from Colas at the helm that he would need TV cameras and computers tomonitor the condition of the sails.

Finally, Colas gota major sponsor. The Club Mèditerranèe, the global resort firm based in Paris,decided to give $600,000, the cost of the rough hull. Colas would name hisgrand bateau Club Mèditerranèe.

"They gavemore than money," he said. "They gave trust and countless hours ofcommitment by their best men. They no longer own the boat; she is all mine andI could name her Alain Colas II if I wished. But she'll remain ClubMèditerranèe. They did not waver in their faith in me—even after I did thatbloody stupid thing on a joy ride."

The accidenthappened on May 19, 1975, in the tranquil harbor of La Trinitè sur Mer. Colasand Teura, some friends and a couple of crew members were returning from aday's sailing aboard Manureva. "It was only an afternoon joy ride, and myconcentration was not complete," Colas said. "I did not have my sheathknife at my belt, as I always do at sea, and I only had a small folding knifein my pocket. We were charging through the boats and moorings in the harborbecause the mainsail had gotten wedged at the top of the mast and I felt weshould slow down. I jumped forward to put down the anchor. The big hook fellover, 100 pounds or more, and I turned on my left foot to return to the helm.Ordinarily I would be watching the anchor line snake out, but this time I didnot. My right foot was above the uncoiling line. A loop sprang up and lassoedmy foot above the ankle.

"It sawedswiftly through the skin, sliced the muscle, bit through the bone, and by thetime I managed to get my knife out of my pocket and the blade opened I could nolonger see my foot. Only the naked end of the tibia bone where it had been cutthrough. The knife cut the running line very briskly, but by then all that wasattached to my foot was the Achilles tendon. I fished the foot up by the tendonand I knew enough to press the artery in my knee to slow down the rush ofblood.

"The majorreaction I had at the moment was one of annoyance. The boat was still movingquickly and I had to give orders. I was annoyed that I could not use my handsto give signals because I had to continue pressing the artery. And there wasthe severed foot itself to hold against my leg. I had to keep my balance on myone good foot and keep giving orders to bring the boat to a standstill.

"A friend wasthere who had had medical experience during the war in Algeria. He put on atourniquet and kept me from spilling too much more blood. My wife played thepart of a siren with her screams and woke up the village. An ambulance came andsped me to a tiny hospital 40 miles away. The surgeon there didn't know whatelse to do but some ax work further up the leg to get it organized for a laterfitting of wood perhaps. I wanted none of that.

"Eventually wewere able to raise Professor Jean-Vincent Bainvel in Nantes, a specialist inorthopedics, along with a colleague in cardiology well acquainted with thelace-work of veins and arteries. We raced to Nantes, which is about 85 milesaway, and by the time they put me in the operating room, it had been eighthours since the foot was pulled off. I was extremely fit and they decided togive it a go—to reattach the foot where it belonged."

The operationlasted seven hours and involved an intricate stitching of lengths of vein andarteries from other parts of Colas' body into the leg and severed foot. Overthe next seven months, there were 22 more operations involving skin grafts, andfurther work on the circulatory system. Miraculously, Colas kept his foot. Itwas almost as numb and stiff as if it were indeed made of wood, but it wasalive and well in its own way.

"I have neverwanted to be a surgical hero," said Colas. "I'd rather be a sailinghero. But I prefer my own foot to an artificial construction. One gets to likeone's own things, you know. And it has also added a rather impressive newweather-forecasting aid to my sailing. The foot is very sensitive to any changein the humidity—I find it as reliable as a barometer in most cases. Sometimesmore reliable."

The trauma of theaccident was short-lived: Colas' obsession with the building of his new boattook over almost immediately. On the second day after his foot was "splicedback," as he put it, Colas signed a contract to begin construction of thehull. For the next several months, he masterminded all of the initialconstruction from his hospital bed. "The project literally pulled me out ofbed," he said. "One year and one week after the accident, I was makingfinal preparations to start the race in my dream boat."

Club Mèditerranèehad indeed been built and fitted out in the year, and it was an incredibleracing machine. But the British race sponsors found it rather an irritation.Bitter arguments arose over the entry of such a behemoth. The British insistedthat Colas sail his beast on a 1,500-mile qualifying run instead of the 500miles required of the other entrants. Colas had no trouble: he finished the1,500 miles in just over six days.

The sponsorssearched for other ways to disqualify him, according to Colas, but their rulesput no limits on size, and nothing could be done. (Since then, race rules havebeen changed and no boat longer than 56 feet is allowed.) The Route du Rhum hasno limitation on maximum size, a policy Colas endorsed. "I believe thereshould never be a limit to the audacity of this sport," he said.

For the 1976Newport race, Colas wore a special boot to keep more of his weight supported bythe knee instead of by the still-weak foot. Although his makeshift circulatorysystem was beginning to function, it was far from perfect.

"One arteryand one vein were back at work," Colas said, "but the vein was notdoing its cleansing job very well. I could hardly totter more than seven hoursout of every 24 in a standing position. The other 17 hours I had to keep thefoot in a higher position than the leg to allow it to drain and circulate theblood properly. On board ship during the race, I had to pace my effortscarefully. When I had been standing too long and still had work to do about theboat, I simply had to crawl."

The 1976 race wasthe roughest ever run. The weather in the Atlantic was savage, with winds andstorms battering the entire field. Of the 125 starters, 37 boats retired andfive sank; two men were lost. Some sailors reported winds up to 80 knots. Sailswere popped off, masts snapped, automatic steering gear fouled. Through thesedays of tempest, Colas hobbled about his huge vessel, setting sails manually asthe regulations required, fighting to make headway and at the same time keephis sails from being blown out. But he, too, fell victim to the terribleweather and was forced to put in at Newfoundland to repair his sails.

It all proved tobe part of a bitter experience for Colas. "There was—and is—nothing thatcan go faster across the ocean under sail than my four-masted old girl.Nothing," he said. "But it was a very hard year on the Atlantic. Myadversities were many. Some newsmen were reporting that I was running second tomy old friend Eric Tabarly. Unfortunately, I believed that. Actually, it turnedout that I was two days ahead of him; had I known that, I wouldn't have stayedso long in Newfoundland."

But Tabarly hadfinished first in his 73-foot ketch Pen Duick VI. He was exhausted after 23days, 20 hours and 12 minutes on the raging Atlantic, most of it with hisself-steering rudder out of whack. Club Mèditerranèe glided into Newport out ofa heavy mist in an elapsed time of 24 days, 3 hours and 36 minutes, whichincluded Colas' layover time. He was second man in, but he was assessed a58-hour penalty, dropping him to third. It was claimed that he had illegallytaken passengers aboard when he left the boatyard in Newfoundland to return tothe racecourse.

The loss of therace was a blow to Colas, but he maintained a proud posture in discussing theoutcome. "I have nothing to prove," he said. "I have my owncontentment."

Colas returned toTahiti in 1976, where he carried paying passengers on joy rides aboard ClubMèditerranèe. But he hadn't retired from racing and when the Route du Rhum wasannounced early in 1978, Colas was one of the first entrants.

"I love torace and I ache when I am too long away from a race," he said. "Butdon't forget, I must work for my boats. Sailing has been a sport too much forthe sons of rich men. There has never been enough professionalism in it. Andprofessionalism is the truest democracy. If there were more money inracing—sponsors and money prizes as in the Rum Race—then a poor young man couldparticipate in his sport just as the rich do."

As for his hopes,he said shortly before leaving, "My boat and I, we sail at a good pace. Andwe are good in all weather. I think it will take 25 days to finish, but otherssay three weeks or only 18 days. Well, good on them if they can do it. When Iarrive, if I find some others have made harbor sooner than I, I shall say,'Bravo to you!' And then I shall continue on and sail my old girl home toTahiti. It will be the boat's third trip around the world. She has earned arest and I must spend more time with my family.

"If I am firstacross the line I will say, 'Bravo, old Manureva, bravo!—and I shall still setsail with her for home. I will feel that I am a winner either way."

At about 4 p.m.last Nov. 16, the Saint-Lys radio station on the French coast near Bordeauxreceived a message from Alain Colas. It was quite cheerful and optimistic. Hewas west of the Azores, proceeding nicely, he said. The operator warned himthat his signal was weak and full of interference, suggesting that his batterywas failing. That was his last known message.

The night of the16th, a storm hit the area where Colas had been. Winds rose to more than 50 mphwith waves cresting at 25 feet or so. The conditions were bad, but notcritically so for a man of Colas' experience. That night, ham radio operatorsin Lisbon, Portugal, and Ostender, Norway heard a Mayday distress signal and acall for "immediate assistance" from an unknown vessel at sea.

The winner of theRoute du Rhum, the Canadian Michael Birch, arrived in Guadeloupe on Nov. 29.After 4,000 miles of ocean racing his margin of victory was just 300 yards overMichel Malinovsky of France. Philip Weld of Gloucester, Mass. was third. One byone, the other boats appeared at Pointe-à-Pitre. The last two arrived on Dec.9. Only Colas was missing.

On Dec. 1, theFrench Navy dispatched four planes—two to the Azores, two to Guadeloupe—tostart a concentrated, 12-hour-a-day search for Manureva and Colas. Theycrisscrossed some two million kilometers of ocean, flying alternately at 6,000feet and 1,500 feet. There was no sign of boat or debris.

The search planeswere recalled and the French Naval Ministry canceled the search Dec. 28 aftercovering a five-million-square-kilometer area in 450 hours of flying time.Little hope remains. It now seems likely that the sea has claimed AlainColas.

Colas and trimaran Manureva before fateful transatlantic trip.

Size equates with speed, Colas figured: the 236-Foot Club Mèditerranèe was the result.

After sailing to Tahiti in 1971, Colas met and married Teura. More than a wife, "she is my life's companion," he said.

Looking for Colas and Manureva, planes searched the sea between the Azores and Guadeloupe, Alain's destination.

NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN

Visit Schedule Prices Combined offers

You are here

Éric Tabarly – His Yachts

Three of the Pen Duick yachts were built in the Perrière shipyards in Lorient : Pen Duick III the schooner, Pen Duick IV the trimaran and the first large multihull (which would become Manureva) and Pen Duick V, a 10.70m monohull, the precursor of today’s 60’ monohulls (such as the Vendée Globe yachts).

5 Pen Duick yachts

are still sailing

On view at the pontoon at

the Cité de la Voile

during a stopover

Pen Duick Éric Tabarly's first sailing boat

A 15m auric cutter designed in 1898 by the Scottish architect W.Fife III, Jr. and built in Ireland under the name of Yum. Guy Tabarly, Eric’s father, purchased her in 1938 and the family sailed on board until 1947, when she required extensive work. Éric Tabarly purchases her from his father in 1952, virtually a wreck. He would save her by laminating a mould of her hull with a polyester resin, a first at the time for a hull of its size. From 1959 to 1962, he completed numerous sailing tours and regattas aboard Pen Duick. She was restored once again between 1983 and 1989 by the R Labbé shipyard. It was aboard this boat that Éric Tabarly disappeared at sea during the night of the 12th of June 1998 off the coast of Wales.

Architect : William Fife III junior, Scottish architect Shipyard : Gridiron and Workers in Carigaloe near Crosshaven, Ireland

Pen Duick II The Transat Bakerley 1964

This is the first yacht that Eric Tabarly designed specifically for a race: the 2 nd edition of the English solo Trans-Atlantic in 1964.

A plan by G. Costantini conceived in his shipyard in Saint-Philibert. Éric Tabarly won the race in 27 days ahead of F. Chichester, the winner of the previous edition. Pen Duick II then received two new riggings to improve performances when sailing with a crew and light winds and to be more competitive in the CCA in America. The yacht was sold to the National Sailing School in Quiberon in 1967. Pen Duick II helped Éric Tabarly accumulate considerable experience in just two years and served as a design basis for the Pen Duick III. She was partly built in 1994 at the Pichavant shipyard. She now sails from the ENV (National School of Sailing).

Architect : Gilles Costantini and Éric Tabarly Shipyard : Costantini in Saint-Philibert

Pen Duick III the largest aluminium hull

Éric Tabarly’s Pen Duick III has received the most racing awards. An extrapolation of Pen Duick II, designed for the solo Trans-Atlantic race in 1968, but also for crewed races.

The year of its launch in 1967, Tabarly became the RORC champion by winning all the races in which he participated. A progression of Pen Duick II, constructed in aluminium and whose hull and keel were tested in a towing tank. It was a first for its time as were the sponsorships deals required to achieve the construction budget. Since then, she continues to ride the seas of the world, crewed or solo; the Vendée Globe Trans-Atlantic, the Whitbread, the Route du Rhum and the

Trans-Atlantic Lorient-Saint-Barthélemy-Lorient. In 2000, Pen Duick III joined the Pen Duick Cruising Club under the management of Arnaud Dhallenne.

Architect : Éric Tabarly and the Perrière shipyard Shipyard : Chantiers et Ateliers de la Perrière in Lorient

Pen Duick IV the first racing trimaran

A revolutionary trimaran in 1968 but unfortunately was not launched in time to conduct her final adjustments before the Transat due to the events of May 1968.

André Allègre and the Perrière shipyards designed an extremely light 20m yacht destined for the high seas. Built in aluminium, it incorporated many innovative features: pivoting masts with a ketch rig and fully battened mainsails, connecting arms in aluminium tubes joining symmetric floats to the central hull. A collision and autopilot problems meant that the Pen Duick IV failed to finish the Transat in 1968 but went on to win it in 1972 with Alain Colas. Manureva (its new name) disappeared during the 1 st Route du Rhum with Alain Colas the 16th of November 1978.

Architect: André Allègre and the Perrière shipyard Shipyard : Chantiers et Ateliers de la Perrière in Lorient

Pen Duick V thes first ocean racing yacht to feature ballast thanks

A 35’ prototype specially designed for the solo race in 1969: The Trans-Pacific San Francisco to Tokyo organised by the Slocum Society.

Pen Duick V was the precursor for current 60’ monohulls with her ballasts, deep and fine keel, her minimised rake and broad rear lines. The gliding hull featured the same redan style as motorboats. Éric Tabarly brilliantly won the race in 39 days and 15 hours, 11 days ahead of his nearest rival. The yacht was financed by the Port of St. Raphael who put her up for sale after the race.

Architect : Michel Bigoin, Daniel Duvergie and the Perrière shipyard Shipyard : Chantiers et Ateliers de la Perrière in Lorient

Pen Duick VI The solo Trans-Atlantic 1976

Éric Tabarly’s first Class 1, he had a soft spot for this yacht designed especially for the first round the world race, the Whitbread 1973-1974. Pen Duick VI had to be built in record time by the naval shipyard in Brest to make it to the starting line. All his chances of winning were, however, ruined by two dismastings during the 1 st and 3 rd legs. In 1974, the Bermuda - Plymouth was the first of many races that would be won by the ketch, in 1976, the Atlantic Triangle and the solo Trans-Atlantic in June. This race is undoubtedly the hardest Eric Tabarly ever participated in, confronting five consecutive storms aboard a yacht designed for a crew of 14, without autopilot (broke down four days after the start). The grand maxi would set off again in 1981 for the race around the world under the name of Euromarché. She finished 5 th out of 27 although surpassed by her competitors. In the 21 st century, Pen Duick VI continues to ride the world’s oceans as part of an educational sailing programme visiting Iceland, Greenland, the Caribbean, Patagonia, Antarctica.

Architect : André Mauric Shipyard : Naval Shipyard Brest

- Scores en direct

- Accueil Football

- Calendrier/Résultats

- Ligue des champions

- Premier League

- Toutes les compétitions

- Accueil Tennis

- Calendrier ATP

- Calendrier WTA

- Accueil Cyclisme

- Courses en direct

- Tour de France

- Tour d'Espagne

- Dare to Dream

- Accueil Sports d'hiver

- Tous les sports

- Accueil JO Paris 2024

- Olympic Channel

- Mon Paris Olympique

- Accueil Rugby

- Coupe du monde

- Champions Cup

- Accueil Auto-Moto

- Goodyear Ready For Anything

- Accueil Athlétisme

- Ligue de Diamant

- Ch. Monde outdoor

- Ch. Monde indoor

- Accueil Basketball

- Betclic Élite

- Toutes les Ligues

- Accueil Boxe

- Accueil Cyclisme sur piste

- UCI Track Champions League

- Accueil Cyclo-cross

- Accueil Equitation

- Accueil Formule 1

- Classements

- Accueil Golf

- World Ranking

- DP World Tour

- Accueil Handball

- Championnats du Monde

- Championnat d'Europe

- Accueil Judo

- Accueil MotoGP

- Classements Moto GP

- Accueil Natation

- Championnats du monde

- Accueil PTO Tour

- Paris, la vie sportive

- Accueil Snooker

- Northern Ireland Open

- Tous les championnats

- Accueil Speedway

- Accueil Sports universitaires

- Accueil Triathlon

- Accueil UCI TCL

- Classement messieurs

- Classement dames

- Accueil Volleyball

- Marmara SpikeLigue

- Ligue des Champions

- Ligue Mondiale

Un marin et un bateau de légende évanouis dans l'océan : 1978, le dernier voyage de Manureva

:focal(202x137:204x135)/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2019/11/27/2725182-56325666-310-310.jpg)

Mis à jour 20/04/2021 à 12:03 GMT+2

LES GRANDS RECITS - Le 5 novembre 1978, Alain Colas, le marin "star" des seventies, prenait le départ de la première édition de la Route du Rhum sur son mythique trimaran Manureva, l'ex-Pen Duick IV d'Eric Tabarly. Onze jours plus tard, après une ultime vacation radio, il s'évanouissait dans l'Atlantique, au large des Açores. On n'a jamais rien retrouvé, ni de lui, ni du bateau. Il avait 35 ans.

Les Grands Récits - Alain Colas

Crédit: Eurosport

- L'intégrale : Retrouvez tous les épisodes des Grands Récits

Newport 1964, Tabarly écrit le premier chapitre de sa légende

12/09/2023 à 12:22

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2021/04/16/3115448-63864688-2560-1440.jpg)

Samedi 4 novembre 1978 : Derniers préparatifs pour Alain Colas sur son Manureva, à la veille du départ de la Route du Rhum.

Crédit: Getty Images

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2021/04/16/3115622-63868168-2560-1440.jpg)

Alain Colas et son épouse, Teura.

Après la Route du Rhum, cap prévu sur Tahiti

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2021/04/16/3115508-63865888-2560-1440.jpg)

Manureva, plus qu'un bateau, un mythe englouti.

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2021/04/16/3115510-63865928-2560-1440.jpg)

Alain Colas à bord de "Club Méditerranée".

Âmes sensibles, passez ce chapitre...

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2021/04/16/3115422-63864168-2560-1440.jpg)

Septembre 1975 : Alain Colas sort de l'hôpital après une nouvelle opération.

Je l'avais trouvé en petite forme, fatigué

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2021/04/16/3115514-63866008-2560-1440.jpg)

Alain Colas, Eric Tabarly et Olivier De Kersauson en 1968.

Crédit: Imago

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2021/04/16/3115505-63865828-2560-1440.jpg)

Alain Colas et Eric Tabarly en 1973.

Le pari des Açores, une tactique risquée

Pionnier des consultants sportifs.

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2021/04/16/3115631-63868348-2560-1440.jpg)

Alain Colas, le marin star.

16 novembre, la dernière vacation

Une arrivée de légende avant l'angoisse.

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2021/04/16/3115619-63868108-2560-1440.jpg)

L'invraisemblable arrivée de la Route du Rhum 1978, où Mike Birch s'impose pour à peine une minute trente...

Folles rumeurs

Je souhaite qu'il soit mort le plus rapidement possible...

Où es-tu, Manu-Manureva ?

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2021/04/16/3115419-63864108-2560-1440.jpg)

Plaque en souvenir du marin Alain Colas à Saint-Malo.

Jean Le Cam, le grand homme et la mer

08/12/2021 à 18:45

La suspension d'Escoffier annulée pour vice de procédure

22/03/2024 à 21:14

Soupçons de tricherie : Crémer blanchie par un jury international

04/03/2024 à 14:34

- AI Generator

Alain Colas's 72ft Trimaran "Manureva" moored at Rushcutters Bay after his epic voyage to Australia of 80 days.Manureva, the 68ft trimaran in which Alain Colas sailed single handed from France to Sydney in 79 days.

- Standard editorial rights

- Custom rights

- 1970-1979 ,

- Australia ,

- Black And White ,

- Color Image ,

- Rushcutters Bay ,

- 0 No item in your cart

- SUBSCRIPTION

- Classified Ads

- Technical Specifications

- Destinations

- Address book

- All the magazines

Arkea Ultim Challenge – Brest - Circumnavigating the globe alone, on a giant…

Article published on 31/03/2023

By François Trégouët

published in n°189 may / june

In January 2024, fifty years after the pioneer Alain Colas, the Ultims trimarans will set off for their first solo round-the-world race. A challenge that lives up to its name: the Ultime!

Create a notification for "Offshore racing"

We will keep you posted on new articles on this subject.

On board the latest Ultim trimarans, distances can seem shorter. It was on one of these 105 by 75-foot (32 x 23 m) giants that fly thanks to their foils, that the winner of the last Route du Rhum crossed the Atlantic in just 6 days. However, none of them have ever spent more than seventeen consecutive days at sea. And that was with a crew, on Jules Verne Trophy attempts. All of which were interrupted shortly after the Cape of Good Hope. To date, there are four people who have achieved the feat of sailing solo, non-stop around the planet in a multihull - the current record holder François Gabart, in 42 days, 16 hours and 40 minutes, who overtook the stubborn Thomas Coville (49 days in 2016), the British sailor Ellen MacArthur (71 days in 2005) and finally the legendary Francis Joyon (72 days in 2004). Before them, Alain Colas took 169 days in 1973 to circumnavigate the globe. He certainly made one stopover, but his faithful aluminum trimaran Manureva, formerly Eric Tabarly’s Pen Duick IV, still made history. In 1988, Philippe Monnet improved the time by 40 days despite his two stopovers (in South Africa and New Zealand) on a 60-foot trimaran named Kriter. His record only stood for one year, since Olivier de Kersauson, who also stopped twice (in Cape Town and Mar Del Plata), took only 125 days to return to Brest on Un Autre Regard. All in pink, the very elegant VPLP design built at CDK has become a legend and will remain so for a long time. The 82-foot (25 m) multihull weighed only 23,150 pounds (10.5 tonnes) at the time, compared to the current Ultims’ 33,000 lbs (15 t). To win the Arkéa Ultim Challenge - Brest, you’re going to need a bit of luck... And to have a chance of breaking the record, you’ll need a perfect weather pattern. The start, set for January 7, 2024 at the tip of Brittany, in the heart of winter, could prove to be tough from the outset. As long as it is downwind, it would be ideal to reach the equator quickly. While the passage through the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), better known as the Doldrums, is more pleasant in terms of temperatures, the erratic winds and capricious squalls that characterize this region will test the sailors’ nerves to the limit. The descent, often quite to the west of the South Atlantic, along the Brazilian coast to escape the St. Helena High, is perhaps the least stressful passage, although one must remain vigilant when it comes to choosing the right moment before changing course to the east. Once caught in one of the many lows that circle Antarctica, it is important to stay ahead of it as long as possible, to pass the Cape of Good Hope first, and then then Cape Leeuwin. During a world record race, the sailors are free to choose their route and can cut it as short as possible ...

Subscribe to Multihulls World and get exclusive benefits.

Tags :

- Arkea Ultim Challenge ,

- Ultim ,

- Offshore Racing

Did you like this article ?

Share this article

Most-read articles in the same category.

Who's Who - Nigel Irens: A wonderful, self-taught naval architect

A Wonderful Nautitech Gateway - An Owners’ Meet Up in Martinique

International Multihull Show - The unmissable get-together for multihull fans

The photographer's eye - Rivergate Marina, Brisbane, Australia: Customs Clearance!

2023 Sail Buyer's Guide - Multihulls from 30 to 40 feet

2023 Sail Buyer's Guide - Multihulls from 20 to 30 feet

What readers think.

Post a comment

No comments to show.

Follow us on

Vous avez ajouté " " à vos favoris., vous avez supprimé " " de vos favoris., in order to add this article to your favorites, please sign in..

BoatNews.com

Club Méditerranée: the crazy bet of a 72m sailboat for a single man

Some sailboats have unusual stories. These are legendary boats. This is the case of Club Méditerranée launched for the 1976 Transat. When Alain Colas asked for a 72-metre sailboat to take part in the 1976 transatlantic race, sailors from all over the world laughed in his face. And yet Alain Colas will take up the challenge, in addition to being handicapped at one foot.

When he imagined his next boat after his victory in the 1972 English Transat on his trimaran Manureva, Alain Colas knew exactly what kind of racing machine he wanted. For him, the longer a boat is, the faster it goes. So he wanted the longest boat he could handle.

He met with the naval architect Michel Bigouin (who had already signed the ULDB Pen Duick V) to explain his project. He wanted a boat of more than 60 meters, but with masts of less than 30 meters. Each mast must support a maximum of 120 m2 of sail area. A surface that Alain Colas knows he can still control.

The boat is then designed. She will be 72 m long and will carry 4 masts and more than 1000 m2 of sails in total.

It was then necessary to find a shipyard . At the time, only the Toulon arsenal could produce a 240-ton steel hull within the allotted time. Colas managed to get the doors of this military domain opened.

To finance his boat, Alain Colas relies on Gaston Defferre and his contacts. Very good talker, he manages to make dream the leaders of big companies. Starting with Gilbert Trigano, boss of Club Mediterrenee, who agreed to finance 2/3 of the boat . By making such a financial arrangement, Alain Colas introduced sponsorship into ocean racing for the first time.

The story seems beautiful. In 1975, the dream takes shape. Everything was going well until Pentecost Sunday. In a risky anchoring maneuver on Manureva, Alain Colas had his left foot torn off by his anchor chain in La Trinité-sur-Mer.

22 operations and 5 months later, he visited the shipyard in Toulon leaning on crutches. The various people involved doubted his ability to navigate this enormous boat. However, Alain Colas did not give up and continued to believe in it.

On February 15, 1976, Club Méditerranée was launched and turned around. It's a party! For reasons of too great a draft, the hull was built and launched upside down. Keel towards the sky! The turnaround is carried out once the boat is in the water at the Mourillon slipway.

This boat is incredible. The press is talking about it: it is so well-maintained and operated by one man. Cameras monitor each mast. A hydraulic power plant manages the winches. Behind the chart table, a computer with its screen and printer are even in place. All adjustments can be made without leaving the helm. On the back deck, a wind generator is installed. A lot of equipment developed for this sailboat will be found on board our current pleasure boats.

There were many critics who described this boat as a "button presser". The rather unfair English try to forbid him to take the start of the Transat and ask him to do an additional 1500 mile qualifying run in the Atlantic. Alain Colas came back strutting, announcing that he had not encountered any problemsâ?¦

A devastating race

On June 5, 1976, the Transat started. The race that Alain Colas wanted to win and for which he had built this enormous machine. If the start was made in light winds, the tone quickly changed and the race went through three storms that caused a third of the competitors to abandon.

On Club Mediterranée, the halyards broke one by one. Alain Colas can not iron them alone in the mast. He decided to stop in Newfoundland to repair them. A stop that will last 36 hours. At this stage, he was still in the lead of the race, as there was no news of the other competitors. However, while Colas was expected to arrive in the afternoon, Eric Tabarly on Pen Duick VI emerged from the fog in the early morning to take first place. 7 hours before Alain Colas! The latter had a hard time digesting his defeat. Especially since he was later disqualified by the race committee for having had help at the time of his new departure from Newfoundland.

A charter life for Club Méditerranée

After this race, the Club Méditerranée is fitted out to be operated as a charter. Cabins were built quickly and with little money. At that time, the sponsors left the ship. Unfortunately, a fire broke out while the boat was moored in the port of Marseille , destroying all the work. The boat was then repatriated to Tahiti to continue its charter mission. But Alain Colas was not satisfied with this life. He entered his former trimaran Manureva in the first Route du Rhum in 1978. He would die in this race.

For lack of funds to operate it, Club Méditerranée was abandoned for four years at the bottom of the port of Papeete in Tahiti.

The Tapie adventure

On the advice of Michel Bigouin, Bernard Tapie bought her from the widow of Alain Colas . The yacht was then renamed La Vie Claire and made an attempt at the Atlantic crossing record from New York. Calms at the finish made the attempt fail, but the 24-hour distance record was beaten: 457 miles.

The boat returns to Marseille for a transformation. Bernard Tapie wants to keep the spirit of the fast boat by offering more comfort and luxury. Thus the fittings will remain light even if a longer deckhouse is then installed.

In 1986, after 3 years and 60 million dollars of work, the former Club Méditerranée, renamed Phocéa, was put back in the water. It is mainly used for the leisure activities of its owner and his family.

In 1988, Tapies once again set out to break the record for crossing the Atlantic under sail in a monohull. He beat Charlie Barr's record by 4 days with a crossing of 8 days 3 hours and 29 minutes.

Following legal setbacks with the tax authorities, Bernard Tapie loses the Phocéa which is seized in April 1996.

The transformation of Mouna Ayoub

Put on sale for 71 million francs, it is finally Mouna Ayoub who buys her for 37 million francs. Having become famous after her divorce from Naceur Al Rachid, this businesswoman launched the total transformation of the boat by carrying out a very luxurious refit . No longer looking for performance, the boat was entirely redone with noble (and heavy!) materials. A second floor was even added. The masts are even reduced so that the boat heels less!

Heavier, less canvas, the Phocea has lost all its identity (except its nameâeuros¦). It is proposed to the charter to cover the operating costs.

It was then sold to the owners of Pixmania. The boat finally arrived in Malaysia, visibly abandoned without any understanding of its owners' wishes. The incredible story that sticks to the skin of the "Colas hull" seems to continue, since the boat finally sinks after a fire on February 17, 2021 .

Cruising Forums

- Cruising Forum

- Bosun's Locker

- The Multihull Club

- Living Aboard

- Marine Industry Vendors

- The Poop Deck

CL Yacht Club

- Forum News/Announcements

- Cruiser's Market

Regional Cruising

- Med, Atlantic, Caribbean

- SE Asia, Red Sea, Indian Ocean

- Pacific & Australasia

- General Marine Weather

Message Buoy (Contact)

- General Messages

- Overdue/Distress Reports

- Position Reports

- To Absent Friends

Cruising/Sailing Wiki

- Cruising & Sailing Wiki Discussion

Recent Photos

- Forum Listings

- Register - it's FREE!

- Cruising Crew Wanted

- Crew Positions Wanted

- Miscellaneous

- Autos & Motorcycle

- RV & Travel Trailer

Our Communities

Our communities encompass many different hobbies and interests, but each one is built on friendly, intelligent membership. » More about our Communities

Automotive Communities

Our Automotive communities encompass many different makes and models. From U.S. domestics to European Saloons. » More about our Automotive Communities

RV & Travel Trailer Communities

Our RV & Travel Trailer sites encompasses virtually all types of Recreational Vehicles, from brand-specific to general RV communities. » More about our RV Communities

Marine Communities

Our Marine websites focus on Cruising and Sailing Vessels, including forums and the largest cruising Wiki project on the web today. » More about our Marine Communities

- Mes newsletters

- Mon abonnement

- Lire le magazine numérique

- Aide et contact

- Se déconnecter

Que se passe-t-il avec Jennifer Lopez et Ben Affleck ? On fait le point

Pour leurs 20 ans de mariage, felipe et letizia posent avec leurs princesses, à cannes, carla bruni fait sensation en robe sirène haute couture, il y a 45 ans, alain colas et son manureva perdus à jamais.

ARCHIVES. En 1978, Alain Colas, à bord de son bateau Manureva, disparaissait en mer alors qu'il naviguait en tête de la première édition de la Route du Rhum.

Une liaison radio et puis plus rien... Il y a 45 ans, Alain Colas, à bord de son bateau Manureva, disparaissait en mer alors qu'il naviguait en tête de la première édition de la Route du Rhum. Un marin, une chanson et une légende à jamais. C'est au large des Açores et au coeur de la tempête qu'Alain Colas a dit ses derniers mots, le 16 novembre 1978, après 11 jours de mer: "Je suis dans l'œil du cyclone. Il n'y a plus de ciel, tout est amalgame d'éléments, il y a des montagnes d'eau autour de moi". Alain Colas n'a jamais été retrouvé. Ni son bateau Manureva (qui signifie "Oiseau des îles" en tahitien). Ce drame de la mer a provoqué une émotion si forte que le marin visionnaire est entré dans la légende, lui qui a écrit les premières et belles pages de la course au large française avec son mentor Eric Tabarly, disparu en mer il y a 25 ans. Alain Colas avait 35 ans, une femme et 3 enfants. Teura, sa veuve, vit chaque jour avec cette disparition. Leur fille Vaimiti avait 4 ans quand le navigateur a disparu. Les jumeaux, Tereva et Torea, étaient âgés de 8 mois. Ils ont aujourd'hui 45 ans.

"J'ai vécu si intensément toutes ces années, j'ai fait des dépressions, ça fait partie de ma vie. C'est mon vécu", avait confié Teura Colas à l'AFP. "C'est spécial une disparition en mer, tu ne peux rien faire, tu ne le revois plus". Pour la Tahitienne, "Alain n'est pas mort, Alain a disparu corps et biens". "Les enfants souffrent énormément, ils disent: notre papa c'est un fantôme, on ne veut plus en entendre parler", avait expliqué Teura, qui, dès sa rencontre en 1971 avec Alain Colas, savait qu'il pouvait périr en mer. Mais elle aussi avait des rêves de grand large et comprenait la passion qui animait le navigateur qui n'avait pas peur. "Je lui disais souvent: 'quand tu ne seras plus là, qu'est-ce que je deviendrais ?' Il me répondait: 'tu verras le temps fait bien les choses'. La veille du départ, on s'est aimé pour la dernière fois. Il avait son petit sourire charmant au coin des lèvres", se souvenait Teura. "'Reste heureuse': c'est ce qu'il m'a dit avant de partir à Saint-Malo", avait-elle raconté, avec des grands sourires et des éclats de rire. "C'est un macho-marin-skipper-gentleman. Avec ce côté anglais que j'adorais".

Voici le reportage de Paris Match consacré à la disparition d'Alain Colas en 1978, ainsi que notre rencontre avec Teura, pour son premier Noël sans Alain...

Découvrez Rétro Match, l'actualité à travers les archives de Match...

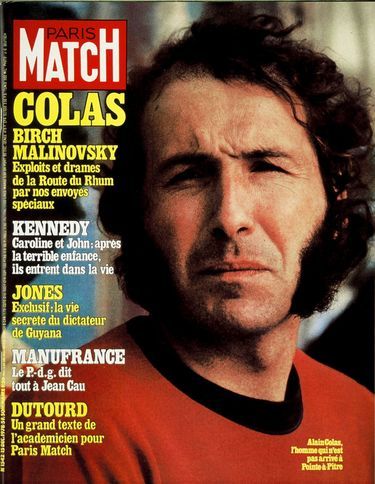

Paris Match n°1542, 15 décembre 1978

Alain Colas, l'Océan lui a refusé sa revanche

par Guy Lagorce

C'était pour lui la course de la dernière chance Depuis son accident atroce survenu en 1975, Colas, après 20 opérations chirurgicales, luttait toujours pour éviter l'amputation de son pied droit devenu complètement insensible. II luttait aussi pour rembourser les dettes contractées après son échec dans la «Transat» 1976. II avait réarmé son bateau géant «Club Méditerranée», un monstre dispendieux de 72 mètres de long pour en faire un voilier de croisière, à bord duquel il convoyait des touristes américains en Polynésie. II luttait aussi pour Teura, une Tahitienne, sa compagne, maman de Vaïmiti et de Tremu et To Rea, deux jumeaux nés au printemps dernier qui ressemblent à leur père. II luttait enfin pour lui, pour redevenir le n°1. Tous les siens étaient venus à Saint- Malo l'encourager de leur présence et de leur affection pour cette course de la revanche et de la dernière chance

C'était le 5 novembre dernier à Saint-Malo. Dans quelques instants Alain Colas, installé dans son cockpit, va s'élancer sur l'Océan à bord de son « Manureva », un trimaran de 20 mètres de long, qui est l'ancien «Pen Duick IV» réaménagé avec lequel en 1972 il était né à la gloire en remportant la Transat en solitaire. Colas est alors confiant en dépit de sa très grave blessure au pied droit qui fait de lui un demi-infirme, car il connaît son trimaran par coeur. En plus de la Transat, il a bouclé deux tours du monde à son bord dont un en solitaire par le cap Horn. Victime du sort contraire, endetté, Alain Colas comptait beaucoup sur cette Route du Rhum pour prendre une revanche sur le destin. Le mauvais sort, encore une fois, s'est acharné sur cet homme de fer. Son absence à l'arrivée à Pointe-à-Pitre a jeté une grande ombre sur une belle course jusque-là heureuse.

Depuis le 16 novembre, depuis que sa radio a cessé d'émettre, on sait qu'Alain Colas grand vainqueur de la Transat en 1972, a perdu son formidable pari : redevenir malgré son infirmité le meilleur navigateur du monde. Aussi belle qu'elle ait été, cette Course du Rhum vers la Guadeloupe gardera le goût amer de l'angoisse, de l'atroce attente.

L'absence à Pointe-à- Pitre d'Alain Colas, héros de notre temps, étend une grande ombre sur cette aventure de mer, de solitude et de soleil. Du danger qu'il y a à courir les mers en solitaire, Colas avait dit un jour : « De même qu'en automobile le bon pilote de formule 1 est celui qui laisse la plus faible marge au hasard, le bon navigateur est celui qui aura su le mieux armer son bateau en fonction de la course et qui aura assez de sang-froid et de technique pour naviguer au plus juste. Cela dit, le danger existe toujours. Le bonheur dans la vie est de faire ce que l'on a envie de faire. Le faire sans regrets et ne jamais se retourner sur ses pas. Je ne conçois pas la vie autrement...» Le voilà bien le romantisme. Le vrai.

C'est en 1972 que Colas naît à la gloire. La nouvelle embrase toutes les «Une» des journaux du monde : huit ans après Eric Tabarly, un autre Français - et quel personnage ! - vient de gagner la «Transat », la course la plus célèbre et la plus rigoureuse du monde. II n'est pas alors de trompettes assez puissantes pour sonner la renommée de ce mince jeune homme de 29 ans, ancien coéquipier de Tabarly auquel, pour réussir son exploit, il a racheté le fameux trimaran « Pen Duick IV ». Puis, peu à peu, le silence se fait autour de Colas. II agace. On le trouve un peu trop brillant dans le monde alors volontiers taciturne des coureurs des mers. En fait, ce licencié ès-lettres n'a besoin de personne pour se faire entendre : ses conférences, ses films, son livre, il les faits seul. II parle haut et fort. Et puis ce terrien né à Clamecy, dans la Nièvre, très loin de la mer, a tout appris tellement vite… «Trop vite » disent les marins qui ne comprennent guère cette âme brûlante et vive. Pour eux, Alain Colas c'est le «barbare».

En 1965, à l'âge de 21 ans, il part pour l'Australie. Pour payer son voyage, il travaille sur un cargo et se fait embaucher comme professeur à l'université de Sydney. «J'avais envie d'être autre. Mon père, ouvrier tourneur, est devenu le patron d'une faïencerie à force de volonté. Son exemple m'a marqué. Comme lui, je voulais sortir de ma peau. De ma chambre, je voyais la baie de Sydney, une splendeur qui, durant le week-end, devenait un mur de voiles. Alors, comme je ne tenais pas en place, j'ai réussi à me faire embarquer, pour voir. C'est alors, mais alors seulement, que j'ai eu le coup de foudre pour la mer. J'avais 22 ans. »

Dès lors, tout ira très vite. Colas devient en quelques mois un as de la régate. Aussitôt, il brûle d'impatience, il veut déjà prendre le large. Signe du destin, Tabarly fait escale à Sydney et cherche des équipiers. Colas embarque avec lui pour la course Sydney-Hobart et, d'entrée de jeu, essuie son premier cyclone. II apprend à vivre ce qui va devenir sa vie. En 1968, Colas veut revenir en France, passer d'autres examens pour devenir traducteur. II arrive à Paris en mai 1968. «Je débarquais du bout du monde, j’ai été incapable de m'intéresser à ce qui se passait en France. Ça me paraissait être une tempête dans un verre d'eau. Moi, je me sentais citoyen du monde alors... je suis parti retrouver Tabarly et la mer pour toujours. »

La suite, on la connaît : traversée de l'Atlantique, et la course San Francisco - Honolulu - Los Angeles - Tahiti. Puis c'est l'achat du « Pen Duick IV », la victoire dans la Transat, le tour du monde, la gloire. Le licencié Alain Colas est devenu l'agrégé de la voile, le maître fulgurant.

L'astre Colas est à son zénith. II va brutalement décliner. Le 19 mai 1975, c'est l'imbécile et horrible accident: une chaîne d'ancre s'enroule autour de sa cheville droite. Son pied au bout de la jambe ne tient plus que par les tendons. Colas refuse l'amputation et reste six mois à l'hôpital de Nantes où il subit 20 interventions chirurgicales. II endure un martyre et participe quand même à la Transat 1976. Il est battu par Tabarly avec lequel ses rapports se sont dégradés. Fatigué et amer, son pied nécessitant des soins constants, Colas croule sous les dettes, car il a vu très grand. Trop grand. Pour rentabiliser son monstrueux bateau (72 mètres de long, 10 millions de francs), le «Club Méditerranée», il commande des travaux à Marseille. Ils seront très lourds. En outre, le 26 septembre 1977, le bateau est victime d'un grave incendie qui détruit la timonerie. On se demande alors s'il s'agit d'un acte criminel de plus dans la série d'attentats qui frappe cet été-là tout ce qui porte le nom de Club Méditerranée.

C'est la série noire. Quatre mois plus tard, tout est réparé, le bateau est transformé ; la bête de course est devenue un animal domestique apte aux promenades en mer, apte à gagner de l'argent à défaut de courses et de rêves...