How to Say Sailboat in Japanese

- Sagittarius

- improvisation

- misrepresent

What is "Sailing" in Japanese and how to say it?

More sports vocabulary in japanese, example sentences, "sailing" in 45 more languages., other interesting topics in japanese, ready to learn japanese, language drops is a fun, visual language learning app. learn japanese free today..

- Drops for Business

- Visual Dictionary (Word Drops)

- Recommended Resources

- Redeem Gift

- Join Our Translator Team

- Help and FAQ

Drops Courses

How to say sailboat in Japanese

- sailboat ; sailing boat

Example Sentences

© Based on JMdict , KANJIDIC2 , and JMnedict , property of the Electronic Dictionary Research and Development Group , used in conformance with the Group's licence . Example sentences from the Tatoeba project (CC BY 2.0). Kanji stroke order data from the KanjiVG project by Ulrich Apel (CC BY-SA 3.0). See comprehensive list of data sources for more info.

Translation of "sailboat" into Japanese

帆船, ヨット, 帆前船 are the top translations of "sailboat" into Japanese. Sample translated sentence: He started his voyage around the world in his sailboat. ↔ 彼はヨットで世界をまわる航海を始めた。

(slang) a playing card with the rank of four [..]

English-Japanese dictionary

a boat propelled by a sail [..]

In April 2012, a group of publishers traveled by sailboat to Polowat, one of the most isolated islands.

2012年4月,奉仕者たちの一行が孤立した島の一つポロワット島に 帆船 で向かいました。

He started his voyage around the world in his sailboat .

彼は ヨット で世界をまわる航海を始めた。

Less frequent translations

Show algorithmically generated translations

Automatic translations of " sailboat " into Japanese

Translations with alternative spelling

"Sailboat" in English - Japanese dictionary

Currently we have no translations for Sailboat in the dictionary, maybe you can add one? Make sure to check automatic translation, translation memory or indirect translations.

Images with "sailboat"

Phrases similar to "sailboat" with translations into japanese.

- Western style sailboat ふうはんせん · 風帆船

- solitary sailboat こはん · 孤帆

- motorized sailboat きはんせん · 機帆船

- motorised sailboat きはんせん · 機帆船

- returning sailboat きはん · 帰帆

Translations of "sailboat" into Japanese in sentences, translation memory

Translation of “sailboat” in Japanese

Word of the day: meet · 会う

Browse by Letter

Use our dictionary's search form to translate English to Japanese and translate Japanese to English.

"more translation" means that there is more than one translation.

- ABBREVIATIONS

- BIOGRAPHIES

- CALCULATORS

- CONVERSIONS

- DEFINITIONS

Vocabulary

Translations

How to say sailboat in japanese ˈseɪlˌboʊt sail·boat, would you like to know how to translate sailboat to japanese this page provides all possible translations of the word sailboat in the japanese language..

- 帆船 Japanese

Discuss this sailboat English translation with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe. If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

You need to be logged in to favorite .

Create a new account.

Your name: * Required

Your email address: * Required

Pick a user name: * Required

Username: * Required

Password: * Required

Forgot your password? Retrieve it

Citation

Use the citation below to add this definition to your bibliography:.

Style: MLA Chicago APA

"sailboat." Definitions.net. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 30 Mar. 2024. < https://www.definitions.net/translate/sailboat/EN >.

The Web's Largest Resource for

Definitions & translations, a member of the stands4 network, free, no signup required :, add to chrome, add to firefox, browse definitions.net, are you a words master, make more complex, intricate, or richer, Nearby & related entries:.

- sailboarder

- sailboarding

- sailboat noun

- sailboating

- sailcloth noun

Alternative searches for sailboat :

- Search for sailboat on Amazon

Master the Word: How to Say Boat in Japanese – A Quick Guide

Are you interested in learning how to say “boat” in Japanese? Look no further! This comprehensive guide will teach you everything you need to know about the Japanese word for “boat,” including its translation and meaning, pronunciation, and cultural significance.

Whether you’re a beginner or an advanced Japanese learner, mastering transportation vocabulary is essential. In this guide, we’ll cover basic and advanced vocabulary related to boats, providing you with a well-rounded understanding of the topic.

So, let’s dive in and begin our journey towards mastering the word for “boat” in Japanese. By the end of this guide, you’ll have the knowledge and confidence to incorporate this word into your Japanese language skills seamlessly. Let’s get started!

Introduction to Japanese Vocabulary

Before we dive into the specific word for “boat” in Japanese, it’s important to understand the structure of Japanese vocabulary and how new words are formed. Like many other languages, Japanese has a combination of native and borrowed words. Native words are called “yamato kotoba” and make up the majority of everyday language, while borrowed words are called “gairaigo” and come from other languages, primarily English.

Japanese is also known for its use of kanji, which are Chinese characters that have been adapted for the Japanese language. Kanji are combined with two other phonetic scripts: hiragana and katakana. Hiragana is used for native Japanese words and verb endings, while katakana is primarily used for borrowed words.

Now, let’s apply this knowledge to the word for “boat” in Japanese.

The Japanese word for “boat” is written as “船” in kanji, and pronounced as “funa.” This word is classified as a noun, which means it is used to refer to a person, place, thing, or idea.

Now that we have a basic understanding of Japanese vocabulary , let’s move on to some basic Japanese words related to transportation, including boats.

Basic Japanese Words for Transportation

When it comes to communicating effectively in Japanese, it’s important to have a solid grasp of vocabulary related to transportation. In this section, we’ll introduce you to some basic Japanese words for various modes of transportation, including cars, trains, planes, and boats.

As you can see, the Japanese word for “boat” is “fune”. This is the word you’ll use when you want to talk specifically about boats, whether it’s a small fishing boat or a large cruise ship.

It’s worth noting that the word “fune” can also have other meanings in different contexts. For example, it can sometimes be used to refer to a ship or vessel in general, rather than a specific type of boat.

Learning these basic transportation words will help you understand the nuances of Japanese vocabulary related to boats and transportation, and make it easier to incorporate the word for “boat” into your conversations.

The Word for Boat in Japanese

Now that we’ve explored the basics of Japanese vocabulary and transportation, it’s time to dive into the word for “boat” in Japanese. The word for “boat” in Japanese is “船” (fune).

The word “fune” is a versatile word that can refer to a variety of different types of boats, including traditional fishing boats and modern-day luxury yachts. It’s a commonly used word in everyday conversations and is a must-know word for anyone interested in Japanese culture and language.

In addition to its literal meaning of “boat,” “fune” also has cultural and symbolic significance in Japanese culture. Historically, boats have played an important role in Japanese society, from fishing and transportation to military and cultural activities. Therefore, the word “fune” may evoke a variety of meanings and associations depending on the context in which it’s used.

When pronouncing “fune” in Japanese, it’s crucial to emphasize the second syllable. The vowel sound in the first syllable should be relatively short, while the vowel sound in the second syllable should be elongated. This will help ensure that you’re pronouncing the word correctly and that others can understand you clearly.

Now that you know the Japanese word for “boat,” it’s time to practice using it in conversations. In the next section, we’ll provide you with some practical examples and phrases involving the word “fune.”

Using the Word for Boat in Conversations

Now that you’ve learned the Japanese word for boat and its pronunciation, it’s time to practice using it in conversations. Here are some practical examples:

As you practice using the word for boat in conversations, pay attention to the pronunciation and intonation. Remember to use proper particles and verb tenses to convey your intended meaning accurately.

Another excellent way to improve your Japanese language skills is by watching Japanese movies and TV shows that feature boats or sailing. You can also read Japanese literature or news articles that discuss boats or water transport. This exposure will help you build your vocabulary and cultural knowledge, making you a more fluent and confident speaker.

By following this guide, you should now have a good understanding of how to say “boat” in Japanese. Remember that language learning is a gradual process that requires time and dedication, so don’t get discouraged if you don’t master it all at once. Keep practicing, and you’ll soon be able to have nuanced conversations about boats in Japanese.

Advanced Vocabulary Related to Boats

Now that you have a solid understanding of the basic word for “boat” in Japanese, it’s time to expand your vocabulary further. Below are some advanced Japanese words related to boats:

By adding these words to your vocabulary, you’ll be able to have more nuanced conversations about different types of boats, boating activities, and nautical terms. Practice using them in context to master their usage.

Cultural Significance of Boats in Japan

Boats have played a significant role in Japanese culture for centuries. They were not only a means of transportation and fishing but also important symbols of religious and cultural significance.

One of the most famous boat festivals in Japan is the Gion Matsuri in Kyoto. During this festival, a large wooden boat called “Hoko” is paraded through the streets, accompanied by musicians and dancers. This boat is adorned with intricate traditional decorations and symbolizes the power and wealth of the community.

In Japanese art and literature, boats are often depicted as symbols of journey and transition. This is particularly evident in haiku poetry, where boats are a common motif. They represent the fleeting and transitory nature of life and its constant changes.

Boats also have historical importance in Japan. During the Edo period (1603-1867), the government established a system of official boats to transport goods and people between different regions. These boats were heavily guarded and contributed to the development of Japan’s commercial and cultural exchange.

Overall, boats hold a special place in Japanese culture, and their symbolism and significance continue to inspire and fascinate people around the world.

Conclusion and Final Thoughts

Learning a new language can be a challenging yet exciting experience. We hope that this guide has helped you master the Japanese word for “boat” and provided you with a deeper understanding of its usage and cultural significance.

Remember, practice makes perfect. Don’t be afraid to use this new vocabulary in conversations and continue expanding your Japanese language skills. And if you’re interested in learning more advanced vocabulary related to boats or exploring the cultural context of boats in Japan, there are plenty of resources available to help you.

With this guide, you now know how to say “boat” in Japanese, the Japanese word for “boat,” its translation and meaning, and how to use it in conversations. Keep in mind that “boat” is just one word in the vast world of Japanese vocabulary, and there’s always more to explore and learn.

Thank you for joining us on this language journey. We wish you the best of luck in your Japanese language studies!

Q: Can you provide a literal translation of the word for “boat” in Japanese?

A: The word for “boat” in Japanese is “船” (fune). However, it’s important to note that the translation of a word doesn’t always capture its complete meaning and cultural connotations.

Q: How do you pronounce the word for “boat” in Japanese?

A: The word “船” (fune) is pronounced as “foo-neh” in English. The “u” is silent, and the “ne” has a short “e” sound.

Q: Are there any other meanings associated with the word for “boat” in Japanese?

A: Yes, the word “船” (fune) can also mean “ship” in addition to “boat.” The specific meaning can depend on the context in which it is used.

Q: Can you provide some example sentences using the word for “boat” in Japanese?

A: Sure! Here are a few examples: – 私は船で海に行きました。(Watashi wa fune de umi ni ikimashita.) – I went to the sea by boat. – あの船はとても大きいですね。(Ano fune wa totemo ookii desu ne.) – That boat is very big, isn’t it? – 船で川を旅するのは楽しいです。(Fune de kawa o tabi suru no wa tanoshii desu.) – Traveling by boat on a river is fun.

Q: Are there any specific cultural traditions or festivals in Japan involving boats?

A: Yes, Japan has several boat-related cultural traditions and festivals. One notable example is the “Toba Shinmei Shrine Annual Festival,” where locals decorate boats and participate in a procession on the water. Another famous event is the “Nagasaki Kunchi Festival,” which features street parades and boat races. These festivals showcase the cultural significance of boats in Japan.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Japanese Sailboat Brands

Last Updated by

Jacob Collier

August 30, 2022

Many Japanese boats are considered among the best in the business. If you are thinking about the best Japanese sailboat brands, you’re in the right place.

Japan is no stranger to the world of sailing. When it comes to investing in a sailboat, you might want to consider Japanese sailboat brands because their boats offer just the right mix of technology and ergonomic design, which is what sailing enthusiasts look for in boats.

From Mitsubishi to Ishikawajima-Harima, and Yamaha, there are many Japanese brands that are making a mark in the sailboat industry. These sailboats range from compact beginner vessels to luxury yachts for more experienced sailors.

Many Japanese brands produce a range of reliable boats for sailing newbies, as well as experts that can make the sailing experience comfortable and fun.

As sailing enthusiasts who have owned and sailed in many different types of sailboats, including Japanese sailboats, we are in the ideal position to help you make a more informed decision when it comes to choosing from Japanese sailboat brands.

Table of contents

Japanese Sailboat Brands

There's no disputing that sailors are passionate individuals. They are so enthusiastic about sailboats that they’re always on the lookout to find the greatest ones. Many sailing enthusiasts fantasize about owning a sailboat, but few of us ever have the opportunity to cruise the seas on something we can truly call our own. While you can rent a sailboat, many sailors aspire to purchase one.

Gliding over the ocean, waves, and wind in the company of a beautifully made sailboat provides an unparalleled sense of comfort and calm. When you combine this with the fact that sailing takes you far away from the everyday grind that we've grown accustomed to, it's easy to see why sailing is so enticing to the people. However, without a decent sailboat, all of this enjoyment and the pleasures of sailing are lost.

Contrary to popular belief, buying a sailboat is not out of reach for everybody. It's something we can all accomplish. But, first, it's vital to understand some of the greatest sailboat brands. The greatest sailboat brands can make your sailing life smoother and more enjoyable. The top sailboat brands have perfected the skill of carpentry for decades, if not centuries.

What makes Japanese sailboat brands unique is that they've committed their abilities and a significant amount of time to developing and constructing the highest quality sailboats available. You've come to the correct place if you're seeking the top sailboat brands from around the world. We'll talk about the best options in Japanese sailboats, something that will provide you with a fantastic escape from your daily routine.

Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Ind. Yachts

Yachts are constructed in Japan by Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries. The shipyard has produced superyachts up to 77 meters long and 2200 tons, with an average of 56 meters long and 787 tons. The company Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Ind. launched a total of 5 superyachts and is showing no signs of slowing down any time soon.

IHI Corporation is a heavy-industry producer with four primary areas of focus: resource, energy, the environment, and defense. But, it has also garnered a reputation for its luxury yachts. IHI's origins date back to 1853, when the Ishikawajima Shipyard, Japan's first modern shipbuilding plant, was founded.

The firm was instrumental in Japan's modernization, utilizing its shipbuilding expertise in new fields, including plant construction, aero-engines, and heavy machinery manufacturing. Ishikawajima Heavy Industries joined Harima Shipbuilding & Engineering to become Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries in 1960, the successor of Ishikawajima Shipyard. In 2007, the name IHI Corporation was chosen to promote the company's worldwide brand.

IHI is dedicated to making a positive impact on society via technology, integrating a wide range of engineering skills to fulfill the growing worldwide need for energy, urbanization and industrialization, and transportation efficiency.

One of the standout yachts of the company includes the Paloma. The luxury yacht is an incredible feat in yacht design; the vessel was built in 1965 at the Ishikawajima-Harima shipyard in Japan and measured 60.25m (197' 8"). The yacht was completely rebuilt in Malta in 2003-04 to the Owner's specifications.

The luxury yacht features some great amenities, such as comfy furniture and decor, a/v entertainment system, water sports equipment, a luxury on-deck Jacuzzi, and anchor stabilizers for a smooth stay aboard the luxury yacht.

During Paloma's renovation, she acquired new onboard systems as well as the majority of her interior and external equipment, including an entirely new engine room with cutting-edge engineering equipment and cutting-edge navigation and communication systems.

The interior décor is subtle modern English style, with a blend of rich, colorful materials complimented by her original wood paneling that adds to the warm and inviting environment. The main salon of the classic yacht Paloma is spacious, with many comfortable seating places, a wide sofa, bar facilities, an office room, and a giant Plasma screen television.

The formal dining space, which can be closed off, is located forward of the main salon. A plasma TV and music equipment are installed in an audio/visual recreation room placed ahead of the eating area. Paloma is a classic yacht with a large main deck, which is part of its aesthetic appeal and is the reason why Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Ind, makes it one of the biggest names in the yacht world.

New Japan Yachts

New Japan Boat was founded in 1969 in Shirai, Makinohara City, Shizuoka Prefecture, and is currently one of the few domestic yacht builders. The company used to solely make yachts but expanded into the RV / camper sector, which has a lot in common with yachts. They've started doing interior work and selling components for campers, particularly outfitted cars.

Requests for different FRP-related items, such as FRP sinks, custom-made products, and shells for mobile sales vehicles, are also accepted by the company. The Libeccio is their best-selling yacht. Libeccio, a 26ft class representative boat, is a best-selling true cruising yacht capable of running in open waters.

The Group Fino design provides a superb combination of stability, operability, usefulness, and comfort that never gets old. A strong hull that has sailed the seas of Japan and a serene cabin made of teak. The most crucial but frequently overlooked subject once you leave the port is returning to the port. The company has solved this problem with its modern design and features.

Libeccio's hull stability is designed to provide high stability and sailing performance without adding additional weight. It is a critical feature that eliminates the anxiety of running in heavy winds while also reducing occupant fatigue. NJY's dedication to "hand lay-up" creates the hull by stacking without omissions. The hull liner is, of course, fully attached to the interior of the integrally molded hull.

It is one of the strongest hulls ever made, designed to withstand the worst sea conditions. The same manufacturing procedure is used for all NJY boats. The ability to quickly convert a small place to its intended purpose. This is a key consideration in this class and is what sets them apart as yacht builders. It is adjusted for optimum usage in any environment, from the living area to a navigation room, dining room to a luxurious bedroom.

Aoki Yacht is another big name in the world of Japanese sailboat building. The sailboat builder is known for its design of the Zen24, which is a class apart. The inspiration behind the design is clear, which is that it’s important to practice sailing with a single hand for a long period in order to develop your sailing skills. In 500 hours, a little difference in wind level may be noticed, and in 1000 hours, blind sailing is conceivable. Zen24 is a semi-custom sailing vessel, which makes that possible.

You may mix and match the fittings, equipment, and even the interior finish to suit your riding style. There are three standard kinds. To ensure a long life, an ISO-based weather-resistant polyester resin is employed, and a UV blocking layer is produced under the gel coat. The essential keel mounting portion is attached to the inner hull using a sturdy fastening mechanism. The firm has a dependable and straightforward fitting out to improve your sailing. The engine is capable.

Outboard motors and diesel inboard motors are all options for the powerplant. You'll feel fantastic while sailing alone on a yacht that is so quiet that you could go unnoticed. However, not only for skippers but also for convenient equipment, rapid weather changes might be a difficulty. When the weather suddenly changes, the captain runs out of room and mishandles the equipment. The halyard that goes to the cockpit is prone to errors. A single blunder sets off a chain reaction.

In this sense, the ocean's reality frequently falls short of expectations, so you will need the right boat for the job. Even if you are only sailing for the day, you may experience unexpected weather changes. It is safer to plan for unexpected weather changes, which is easy to do on this luxury yacht because of the many modern features that make it easy to navigate.

Complex fittings stymie the sailors’ ability to control the vessel, which is why this boat is extremely easy to use and maneuver. This is due to the fact that the reading of the wind and tides is updated in real-time, so you are not distracted while navigating. This is exactly what a skipper needs; it is a strategy that allows the boat to function at its optimum by employing basic fitting out to observe sails, wind, and currents, which the Zen24 allows sailors to do effortlessly.

Nishii Zosen KK/Sterling Yachts

The motor yacht Lady Orient is a 48-meter (158-foot) large carbon ship designed by Sterling Scott and built by Nishii Zosen Kk/Sterling Yachts. The motor yacht Lady Orient, which can accommodate 20 guests and 13 professional crew, was previously known as 687 Lady Kinara; her build project name, or yacht title was Asean Lady.

The naval architect engaged in the formal vessel composition for Lady Orient was Sterling Scott. Sterling Scott was also involved in the basic design work for this yacht. This boat was built by Nishii Zosen Kk/Sterling Yachts in the well-known yacht-building country of Japan. Before being given to the owner, she was successfully launched at Ise in 1983.

A total beam (width) of 8.23 m or 27 ft creates an impression of spaciousness. She is quite shallow, with a maximum depth of 2.74m (9ft). The hull of the motorboat was constructed using the material carbon. Carbon fiber is used to construct her superstructure above the hull.

Lady Orient can attain a top speed of 16 knots thanks to two Caterpillar diesel main engines. Twin-screw propellers are connected to the engines. Her overall HP is 2110, and she has 1553 Kilowatts. She uses Naiad as a stabilizer. The Lady Orient was built to accommodate up to 20 people. This ship can accommodate up to 13 passengers. This ship can accommodate up to 13 capable crew members, allowing for a relaxing luxury yacht holiday experience.

The luxury yacht Devotion was completed in 1986 at the Nishii Zosen Kk/Sterling yard and is 43.6 meters (143 feet) in length. As a result, she was proudly manufactured in Japan. Her former names were 688 Shalimar, Lindeza, and Marjorie Morningstar (s). Bannenberg Designs Ltd created an elegant external style. Sterling Scott created the naval architect design for the warship. The interior design was created by Arthur Fishman (1986) and Susan Puleo (1990). The superyacht hull was constructed using composite material, which makes the vessel more ergonomic.

The draught is 2.59 meters (8.5 feet), and the beam is 7.92 meters (26 feet). The superstructure is mostly composite up top. With a cruising speed of roughly 14 knots, Devotion has a range of over 2500 nautical miles under typical weather conditions. Her whole range is powered by her 60500-liter fuel capacity. The maximum number of visitors allowed at Devotion is nine. The boat can also accommodate up to 8 yacht crew members, ensuring a relaxing luxury yacht holiday.

Horizon Group

Horizon Group is the first Asian yacht manufacturer to use four separate subsidiary shipyards to manufacture its premium boats. Each yard adds a specific technique to the development, allowing for not just higher capacity but also a more efficient build operation overall, according to Horizon Group CEO John Lu's design. The shipyards may integrate and grow on each other's ideas and resources under Lu's group structure while emphasizing the spirit of artisanship.

Horizon is distinguished from other yacht builders by its flexibility in design and construction, which allows each boat to be modified to fit the unique owner's lifestyle. Horizon's devoted staff of highly experienced professionals makes this degree of personalization feasible. Horizon's specialized staff of highly competent yacht-building professionals would not be able to provide this level of personalization.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries has designed and built many luxury yachts over the years. Dubai Shadow was once known as Umitaka Maru's project/yacht Australis Mentor. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries built this 79-meter (259-foot) luxury yacht in 1973. The superyacht Dubai Shadow is a stunning vessel. Mitsubishi Hi is the naval architectural business that created the yacht's blueprints and overall arrangement.

Dubai Shadow is the support boat for the luxury superyacht, which was previously the world's largest superyacht. Dubai Shadow is a powerful and durable vessel meant to transport all of the extras that do not fit aboard Dubai, such as tenders, speed boats, toys, jet skis, and fishing and diving equipment. The Dubai Shadow also serves as a support vessel for additional supplies and lodging.

Mitsubishi Hi was the naval architect for Dubai Shadow's official superyacht design work. This project was also completed successfully by Mitsubishi Hi. She was officially launched in Shimonoseki in 1973, and after sea testing and final completion, she was handed over to the owner who commissioned her.

In Japan, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries completed the construction of a new motorboat. Steel was used to make the hull. The superstructure of a motor yacht is mostly built of steel. Dubai Shadow has an amazing interior capacity with a width of 12.4 meters (40.7 feet).

She has a 5.35m draught, which is rather deep (17.55ft). By 2006, she had completed refit improvements and modifications. A single screw propeller propels the Dubai Shadow. The yacht's primary engine produces 3304 horsepower (or 2475 kilowatts).

Hitachi Zosen Corp.

Hitachi Zosen Corporation is a major industrial and engineering corporation founded in 1881 in Osaka, Japan. The company has also been recognized for its sailboat designs, such as the company’s signature design, the yacht Mikado.

The sailing yacht Mikado is a 47-meter-long, 155-foot-long aluminum boat designed by William Garden and Martin Francis and built from the keel up by Hitachi Zosen rp. A spacious ketch motor sailer is a particularly unusual Japan-built superyacht that was launched to great acclaim in 1986. William Garden and Martin Francis were the naval architects that created the design for this ship. Parish-Hadley is also responsible for interior design. She is a ketch motor sailer in the conventional sense.

The naval architectural firm William Garden was engaged in Mikado's technical superyacht design. Parish-Hadley was in charge of her interior design. The boat design is also linked to William Garden and Martin Francis. William Garden and Martin Francis are also involved in the yacht's overall design partnership.

The yacht was designed and built in Japan by Hitachi Zosen rp. Before being given to the owner, she was successfully launched at Kanagawa in 1986. Aluminum was used for the primary hull, making the boat lighter. The superstructure of a sailing boat is mostly built of aluminum. Mikado is rather huge, with a width of 9.51 meters (31.2 ft). Her draught is 6.34 meters (20.8 feet) (20.8ft). In 2008, she had refit improvements and alterations made.

Mikado has been designed to reach a top speed of 12 knots thanks to twin GM diesel engines. Twin-screw propellers power her propulsion system. In addition, she has a driving range of 3000 miles. When traveling at her cruise speed of 11 knots, she has a range of 3000 miles. Her total HP is 972, and she has 715 Kilowatts. Vosper is her go-to stabilizer.

Kanawa Shipyard

The Kanawa Shipyard also has quite a few luxury yacht designs under its belt mainly because of collaborations with other world-renowned yacht designers. One such design is the Don Giovanni, a superyacht designed by the company in 1964.

The superyacht Don Giovanni can accommodate up to 6 guests along with a total of four crew members. Her rather conventional interior design was christened in the year 1964 and exemplifies the typical yacht setting from A Pistoia / S Caracci (Refit), which are the leaders in interior yacht design.

Kanagawa was the naval architect company in charge of Don Giovanni's technical superyacht design. Kanagawa was also a successful collaborator on this project. The general inside styling was chosen by interior designer A Pistoia / S Caracci (Refit).

She was successfully launched in Kobe in 1964, and after sea testing and final completion, she was transferred to the yacht owner. In Japan, Kanagawa Shipyard constructed a new-build motorboat. With a total beam (width) of 7.85 m or 25.75 ft, the sensation is adequate. Steel was utilized to construct the hull of the motorboat. Steel is used to construct her superstructure above deck. In 2009, more refit and upgrading work was completed.

The boat is powered by a nippon hatsudaku compressed air start engine. Twin-screw propellers propel her sheathed in skirts that double as the vessel’s rudders. The yacht's engine produces 1000 horsepower (or 783 kilowatts).

Yamaha Motors

Yamaha Motors was founded in 1955 in Japan. While the company is known for its motorcycles and other vehicles, including outboard motors, they have also made a name in the boating industry. Since its inception more than 50 years ago, the Yamaha Motor Group has been dedicated to the production of different values via manufacturing and services.

The Yamaha Motor Group is a firm that uses wisdom and enthusiasm to achieve people's ambitions, with the goal of offering fresh feelings and prosperous lifestyles to people all over the world, and is constantly expected to be "the next impression." It is clear that they want to be known as an amazing creative firm.

Yamaha has always strived to be a company that is new and impresses by offering new value. They have built unique goods and a wide range of products using a mix of energy and four main technologies: body/hull technology, control technology, and powertrain, just to name a few. The firm has expanded through expanding our business and creating demand for ourselves.

The electrification of mobility, the rapid growth of digital technology, and the rearrangement of numerous frameworks that follow it are all big developments in business trends. Under such conditions, modern technology, a diverse set of business foundations, and the capacity to mold ideas and concepts will be important driving forces.

Related Articles

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

Born into a family of sailing enthusiasts, words like “ballast” and “jibing” were often a part of dinner conversations. These days Jacob sails a Hallberg-Rassy 44, having covered almost 6000 NM. While he’s made several voyages, his favorite one is the trip from California to Hawaii as it was his first fully independent voyage.

by this author

Best Sailboats

Most Recent

Affordable Sailboats You Can Build at Home

Daniel Wade

September 13, 2023

Best Small Sailboats With Standing Headroom

December 28, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

Best Bluewater Sailboats Under $50K

Best Blue Water Sailboats Under 40 Feet

Which Sailboats Have Lead Keels?

June 20, 2023

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

June 15, 2022

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Get the best sailing content.

Top Rated Posts

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies. (866) 342-SAIL

© 2024 Life of Sailing Email: [email protected] Address: 11816 Inwood Rd #3024 Dallas, TX 75244 Disclaimer Privacy Policy

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Translation of boat – English–Japanese dictionary

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

(Translation of boat from the Cambridge English–Japanese Dictionary © Cambridge University Press)

Translation of boat | GLOBAL English–Japanese Dictionary

(Translation of boat from the GLOBAL English-Japanese Dictionary © 2022 K Dictionaries Ltd)

Examples of boat

Translations of boat.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

Hippocratic oath

a promise made by people when they become doctors to do everything possible to help their patients and to have high moral standards in their work

Sitting on the fence (Newspaper idioms)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English–Japanese Noun

- GLOBAL English–Japanese Noun

- Translations

- All translations

Add boat to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- Annual Conference March 14-17, 2024

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

Japanese wooden boatbuilding: history and traditions.

In Western maritime histories, Japan is not generally viewed as a major maritime power. The usual standards for preeminence in this regard have been measured by the reach of a country’s exploration and trade or naval might. Japan’s problem is largely one of timing. It did not become a naval power until the twentieth century, and most Western scholars have interpreted Japan’s maritime importance in light of its reclusiveness—a perception magnified by the timing of European contact. The West’s great era of exploration encircled the globe just as Japan entered its famous 250-year period of exclusion—known as the Edo era—in which foreign travel by Japanese was banned, and contact with most foreigners, especially Europeans (except for the Dutch), was strictly controlled. It has often been written that to enforce these restrictions, Japanese shipwrights were required to build vessels that were inherently unseaworthy, yet another blow to Japan’s maritime reputation. They were never intended to sail out of sight of Japan’s shores. Instead, they sailed through a political and martime era that looked primarily inward, ignoring the horizon. (1)

Japan was an important maritime power in Asia before the Edo era, and even after the era began, for the first few decades of the seventeenth century as a major exporter of silver and copper. Although the Tokugawa shogunate did begin to adopt laws restricting sailing vessels from foreign voyages, there were no actual shipbuilding restrictions. Japanese vessels had, before that time, carried on extensive trade with the Ryūkyū Kingdom (modern- day Okinawa and other islands in the chain) and kingdoms in present-day Korea, China, Thailand, and Việt Nam. The ships that carried out this trade reflected technological influences from Japan’s Asian neighbors, as well as the influence of the Portuguese and Dutch, who had been sailing to Japan since 1543.

A series of edicts restricting trade, Catholic missionaries, and merchants known collectively as Sakoku between 1635 and 1639 eventually resulted in an official ban on all foreign travel by Japanese. Strictly controlled trade contacts with the Dutch, Koreans, Chinese, and Ainu (Japan’s aboriginal population, living mainly in Hokkaidō) were established, but Japan’s own European maritime trade with powers other than the Dutch was banned, and its Southeast Asian trade was only rarely allowed.

Japan’s geography, however, would ensure that the country would necessarily maintain and develop its ship and boatbuilding traditions. The Japanese archipelago is essentially a line of mountains with a relatively limited amount of arable land around the margins. Traveling through the country was difficult, but a few major rivers and Japan’s inland waters offered alternative trade routes to the steep slopes and thick forests of the interior. Furthermore, in seeking to limit the military power of its vassals, the shogunate placed restrictions on the use of carriages and the construction of large bridges. The seas surrounding Japan were the most viable highway for goods, and therefore, the maritime history of the Edo era is largely represented by the thousands of coastal traders that moved goods around the country and the tens of thousands of small boats involved in coastal fisheries.

The larger coastal sailing vessels were called bezaisen , the term seamen and shipowners tended to use. The literal origins of the name are vague but probably refer to vessel type— sen as a word ending means “ship”—and sometimes, the word is romanized as benzaisen . More specific terms for the coastal traders include kitamaesen , best translated as “northern coastal trader,” the type that sailed along the Sea of Japan coast to Hokkaidō. From the north, the most common cargo was herring, salmon, and kelp in trade for rice, salt, cotton, cloth, and sake from the mainland. The general public tended to refer to these vessels as sengokubune , literally “one thousand koku ship.” A koku, or about 330 US pounds, is a traditional Japanese unit of measure; one koku was considered to be the amount of rice it took to feed one person for one year.

While the design and construction of traditional Japanese boats and ships, collectively known as wasen (Japanese-style boats), reflect influences from mainland Asia, the Edo period’s isolation did allow boatbuilders and shipwrights to refine tools, designs, and techniques, creating some unique qualities found in Japanese boats.

Throughout the world, one can find a clear progression of boat development, from the dugout canoe of prehistory to semidugout construction (a dugout lower hull with planks added to the sides) to full plank construction. The same can be found in Japan’s interesting variants of small boats. Semidugout fishing boats can still be found today in the Tōhoku region of northern Japan, and in the 1990s, I interviewed perhaps Japan’s last professional builder of dugouts, a boatbuilder in Akita who last built three for fishermen in the 1960s. The Okinawan archipelago features an iconic boat called the sabani, a type of semidugout, and during my first apprenticeship in Japan in 1996, I studied with the last builder of the distinct taraibune, or tub boat, literally a large barrel used for inshore fishing on Sado Island.

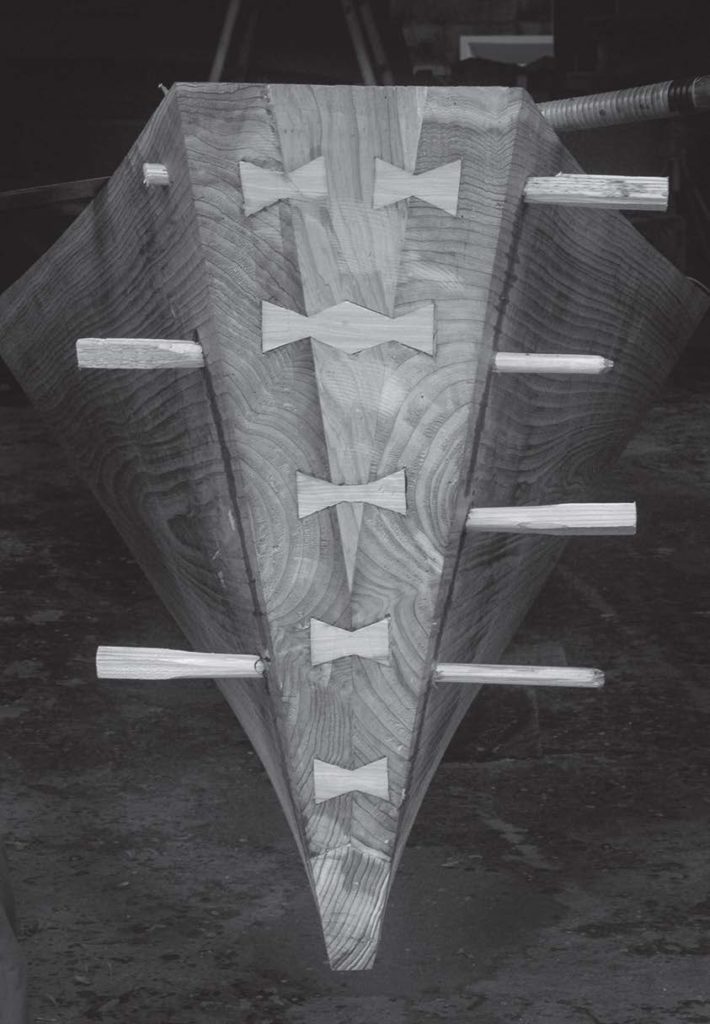

The majority of wasen feature a horizontal plank keel generally twice as thick as the planking with a pair of wide bottom planks rising from the keel at a shallow angle. A pair of top planks run nearly vertical their entire length, meeting the bottom planking at a chine, or hard corner. Where wide planking is built up of several planks, the pieces are edge fastened to each other. In some parts of Japan, sawn frames are installed, but largely the strength of this type of construction rests in the hull itself. In lieu of frames, horizontal beams cross the hull at the chine and the sheer. The beam ends are either tenoned through the hull and wedged from the outside or locked in place with shouldered keys.2 Another feature of Japanese boats is the side planking aft, which often runs past the transom to form a chamber protecting the rudder.

Boatbuilders’ use of edge nails is not unique to Japan, but the technique is definitely highly refined there. Boat nails are made of flat steel, and the holes are cut with a special set of chisels. Today, there is only a single supplier of boat nails in business. This has put a strain on some craftsmen and shows how an important symbiosis exists between craftsmen and attendant crafts that supply their materials.

Another interesting feature of boatbuilding is the process of creating planking with a watertight fit. Using a series of saws, boatbuilders make multiple passes through the seams, a process called suriawase (the term combines the verbs “to rub” and “to assemble”). With each pass, the fit between planks become progressively tighter. Boatbuilders pride themselves on their ability to produce watertight boats without any use of caulking. Only older boats are caulked when they begin to leak.

In my apprenticeships, my teachers stressed the absolute need for me to master the techniques of edge nailing and suriawase. I spent long hours practicing both of these techniques, adhering slavishly to my masters’ instruction. For all five of my teachers, I was their sole apprentice, and each man in his own way communicated his desire to have me carry on his techniques and traditions. One of my teachers was a fourth-generation boatbuilder.

The apprentice system itself represents a major holdover of tradition within the craft of boatbuilding. Learning a craft via apprenticeship with a master is largely forgotten in the West, but in Japan, the notion is well understood and accepted. Unfortunately, Japan’s last generation of boatbuilders today is extremely old. A 2001 survey by the Nippon Foundation in Tokyo found that the average age of Japan’s wooden boatbuilders was sixty-nine. Most never taught apprentices since their careers took place against the backdrop of Japan’s meteoric emergence as one of the world’s largest economies. Furthermore, like practitioners of many crafts, boatbuilders protected their knowledge with an intense secrecy. Many boatbuilders worked entirely from memory, while those that made drawings of their boats left them intentionally incomplete. Even apprentices, unless they were their master’s sons, were kept in the dark, and the phrase nusumi geiko (stolen lessons) is well-known among craftspersons. Apprentices were forced to connive ways to learn crucial dimensions and ratios. One of my teachers told me he slipped back into the workshop at night with a candle and studied his master’s layout of lines.

The traditional apprenticeship was six years with little or no pay. There was no talking in the boat shop and almost no direct instruction. The apprentice was expected to observe the master and learn entirely through observation. A student might spend years just sweeping the shop and caring for the tools, but at the same time, he was expected to watch his master because when the day came for him to actually work on the boat, he was expected to know how to do it. I experienced this pressure with my teachers, and I can say that it certainly focused my attention!

While this type of instruction can seem bizarre or inefficient to the reader, the apprentice’s early months and years in the workshop are hardly wasted in the Japanese context. In order to succeed, the apprentice must learn patience and perseverance and hone his powers of observation. It is a values-based education, something understood to be absolutely necessary before the apprentice can begin to learn the craft. As arduous and inefficient as it may seem, this system produced craftsmen of remarkable skill.

With almost no written record, the craft of boatbuilding today is in real danger of being lost, along with many other traditional skills that have depended on the master-apprentice relationship for sustenance. My research has involved working alongside boatbuilders and recording their designs and techniques. I produce measured drawings of the boats I have built, and I hope to find venues in the future to teach these skills. I have also published the results of my research in magazines and two books. While my efforts to disseminate this information are an obvious break with tradition, the potential loss of a such a unique and refined craft culture strikes me as tragic.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- See Dr. Hiroyuki Adachi’s book Nihon no Fune—Wasen Hen ( Ships of Japan—Indigenous Designs) (Tokyo: Museum of Maritime Science, 1998).

- A tenon is a square or rectangular pin cut into the ends of a beam, which fit into a corresponding mortise, or hole, cut into the face of the planking.

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

Merchant & Makers

The craft of japanese wooden boatbuilding.

Continuing the craft of Japanese boatbuilding - Q&A with boatbuilder, writer & researcher, Douglas Brooks.

A very small sabani a type of semi-dugout once used for fishing in Okinawa. Photo by Mr. Hiroyuki Asato.

Boatbuilder first, then writer & researcher is how Douglas Brooks describes himself in a self-effacing modest kind of way, however, his commitment to the curation and continuation of the ancient but fast-disappearing craft of Japanese boatbuilding is far from moderate, his achievements to date are so much more than mediocre and his ambition to achieve a Japanese boatbuilding institution is massive, fuelled by a monumental passion for this ancient craft.

Douglas Brooks has dedicated himself to documenting never-before-recorded annals of apprenticeships, condensing centuries of ‘stolen lessons’ and hard-earned secrets into a cohesive curation of design, material and technique in order for future generations to be able to appreciate the mastery and aesthetics of a wooden hand-built boat that is a world away from the mediocrity of modern fibreglass vessels.

An ashitenma , a type of small fishing boat from the Inland Sea, built by Douglas Brooks in the Setouchi Arts Festival in 2013. Photo by Simon Wearne.

Here we are privileged to be given an insight into the unique world of Anglo-American-Japanese cultures that Douglas Brooks seamlessly crosses and co-exists within in what has become a life-changing vocation to preserve and perpetuate the skills of traditional wooden boatbuilding in Japan.

Douglas Brooks fits the two side planks of a bekabune under the watchful eyes of his teacher Mr. Nobuji Udagawa. The two built one of these traditional seaweed gathering boats at the Urayasu Museum in 2001. Udagawa built over 300 of these boats during his career. Photograph courtesy KAZI publications, Yokohama, Japan.

Ethnographer, anthropologist, curator, boat-builder… Sometimes apprentice, sometimes master… Please can you outline how you would describe yourself to the reader?

First of all, I would never use the term master for myself. One of the things my experiences in Japan have taught me is the incredible devotion and seriousness craftspeople bring to their work. It’s not “what they do” so much as a calling, or a discipline. In the Japanese context one cannot really call themselves a master until their teacher has passed away. I think the idea of any craftsperson under the age of 60 referring to themselves this way would be considered strange. I consider myself a boatbuilder, writer and researcher. Basically, that is the order in which my career developed. I realised immediately in Japan that my background building boats gave me a unique perspective on the craft that no other researchers possessed. My research explores a very particular niche: documenting the craft and how the objects are made.

Brooks fitting the garboard plank by sawing through the seam while building the shimaihagi , a fishing boat from Aomori Prefecture, that he built in 2003 with his teacher Mr. Seizo Ando. Photo by Catherine Wood Brooks.

Yours is a truly amazing story, can you explain to us a little of your background, in terms of how hailing from the US Eastern seaboard, with its obvious maritime traditions, along with a chance friendship with a Japanese room-mate, has led to a life-changing fascination with Japanese boatbuilding?

I was raised in Deep River, Connecticut and my father always had a small fishing boat so I was on the water from an early age. I drifted away from fishing but loved boats, and eventually got into sailing and bought myself a small sailboat while in high school. While at Trinity College I attended the Williams College Mystic Seaport Program in American Maritime Studies (now just called Williams Mystic). Mystic Seaport is North America’s largest maritime museum and while there I got to do an internship with the museum’s boatbuilder. I helped him build a small skiff and do some other repair work. It was just a taste of boatbuilding but it definitely intrigued me. The next year I attended the University of Oregon where my roommate Nobu Hayashi was from Japan. We became close friends and in the years after college he kept inviting me to visit his native country. I eventually found work in the Small Boat Shop of the maritime museum in San Francisco and spent five years there getting more immersed in building and curating traditional boats. When I left that job in 1990 Nobu immediately sent me a plane ticket to Japan with a note that said, simply, “Now you have no excuses.” On that first trip, I met several boatbuilders, including the man who would become my first teacher six years later. I began to get an inkling of the crisis in the craft: all the boatbuilders were elderly and none had taught apprentices. Very little was written down and the craft depended entirely on the apprentice system for its survival. I saw immediately how the work of these amazing craftsmen deserved to be preserved somehow, and eventually that led to studying directly with boatbuilders in order to document their design secrets and techniques.

Brooks’ teacher in Tokyo, Mr. Kazuyoshi Fujiwara, runs a saw through a seam to fit two planks together. Brooks studied with Fujiwara in 2002.

What distinguishes Japanese wooden boatbuilding from your other areas of expertise; Anglo & American boatbuilding, in terms of tools, craft technique, materials used, etc?

In a broad sense, Western boats are based on a framework that is then planked, a skeleton-like arrangement. Japanese boats tend to have very little framing, relying instead on much thicker planks which are edge-fastened to each other, something called shell-type construction. Japanese boats are also almost always hard chine, meaning the strakes of the hull meet at angles, or knuckles. There are really no round-hulled, smooth planked traditional boats in Japan, except for dugouts. The greatest similarities between Western and Japanese boats can be found in the dugout and semi-dugout varieties. In most Western boats seams are made watertight with cotton caulking, but in Japan a very sophisticated technique is used to made plank seams watertight without caulking. A series of ever finer saws is run though the seams in a very particular way, and with each pass the seam fits tighter and tighter. The technique is called suriawase, and a good translation is “to reconcile.” It takes quite a bit of practice to master. Japanese do caulk boats, using the inner bark of the cypress tree, but this is reserved for older boats whose seams have opened up, and the caulking is driven from the inside.

A scow schooner yawl boat, built by Douglas Brooks while working at the National Maritime Museum in San Francisco.

Western apprentices in traditional crafts in Japan are extremely rare; can you outline to us what are the main distinctions, would you say, between a Western & Japanese apprenticeship, beyond the obvious linguistic differences?

Interesting you end your question with the mention of linguistics, because I think the salient difference between Western and Japanese notion of apprenticeship is that there is no teaching in the latter. All six of my teachers told me on my first day there would be absolutely no speaking in the workshop. Questions were sometimes tolerated though my teachers’ irritation at being interrupted was palpable. If I did ask a question the answer was generally either mite wakaru or matte wakaru: “Watch and you will understand” or “Wait and you will understand.” Ironically, the lack of speaking meant that language was not an obstacle in my apprenticeships. Though my Japanese has improved steadily over the years, I barely spoke the language at all at the time of my first apprenticeship, but this didn’t matter, because my teacher did not speak to me! The upshot of this kind of training is the apprentice is expected to learn by observation only. This puts incredible pressure on the apprentice, needless to say, but these pressures are also considered an essential part of the training. What becomes clear is the apprentice is fully responsible for his or her learning. While my teachers accepted the premise of my work, they felt no responsibility whatsoever for making sure I understood everything; that was my problem. It is very much a values-based style of learning, first inculcating humility (all my teachers told me my previous boatbuilding experience meant nothing), and then forcing the apprentice to develop a laser-like focus on the work. All of my teachers pointed to the broom my first day, and all I did at the outset was sweep, fetch tools, and move material. After a certain interval, I would be asked to work on the boat, but the understanding was that if I didn’t perform the work perfectly I was going back to sweeping. It’s a style of learning that provides a lot of motivation.

Mr. Hiroshi Murakami adzing the back of the stem of an isobune , or inshore fishing boat, during the author’s apprenticeship with him in 2015. Murakami is the last active boatbuilder in the region devastated by the 2011 tsunami. The isobune is the most common type of small fishing boat in the region, hundreds of which were destroyed in the disaster. Brooks is currently working on a book documenting the design and construction of these boats.

It is well known that it is a great honour and achievement to be accepted as an apprentice to a Japanese master, can you shed any light on how you have managed to become an apprentice to not one but six different masters over the years, with a seventh apprenticeship planned shortly?

For the most part it was because I developed relationships with my teachers. I met my first teacher in 1990, then I saw him again, interviewing him with the help of an interpreter in 1992 and 1994. At the end of the third visit his invited me to become his apprentice. He told some mutual friends that I showed perseverance and commitment and this convinced him to take me on. The process was much the same with my second teacher. Some of my other apprenticeships were arranged by intermediaries. I think all of my teachers supported the idea of my research. They certainly understood the precarious state of their craft better than anyone. I was the only person to come along expressing an interest in their work, and to varying degrees each of my teachers saw me as the only chance they had to pass along that knowledge. In addition, I have travelled to forty-five of Japan’s forty-seven prefectures meeting and interviewing almost sixty boatbuilders.

The launch of the chokkibune , an Edo-era water taxi built by Douglas Brooks and his teacher, Kazuyoshi Fujiwara, in Tokyo in 2003.

Part of your aim is to document what is historically an oral tradition in order to preserve and retain traditional Japanese boatbuilding design & techniques. How does this work when a major part of Japanese craftsmanship is the culture of secrecy and almost the ‘stealth’ of knowledge and expertise from the master by the apprentice?

There is a well-known phrase in Japanese crafts called nusumi geiko, or “stolen lessons.” If the apprentice was not a family member often the master would withhold critical information from them. It was up to the apprentice through guile to steal those secrets. My first teacher told me he used to sneak into his master’s workshop at night with a candle and study his layout. He eventually figured out the critical dimensions of the boat, and also discovered his master had been snapping meaningless lines in an attempt to fool him! Also, where boat drawings do exist almost all are incomplete; you cannot build a boat from them. The missing information was memorised by the builder.

A copy of a plank drawing. While the profile view is complete, the plan view is missing lines showing the chine and sheer, rendering the drawing useless. The missing information would be memorised by the builder.

One of my teachers would make patterns when building a boat but he burned them at the end of the project. In some ways, I came along at just the right time. My teachers were in their seventies and eighties when I met then and most had been put out of business by fibreglass boats. They had come to a point where they understood the craft was about to disappear and there was really no longer an incentive to keep secrets. That said, some of my teachers still remained close-lipped, not revealing certain secrets to me, and I had to figure these things out for myself. At one boat launching my teacher said, “Mr. Brooks understood 95% of what I did, but I am not going to tell him what the 5% was he did not understand.” While this attitude may rankle Westerners, it is really something embedded in Japanese crafts.

A shimaihagi fishing boat built by Brooks and his teacher Mr. Seizo Ando in 2003. This type of boat was used on the far northern coastline of the main island of Japan in Aomori Prefecture. Most of the regions’s wooden boats feature elaborate carvings decorating their hulls.

How did your Masters feel about you recording their ‘secrets’?

In all but one case I really had no problems. As mentioned before most of my teachers understood fundamentally what I was trying to accomplish. What varied was how hard or easy they were going to make it for me. One teacher exploded when I tried to trace one of his patterns. He said I was stealing his secrets. When I said my goal had been clear at the outset of the project that I was going to be recording his work for publication he said he understood. It turned out he was absolutely opposed to his secrets being revealed locally, even though he was the last boatbuilder of the region and all the wooden fishing boats were rotting away in boathouses. Oddly, after this altercation he restated that I was not to trace his pattern. Then he ordered me to clean the shop and close up. He walked out and of course I promptly traced the pattern. I don’t know how he could have thought I wouldn’t, but maybe this was a kind of kabuki, where he felt compelled to state his position regardless of what I might do.

A bekabune , or seaweed gathering boat, built by Douglas Brooks and Mr. Nobuji Udagawa in 2001. Japanese boatbuilders don’t use clamps, preferring to hold parts in place and bending planking using props. The line of mortises visible in a sheer (upper) plank are for the edge-nails that join the upper and lower plank together.

Your dedication & passion for Japanese wooden boatbuilding has not gone unnoticed; you are a highly-respected author, teacher, lecturer & project leader, with achievements such as the Anderson Garden project and honours such as the Rare Craft Fellowship Award from the American Craft Council to your name… What would you say is your proudest achievement/most important moment so far and upon retirement, and what sort of legacy in the craft-world would you like to leave behind?

I find writing and teaching very rewarding. At this point, Japan’s boatbuilders are rapidly disappearing, and the opportunity to work with the last generation of traditional boatbuilders simply won’t exist in five years, ten at the most. I want to transition my own work to finding ways to disseminate what I have learned, through how-to books, workshops, lectures, etc. I’ve done three boatbuilding projects in Japan where I brought in apprentices, and in 2015 and 2016 I taught a course in Japanese boatbuilding at Middlebury College in Middlebury, Vermont.

Middlebury College students in the boat they built in a 2015 Winter Term class taught by Brooks. The boat is a type of river fishing boat from the Hozugawa River near Kyoto. Fifteen students built this boat and another river boat in one month. Photograph by Trent Campbell.

The key is to give a new generation of craftsmen the means to build these amazing boats. Sadly, the apprentice system is not the answer. It simply takes too long, though I have been thinking very seriously about a boatbuilding school, the model of how the revival of Western boatbuilding has been energised and sustained. Ultimately, if I can make a contribution to preserving these remarkable skills I will have done a small part in repaying my teachers’ amazing generosity.

Japanese Wooden Boatbuilding , Douglas Brooks’ fourth book. This book chronicles the first five of Brooks’ apprenticeships, and is the first comprehensive survey of the craft. Signed and inscribed copies are available from the author at www.douglasbrooksboatbuilding.com .

For anyone considering becoming an apprentice in a traditional Japanese craft, are you able to provide any advice?

First, to clarify, I worked with my teachers over the course of building one boat (two in the case of my Tokyo teacher). That time frame varied from two weeks to seven months. The average boatbuilding apprenticeship in Japan lasted six years, but one must remember the apprentice came in at age 14 or 15 with no skills whatsoever. It’s not an efficient system; apprentices might spend two to three years before they ever did any significant work other than cleaning and sharpening. Some boatbuilders have told me they spent the first year of their apprenticeships helping their master’s wife in the kitchen. Despite what my teachers said about my previous experience being of no use to me, they were wrong. I knew how to sharpen and use the tools, and as time went on I understood the design and techniques of Japanese boatbuilding. I am contacted fairly regularly by people who find my website and express an interest in apprenticing in Japan. What I tell them is they need to go to Japan, find a potential teacher and then demonstrate their willingness to do what it takes to learn the craft. Other Westerners I’ve met who have studied Japanese crafts tell stories not dissimilar from my own. The culture of Japanese crafts demands a total commitment, and people have to prove they are serious.

A yuta , or shaman, presides over the launching of an eight metre sabani built by Brooks and his teacher Mr. Ryujin Shimojo, visible at right. Photo by Sgt. Emery Ruffin, USMC.

That said in some ways there couldn’t be a better time to study the crafts, because so many masters are elderly and want apprentices. It’s very bittersweet for me, because the apprentice system, while brutal in some regards, nevertheless turned out craftspeople of incomparable skills. The problem is in today’s world you are not likely to find many people willing to work years for little or no pay.

The chokkibune being sculled in a canal in Tokyo. The Japanese ro , or sculling oar, is similar to the Chinese yuloh .

You have written extensively on the subject of traditional Japanese boatbuilding. Who are the books aimed at, and what could a reader expect to glean from them?

My first three books are strict how-to manuals on particular boats. The first book, on how to build the tub boat of Sado Island, became a textbook used in a series of tub boat making workshops on Sado. Eventually several dozen people made tub boats and now one of them is making them professionally again. My fourth book, Japanese Wooden Boatbuilding, is the story of my first five apprenticeships and is the most comprehensive survey published of the craft. I hope it gives a generous overview to the reader. I am right now working again on another how-to book – the 21-foot fishing boat from the tsunami zone – and my goal is to give a competent woodworker enough information to build this boat for themselves. This is where I would like to keep going with my writing. One dream would be to publish a book entitled Ten Japanese Boats You Can Build. With the collapse of the traditional apprentice system and the disappearance of craftspeople we have to find a way to give people the ability to build these boats.

A woman spearing shellfish from a taraibune , or tub boat, on Sado Island. These boats are still used in six fishing villages on Sado Island in the Sea of Japan. Primarily used by women, they traditionally provided a cheap, durable second boat for fishing families. As a result they were mainly used by women. Brooks apprenticed with the last builder of these boats in his first apprenticeship in 1996, and his first book documented how these boats are built.

Given the rise of modern fibreglass boat in recent decades, why do you think traditional wooden boats are still relevant in the modern world?

It’s a craft, one with a fascinating history. Like any craft, people derive enormous pleasure and satisfaction from the work. There is something inherently enriching about pursuing mastery, and seeing the tangible results of one’s work is extraordinarily fulfilling. Traditional boats reflect rich and varied histories and aesthetics, and their use encompasses a different kind of journey, no less enriching.

Douglas Brooks and Seichi Nasu pose in front of a rice field boat Nasu built.

What is the main difference between sailing a traditional Japanese vessel compared to the more familiar Western wooden sailing boats?

The only sailing vessel I built in Japan was the sabani of Okinawa. The sabani is an extraordinarily difficult boat to sail, and I have almost no experience at it. Otherwise all the boats I’ve studied were powered by paddle or sculling oar. The latter comes from China and is a large and powerful way to move a boat versus Western oars.

An Okinawan sabani sailing . These boats have enjoyed a revival in Okinawa, and race throughout the year. Photograph by Hiroyuki Asato.

Where do you see your journey within the craft of traditional Japanese boatbuilding going next?

I was just in Japan building a boat for a famous garden in Takamatsu City. While there I met with an 85-year old boatbuilder, perhaps the last builder of the iconic cormorant fishing boat. I will be returning in May to study with him and document his work. I see more opportunities to build boats in Japan and I hope to continue teaching and writing. As mentioned before, if I could find the support of an institution I really think Japan is ripe for a boatbuilding school.

An ukaibune , or cormorant fishing boat. These unique boats are very rare and Mr. Seichi Nasu, age 85, is perhaps the last man who knows how to build them. Douglas Brooks will be apprenticing with Nasu and documenting his design and techniques beginning in May of 2017.

Thanks to Douglas Brooks for taking time out of his busy schedule to answer our questions. All photographs by Douglas Brooks unless otherwise noted. Be sure to follow Brooks’ upcoming work in Japan at his blog: http://blog.douglasbrooksboatbuilding.com/ .

www.douglasbrooksboatbuilding.com

- By Gerry Jones

- March 16, 2017

- SHOW COMMENTS (7)

Enjoying Merchant & Makers?

Subscribe to our occasional newsletters for the latest articles and updates

Great news, we've signed you up. Sorry, we weren't able to sign you up. Please check your details, and try again.

POST A COMMENT

You must be logged in to post a comment.

7 Responses

[…] viagra pricing today […]

[…] natural male viagra […]

[…] generic cialis canada […]

[…] viagra 25 […]

[…] 200 mg dosage of cialis […]

[…] 50 mg sildenafil price […]

[…] online casinos that accept ukash […]

Sign up to our newsletter to be the first to hear about new posts and articles.

Skip and close

bottom_desktop desktop:[300x250]

- Competitions

- Print Subscription

- Digital Subscription

- Single Issues

Your special offer

Subscribe to Sailing Today with Yachts & Yachting today!

Save 32% on the shop price when to subscribe for a year at just £39.95

Subscribe to Sailing Today with Yachts & Yachting!

Save 32% on the shop price when you subscribe for a year at just £39.95

Sailing in Japan

Japan remains an obscure sailing ground, despite being a highly developed country. nick and jenny coghlan enjoyed a surreal cruise.

Preparing for Sailing in Japan

E verybody had warned us that the Japanese love paperwork. So as Bosun Bird, our Vancouver 27, worked her way northwards through the islands of the western Pacific, every so often we’d crank up the Iridium satphone to find out what we needed to do before entering the country. By the time we reached Guam, the American territory and military base that was to be our jumping-off point for the 1,400-mile crossing to Kyushu, we were getting desperate. We finally got hold of a seemingly helpful young lady:

“You are very welcome. Please send now fax with exact arrival time and place. Thank you.”

“OK. Can we send an email instead?”

(Repeat this exchange several times, until the lady quietly hangs up.)

Finding a fax these days is challenging; the Guam Mission to Seamen finally located a dust-covered machine in their junk cupboard. It was with nostalgia and amazement that we plugged it in, and there was that long-forgotten whirring and beeping. With a mental shrug – who can estimate an arrival time after a crossing of 1,400 miles? – we sent a message and put to sea.

Next day, on the horizon to starboard we had the low flat outline of Tinian: from here the Enola Gay, an American B-29, took off before dawn on August 6 1945, to drop the first atomic bomb. Idly, I wondered if it was going to be possible to talk to Japanese about the war.

It soon turned into a rough passage. But most worrying was the shipping. We’d installed an AIS receiver in New Zealand, anticipating heavy traffic in these waters. It was difficult as we closed on Kyushu not to feel panic as the tiny screen of our chart-plotter showed up to 40 targets at a time. But at last, after a nervous night dodging small fishing boats with unfamiliar light arrays (and none of them with VHF) we motored into the calm waters of the great bay of Kagoshima-wan.

Sailing in Japan: Unknown territory

An unfamiliar scent of spruce wafted towards us. A high-speed hydrofoil buzzed past at 35 knots; a propeller plane with that famous red-sun symbol flew low to take a look at us. And at the head of the bay, Sakajima volcano was having one of its frequent bouts of activity.

We zigzagged in to the port through a maze of concrete breakwaters. Out of the corner of my eye I saw fifteen or so men, mostly in uniform, standing sharply to attention on one pier. One of them saluted. We paid no further attention, occupying ourselves instead with a newly learned tie-up routine (nose-in, at right angles to the wall, secured on each quarter to buoys). Old friends Mel and Phil, on Mira, had beaten us by two or three days and welcomed us, babbling with their news; Mel had an ugly waffle-shaped scar on her thigh, from when they’d taken a knockdown and she’d fallen on the stove.

By sheer chance, and for perhaps the first and last time ever, Bosun Bird had arrived exactly when we said we would. Yes, we now realised, those men in the Toyota blazers, peaked caps and white gloves were our reception committee. Two-by-two they clambered down, each pair presenting us with the same long and baffling ‘General Declaration.’ The final couple politely gestured that we should land, and ushered us into their car. We had no idea what was going on. More arcane paperwork at their office, smiles, then they drove us back. In the cockpit we found a case of Kirin beer, a large watermelon and two packages of sushi. Phil shrugged with a smile:

“That’s Japan for you. Just strangers making you welcome.”

Sailing in Japan has its challenges. For one, the bureaucracy never gives up. For every single destination other than four or five designated Open ports, you must have specific entry permission. Early on, we learned that it is wise to request permits for every conceivable stop. But the officials are charming.

As we waited patiently in Hiroshima one morning for our next list of authorised ports to be typed up, the woman in charge of the office pulled some coloured squares of paper from under the counter. She patiently instructed us on how to fold them so as to make origami cranes.

Sailing inshore waters in summer is generally tranquil, the winds light and variable: you may need to use your engine a lot. We did need to keep an eye open for warnings of typhoons (the North Pacific equivalent of hurricanes/cyclones), but the two to three days’ notice that we always had, coupled with the large number of typhoon-proof artificial harbours, meant that this was not a major concern.