Sailor Cole Brauer makes history as the first American woman to race solo around the world

Aboard her 40-foot racing boat First Light , 29-year-old Cole Brauer just became the first American woman to race nonstop around the world by herself.

The New York native pulled into A Coruña, Spain, on Thursday after a treacherous 30,000-mile journey that took 130 days.

She thanked a cheering crowd of family and fans who had been waiting for her on shore.

“This is really cool and so overwhelming in every sense of the word,” she exclaimed, before drinking Champagne from her trophy.

The 5-foot-2 powerhouse placed second out of 16 avid sailors who competed in the Global Solo Challenge, a circumnavigation race that started in A Coruña with participants from 10 countries. The first-of-its-kind event allowed a wide range of boats to set off in successive departures based on performance characteristics. Brauer started on Oct. 29, sailing down the west coast of Africa, over to Australia, and around the tip of South America before returning to Spain.

Brauer is the only woman and the youngest competitor in the event — something she hopes young girls in and out of the sport can draw inspiration from.

“It would be amazing if there was just one girl that saw me and said, ‘Oh, I can do that too,’” Brauer said of her history-making sail.

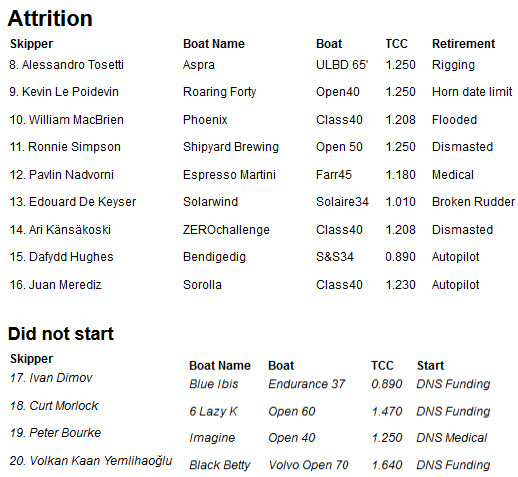

It’s a grueling race, and more than half of the competitors have dropped out so far. One struck something that caused his boat to flood, and another sailor had to abandon his ship after a mast broke as a severe storm was moving in.

The four-month journey is fraught with danger, including navigating the three “Great Capes” of Africa, Australia and South America. Rounding South America’s Cape Horn, where the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans meet, is often likened to climbing Mount Everest because of its perfect storm of hazards — a sharp rise in the ocean floor and whipping westerly winds push up massive waves. Combined with the frigid waters and stray icebergs, the area is known as a graveyard for ships, according to NASA. Brauer said she was “so unbelievably stoked” when she sailed past Cape Horn in January.

Marco Nannini, organizer of the Global Solo Challenge, said the comparison to scaling Mount Everest doesn’t capture the difficulty of the race. Sailing solo means not just being a skipper but a project manager — steering the boat, fixing equipment, understanding the weather and maintaining one’s physical health.

Nannini cited the relatively minuscule number of people who have sailed around the world solo — 186, according to the International Association of Cape Horners — as evidence of the challenges that competitors face. More than 6,000 people have climbed Mount Everest, according to High Adventure Expeditions .

Brauer stared down 30-foot waves that had enough force to throw her across the boat. In a scare caught on camera, she badly injured her rib near the halfway point of the event. At another point, her team in the U.S. directed Brauer to insert an IV into her own arm due to dehydration from vomiting and diarrhea.

She was able to stay in constant communication with members of her team, most of whom are based in New England, and keep herself entertained with Netflix and video calls with family through Starlink satellites. That’s also how Brauer was able to use Zoom to connect with NBC News for an interview, while she was sailing about 1,000 miles west of the Canary Islands.

While Brauer was technically alone on First Light, she had the company of 450,000 followers on Instagram, where she frequently got candid about life on an unforgiving sea while reflecting on her journey.

“It all makes it worth it when you come out here, you sit on the bow, and you see how beautiful it is,” she said in an Instagram video, before panning the camera to reveal the radiant sunrise.

Brauer grew up on Long Island but didn’t learn to sail until she went to college in Hawaii. She traded in her goal of becoming a doctor for life on the water. But she quickly learned making a career as a sailor is extremely difficult, with professional racers often hesitant to welcome a 100-pound young woman on their team.

Even when she was trying to find sponsors for the Global Solo Challenge, she said a lot of people “wouldn’t touch her with a 10-foot pole” because they saw her as a “liability.”

Brauer’s message to the skeptics and naysayers? “Watch me.”

“I push so much harder when someone’s like, ‘No, you can’t do that,’ or ‘You’re too small,’” Brauer explained.

“The biggest asset is your mental strength, not the physical one,” Nannini said. “Cole is showing everyone that.”

Brauer hopes to continue competing professionally and is already eyeing another around-the-world competition, but not before she gets her hands on a croissant and cappuccino.

“My mouth is watering just thinking about that.”

Emilie Ikeda is an NBC News correspondent.

Solo Challenge

American Cole Brauer Takes on Global Solo Challenge as Youngest and Only Female Competitor

- Global Solo Challenge

©Cole Brauer

We are delighted to announce a notable addition to the upcoming Global Solo Challenge roster. Pushing the boundaries of this event Cole Brauer from Boothbay, Maine, USA, steps into the limelight as the first and currently the only female competitor. She will also be the youngest entry in the event at just 29 years old.

Brauer will undertake this challenge on her Class40 yacht, christened ‘First Light’. Cole’s fascination with sailing traces back to her childhood spent exploring the natural wonders of a nature preserve. Her move to Hawaii for university opened the gateway to the sailing community, which embraced her and fueled her passion for the water.

Her passion for single-handed sailing was ignited through an enlightening conversation with mentor Tim Fetsch, and further fueled by the inspiring life story of famed sailor Ellen McArthur . With a growing affinity for single-handed sailing and an insatiable ambition to become the First American Woman to Race Solo Around the World, the Global Solo Challenge seemed a fitting event to register for.

Brauer’s preparation for the race hinges on her meticulous planning, robust team support, and an understanding of her yacht, ‘First Light’, like no other. She recognizes the substantial hurdles she will face, particularly considering her late entry, but Brauer is no stranger to overcoming challenges.

Furthermore, Brauer’s participation is underpinned by a powerful social message. She aims to disrupt the prevailing ‘traditional’ mindset in sailing, a sport known for its male dominance. Advocating for a more inclusive and respectful environment, she aspires to inspire change, fostering a community that encourages and respects women sailors.

Cole Brauer’s entry into the Global Solo Challenge sets a new course for the event. We eagerly anticipate her performance, as she embodies the spirit of determination, resilience, and aspiration in this demanding event.

Where does your passion for sailing come from?

When I was a kid there weren’t many opportunities to sail, and when there were, they were either very expensive (yacht club prices) or the boats didn’t interest me because they were slow, bulky and the classes were rigid.

I grew up on a nature preserve, wandering through the tall grass of the creek and playing in the mud watching the tide come in. I spent a lot of time alone exploring nature. I was fascinated with clouds, animal bones, and watching the weather roll by. Pretending I was a fairy flying through the creek observing every movement, every puff that pushed the reeds one way or the other. When I moved to Hawaii for University, all I wanted was to get out on the water. Feel at home. Accessing the sailing community in Hawaii was the logical step. I had no idea that this entire community was going to take me under their wing the way they did and push me to pursue my wildest dreams.

What are the lessons you learned from sailing?

Sailing has taught me that I am never truly alone. I was in Hawaii away from my family on an island for so many years yet I was never homesick. The sailing community taught me everything there was to know about sailing and racing while also giving me life lessons throughout the way. For instance: to never forget that life is so incredibly short. You can work in an office for 40 years and come out and your body deteriorates and you can’t do the things you used to do. Yet if you take this time while you are young to make the most of it. Money will come. You may never have enough money to be “rich” but you will have enough to be content and secure. It’s all a mindset. This was taught to me by the sailing community.

What brought you to like single-handed sailing?

I was sitting having dinner with a mentor of mine, Tim Fetsch, in 2018 and we were talking about goals and what I wanted to accomplish in my sailing career. I was 24 years old at the time. And Tim asked me what do you want to do? I said the Volvo Ocean Race. He said “you really want to sail around the world?” I had just returned from a watch captain gig on a 7 person team in the Pacific Cup, a race from San Francisco to Hawaii. I said “of course!” He said “have you ever heard of Ellen McArther.” I said no (I hadn’t grown up sailing so I was lacking idols). He then sent me her book, ‘Taking on the World’. I read it in two days on a boat delivery. That was it. I was going to race solo around the world. I was going to do it as a 5’2’’ 100lb woman. Just like Ellen McArther. And the best part! I actually loved single-handed sailing more than fully crewed by a long shot! I had found my footing.

What prompted you to sign up for this event?

My co-skipper, Cat Chimney, recommended this race to me because it falls in line with the overall goal of being the First American Woman to Race Solo Around the World. While giving the team and I four years to prepare for the 2028 Vendee with a World Race under our belt.

How do you plan to prepare for this event?

I have a strong team behind me. I have been prepping some of these members of this team for years now. They have all known my goals and aspirations. I have written a timeline, schedule, estimated cost and communicated my expectations while also keeping the conversation honest and open with each one of my teammates. Without these teammates, I would not be able to do this race.

What do you think will be the biggest challenge? The biggest challenge will be making the starting line, since I and the team are coming into this event late to the game.

Tell us about your boat.

‘First Light’ is a Class40, she was formerly owned by Michael Hennessy and formally named Dragon. She has a strong pedigree and has been loved since her inception. I know the boat better than any other boat I have ever sailed. We have a strong understanding of each other.

Do you intend to link this personal challenge with a social message?

This goal has always been to be the First American Woman to Race Around the World. With this goal, I hope to show that this very male-dominated sport and community CAN become more open and less “traditional.” This is changing a mindset that has been set in stone by many boat clubs, yacht clubs, and people (women and men). I will be fighting against the constant sexual, verbal, and physical harassment for not just myself but for the Corinthian and Professional women sailors in this sport. As professional sailors, we have been fighting for many years for equal pay (we are paid significantly less than a man in the same position), we are harassed by teammates, owners, clients, race organizers, and many others in this community. Just as well as this community has built me up it has broken me and my fellow female teammates down. I am doing this race for them. Please follow safesail.org , this is an organization that is changing the world of sailing as we know it. It is giving people an opportunity to report harassment to listening ears in the sailing community.

Sailing achievements or racing palmares.

I hope that this race will be my biggest sailing achievement to date.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

I would like to thank my team. Thank you for supporting me before and during this upcoming event! I can’t do this without them; I understand this very clearly. Thank you to the Day family, I love this boat so much and I’m so unbelievably happy I have the opportunity to sail her. I have said for a long time that if I am going to sail around the world I am going to do it on a boat I know, love, and trust. This is the one. Thank you to my immediate support team, FK and Linc Day, Philip Carlsson, Cat Chimney, Serena Village, Zach Mason, Jimmy Carolla, Kyle Wishart, Chelsea Freas, and James Tomlinson. I’m sure we will grab a lot more people as this process carries on but I will never forget the beginning squad and how much support you have already provided!!

Latest Updates

News articles.

Global Solo Challenge Copyright © 2022. All rights reserved. Website created by Primeconsulting

The Event, its name, logo, website, social media pages and all their content are the sole property of Marco Nannini LTD, 3rd floor, 166 College Road, Harrow, Middlesex, HA1 1BH, UK. All rights, title, intellectual property, Copyright, contractual and other entitlements of and relating to the Event, its name, logo, website, social media pages and all their content, vest in and are retained by Marco Nannini LTD.

Home News Congratulations to Cole Brauer for finishing the Global Solo Challenge!

Congratulations to Cole Brauer for finishing the Global Solo Challenge!

She finished in second place, setting a new Class40 around-the-world speed record and amassing 450,000 followers on Instagram in the process. At just 29 years old, Brauer was both the youngest skipper and the only female sailor in the fleet of 16 boats. On behalf of US Sailing, we want to congratulate Cole on her amazing achievement! Thank you for representing the US on the world stage and for inspiring the next generation of sailors. US Sailing Board president had this to say to Cole:

On behalf of the Board of Directors of US Sailing, American sailors, and adventurers, congratulations on such an incredible and groundbreaking accomplishment!

Your journey has been gripping and inspiring for us all.

Just finishing is amazing in itself, so to finish second in such a distinguished body of competitors is an unparalleled achievement.

Along the way, you have brought the magic of sailing to a wide audience by showing the world your journey on social media. You have represented American sailing in a most spectacular way – well done!

With respect and appreciation,

Richard Jepsen, Board President

Copyright ©2018-2024 United States Sailing Association. All rights reserved. US Sailing is a 501(c)3 organization. Website designed & developed by Design Principles, Inc. -->

Recommended

Ny skipper cole brauer overcame broken ribs, deteriorating boat to become first us woman to sail solo around the world.

- View Author Archive

- Email the Author

- Follow on Twitter

- Get author RSS feed

Contact The Author

Thanks for contacting us. We've received your submission.

Thanks for contacting us. We've received your submission.

She sailed her way into the history books.

A 29-year-old skipper from New York has become the first US woman to sail solo around the world.

Cole Brauer, from Long Island, tearfully reunited with her family in A Coruña, Spain, on Thursday after a gruelling 30,000-mile journey that took 130 days.

The 5-foot-2 trailblazer placed second out of 16 in the daring Global Solo Challenge, which kicked off in October off the coast of the port city, located in northwestern Spain.

“I can’t believe it guys. I sailed around the world,” Brauer said as she approached the finish line in an Instagram live video. “That’s crazy. That’s absolutely crazy. This is awesome. Let’s just do it again. Let’s keep going!”

She was the only woman in the event and also the youngest competitor. She sailed into A Coruña to a cheering crowd just a day before International Women’s Day on March 8.

“It would be amazing if there was just one girl that saw me and said, ‘Oh, I can do that too,’” Brauer told NBC of her history-making effort. More than half of the other competitors has dropped out as of Thursday.

Brauer’s sailing profile on Global Solo Challenge’s website said her goal has always been to be “the First American Woman to Race Around the World.”

“With this goal, I hope to show that this very male-dominated sport and community can become more open and less ‘traditional,'” it reads.

The East Hampton native didn’t even take up sailing until she decamped to the University of Hawai’i for college in 2014, her profile explained.

“I grew up on a nature preserve, wandering through the tall grass of the creek and playing in the mud watching the tide come in,” she said of her childhood in Suffolk County.

“When I moved to Hawaii for university, all I wanted was to get out on the water. Feel at home. Accessing the sailing community in Hawaii was the logical step,” she added.

Brauer turned pro after college, and started seriously chasing the idea of a round-the-world race after her mentor, Tim Fetsch, sent her a book by record-setting female skipper Dame Ellen MacArthur.

By the time she set sail on her global adventure on Oct. 29, Brauer was already a record-setter: Last summer, she became the first woman to win the Bermuda One-Two race, the Providence Journal reported at the time.

Brauer documented the treacherous Global Solo Challenge for her 459,000 Instagram followers from aboard her beloved 40-foot monohull racing boat, First Light.

Like her pint-sized, 100-pound owner, First Light has a quicksilver edge – and is only large enough to typically hold a one- or two-person crew.

The race path took Brauer down the western coast of Africa before she sailed into the Southern Ocean in early December, where she’d cement second place in the challenge.

She often showed fans her peaceful mornings and on-board workout sessions in the Atlantic Ocean.

“Cole wants to prove you can go around the world and watch Netflix every once in a while, and wear your pajamas,” her media manager, Lydia Mullan, told the New York Times of the realistic look at boat life.

“As for her mental health, she’s really creating a space in her routine for herself, to create that joy she hasn’t seen in other sailors,” Mullan added.

But even Brauer’s tenacious outlook at times gave way for the hardships of living at sea.

In December, she suffered a rib injury when she was violently thrown across her boat because of broaching — when a boat unintentionally changes direction toward the wind — in the rough waters near Africa.

Despite the injury, Brauer said she had no other choice but to power through the pain and keep sailing.

“There’s no option at that point. You’re so far away from land that there’s no one who can rescue you or come and grab you,” she told the “Today” show Thursday. “You kind of just need to keep moving along and keep doing everything.”

Brauer’s grit during the journey recalled her time in Hawaii, when she borrowed from her background as a varsity soccer player, track and field runner, and cheerleader to thrive on the UH team — all while juggling her studies in nutrition science and a full-time job.

“It’s more strategy than anything,” she told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser in May 2016, when she captained the four-time national championship-qualifying team.

Brauer told NBC on Sunday that solo sailors “have to be able to do everything.”

“You have to be able to get up even when you’re so exhausted and you have to be able to fix everything on the boat.”

She reached the Pacific Ocean on December 29 and traveled past the southernmost point of South America and back into the Atlantic on January 27.

As she missed the holidays back home, Brauer decorated First Light with decorations fit for the occasion — pumpkins and ghosts for Halloween, a small felt Christmas tree, and broke out a dress and champagne for New Year’s Day.

Brauer also told the outlet that she started to feel the boat “deteriorating” and “starting to break down” as she made her final push through the Atlantic.

She then deliberately slowed her arrival time near the finish line to coordinate with the “first light” — when light is first seen in the morning — in honor of her boat’s namesake.

“I’m glad that out of all times, I’m coming in at first light,” Brauer said. “It’s only necessary.”

As she crossed the finish line, Brauer held two flares above her head to signal an end to her over four-month-long campaign.

“Amazing finish!!!! So stoked! Thank you to everyone that came together and made this process possible,” she wrote on Instagram.

Following her second-place finish, Brauer received a fresh cappuccino and croissant, the breakfast she had been craving for months while at sea, she said.

French skipper Philippe Delamare, who started the race a month before Brauer, won the Global Solo Challenge on Feb. 24. Start dates were staggered based on performance characteristics.

A highlight of Brauer’s return to dry land will be reuniting with her mom, dad, and younger sister.

“They think I’m nuts,” Brauer told the Providence Journal of her parents’ response to her big sailing dream.

“I think that they’re much more proud of me now, especially because they’re starting to realize that this 10-year adventure I’ve been on isn’t just me gallivanting around the world…not really fulfilling what my mind and body was made to do, which is what my parents always wanted me to do,” she added.

Now, Brauer is joining a storied lineage of esteemed female skippers who came before her.

Polish skipper Krystyna Chojnowska-Liskiewicz was the first woman to sail solo around the world, traveling almost 36,000 miles from 1976 to 1978.

British sailor Ellen MacArthur became the fastest solo sailor to sail around the world in 2005 when she traveled over 31,000 miles in 71 days, 14 hours, 18 minutes 33 seconds.

Brauer hopes to serve as the same inspiration as the sailing pioneers.

“I push so much harder when someone is like, ‘you can’t do that.’ And I’m like, ‘OK, watch me,’” she told NBC. “It would be amazing if there was one other girl who saw me and said, “Oh, I can do that too.”

Share this article:

Advertisement

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Entertainment

Sailor Cole Brauer Is Making History as the First U.S. Female to Race Solo Across the Globe: 'It's a Dream Come True' (Exclusive)

In second place in the Global Solo Challenge, Brauer, 29, rounded Cape Horn off the Chilean coast on Jan. 26, 2024

COLE BRAUER OCEAN RACING

Fifteen-foot waves crashed over the deck of Cole Brauer’s 40-foot racing yacht, First Light , in the turbulent Indian Ocean as she tried to maintain her balance in the cramped cockpit in the stern.

The usually-trustworthy boat’s autopilot feature had broken down, forcing the 29-year-old skipper to steer the shaky tiller with her legs and man the lines of two sails with each arm while careening through one of the most treacherous stretches of the ocean. Solo.

“I'm trying to get rid of the sails because I can't control the boat,” the Long Island, New York, native tells PEOPLE, recalling the harrowing experience in December.

“But I can't leave the helm.” she says. “It's like driving a car on the highway and you don't have an accelerator or brakes. All you've got is this loose steering wheel. I was free-falling down waves, going so fast, I hit the maximum speed I've ever hit on this boat, just flying and then free-falling.”

Her oceanic roller coaster ride became extra challenging because she’d just injured — or possibly cracked — a rib when rough seas hurled her across the cabin earlier in the trip. “Every movement is this shooting pain,” she says.

But Brauer forged on. Using both arms and legs “like Mrs. Octopus,” she says, she took down the sails, strapped everything down tight and let the boat free float to allow her to fix the autopilot problem. “I fixed it,” she says. “It took me two days to resolve the issue.”

While her team back in the U.S. was monitoring the situation from afar via the Starlink satellite internet service, in that moment Brauer had no choice but to rely on herself. “It’s not like you can quit,” she says. “You're in the middle of the ocean. There is no quitting. No one's going to come and save you. So it’s like, ‘Suck it up. Fix the problem.’ In the end, it's just you. You have to keep moving forward.”

This can-do, persevere-at-all-costs attitude is what has made Brauer a rising star in the racing world. It’s also what has kept her going as she works toward an ambitious, history-making goal: being the first American woman to race solo nonstop around the world.

"We're doing it!" says Brauer, speaking about herself -- and First Light.

Of the 16 skippers in the inaugural Global Solo Challenge, a non-stop race that starts and ends in A Coruña, Spain, she is the only female and the youngest. And, at 5-feet-two-inches and 100 lbs., she notes, the smallest — something she sees as an asset.

“To make it out here as a hundred-pound girl is a dream come true,” she says.

Starting on Oct. 29, 2023, Brauer and First Light , along with six other boats, set sail from A Coruña. She traveled down the west African coast, rounding South Africa's Cape of Good Hope, before heading to the Indian Ocean, where she rounded Cape Leeuwin in Australia before setting out across the Pacific toward South America.

On Jan. 26, she hit what is considered the “Everest” of her career by rounding Chile’s Cape Horn, surviving the notoriously deadly Drake Passage, the turbulent strait connecting the Pacific and Atlantic between Cape Horn and the South Shetland Islands, just above Antarctica.

Becoming a member of that exclusive club was no easy feat. “It's treacherous,” she says. “All sailors know it’s the hardest ocean in the world. The reason why the Southern Ocean is so respected by sailors is because there's so many people that lost their lives to the Southern Ocean.”

Over a period of about four months, she and the other skippers are covering 27,000 miles in the race. With a staggered start, the boats will finish on different dates. She expects to finish in early March.

As of press time, she was in second place behind Mowgli, helmed by French skipper Philippe Delamare. The third-place boat was more than 1,400 nautical miles behind her and hadn’t yet reached Cape Horn.

Being raised in a non-sailing family — her dad is a contractor and her mom once owned a small retail store that sold dance and exercise-wear — with no connections in the tight-knit, male-dominated world, she is proud of how far she has come.

This July, she raced in the Bermuda One-Two, not only winning the yacht race, but becoming the first female to do so. For her, it was a turning point in her career.

Before that, even though she had raced before, she says, "Nobody took me seriously. I was always just the 'girl in the van.'" (Back in the U.S., she lives out of a van, sometimes in Maine, where her parents live, or in coastal cities such as Newport, Rhode Island, where she prepped First Light, and Mystic, Connecticut.)

"Having the win come out of it said, 'She's not just messing around. We get what you've been do all these years.'"

At the same time, she says, "It shows we women can do anything that you guys can do. We don't have to keep following in your footsteps. We are the ones that are leading the charge now.”

The Calm After the Storm

PEOPLE spoke to Brauer via Zoom on in a rare moment of quiet, when she and First Light were about 400 miles northeast of the Falkland Islands in the south Atlantic, off the coast of Argentina.

“It was blowing 35 knots last night, and then that front went over me and now it's like glass outside,” she says, going on deck and showing off the 360-degree view of nothing but ocean, wet laundry draped over the deck and drying in the sun — and a bird floating on the surface nearby. “He's been with us” — meaning her and the boat — “for about three hours now,” she says. “He just sits right next to me and hangs out.”

The serenity gave her the chance to take a well-deserved breather, which included a full-body “sun shower” on deck using water from a solar-heated pouch instead of out of a bucket. “It’s a spa day,” she says with a laugh. “I've cleaned up a little bit. I'm eating, I'm trying to be a little more human today versus the last two months feeling like an astronaut.”

Serena Vilage

Sailing across the southern seas — the stretch from the Cape of Good Horn in South Africa to the Indian Ocean to the South Pacific through Chile with Antarctica to the south — “is like being on Mars, but much more wet,” she explains. “It's desolate, there's nothing around, and you are out in the middle of nowhere.”

Cold and violent, the storms, she says “just come and come and all you're doing is just trying to avoid them the best that you can. Sometimes you can do a really good job avoiding them, and then sometimes they just run you right over. Then you have to deal with the mess afterwards of cleaning up the boat and making sure that you're still alive.”

During her journey, she made it to Point Nemo in the South Pacific, the part of the ocean that’s farthest from any land. “The closest to humans that I was was the International Space station,” she says.

The calmer waters of the South Atlantic pose their own challenges. “You get into light winds like this, or no wind, and a lot of people go crazy,” she says. “But I'm really happy to be in this light wind, because it gives me a second to relax after dealing with hurricane force winds over and over and over.”

Netflix and Facebook Marketplace on the High Seas

For Brauer, a typical day during the race means waking up at sunrise — going by UTC or Coordinated Universal Time that's five hours ahead of Eastern Time.

“I'll get up, I'll walk outside and just check things and make sure there's nothing floating in the water behind me," she says. "You'll find random things off the boat that are dragging behind you after a crazy night.”

Among them, “trash dragging on the rudders,” she says, “and I have lines from the boat that are just off just dragging behind me.”

She gets situated for the day, first by checking the weather. “I always download that pretty much immediately as I get up in the morning to find out what's going to happen,” she says. “I'm downloading weather all the time, as much as I possibly can, especially with Starlink now.”

She meets virtually with her team every day, checking in with them in a group chat. This includes her weather router, her project manager and a medic who keeps track of her health.

She does a “little bit of an exercise to get the joints moving. There's no heat on the boat, so it's just damp, cold, and you feel decrepit."

Next comes breakfast, which is usually tea and oatmeal. “I'm actually running low on oatmeal. It's really depressing.”

She posts daily updates of her journey on Instagram and on her website colebraueroceanracing.com .

She cooks by heating up water in a jet boil, adding it to pre-packaged, freeze-dried foods. One of her favorite dinners is Peak Refuel’s sweet pork and rice.

When it’s time to go to bed, she curls up in her bed — a sleeping bag atop a beanbag tucked into the engine compartment, and four fleece pillows custom-made by her friend Jeff Samas of Straight Line Fabrication in Somerset, Mass.

Near her bed is her navigation station, with a computer screen in the center. “It has radar and the cameras,” she says. “I have one that faces outside. And so I can watch outside from my bed.”

When she’s not tussling with hurricane-like winds, she enjoys her down-time. “I read books a lot,” she says. “I listen to a lot of podcasts. Music is massive, I always have my speaker on. I think it helps with life.”

While Amazon obviously can’t deliver the chocolate or oatmeal she wants, she still has Netflix. “I've watched probably more Netflix movies than I have ever watched,” she says. “Right now I am rewatching rom-coms from the 2000s. Today’s movie is Pretty Woman.”

Mostly, though, she attributes keeping in touch with her trusted team and longtime friends to help her through loneliest moments — all thanks to technology.

“It has been great, definitely, to communicate with people,” she says. “I had a dinner party with a couple of my girlfriends for one of my girlfriend's birthdays, and they dressed up, and I ate pasta here, and we chatted, and they had dessert, and I ate the rest of my chocolate bar. That was the end of my chocolate bar.”

She also keeps in touch with her parents, who live in Maine. “I FaceTime my mom every morning,” she says.

Cole Brauer

While floating in her “40-foot bubble” has allowed her to tune out most of the modern world, she can still take care of the tasks. “With Starlink, I was on the phone with my dad yesterday, because I want to buy a car,” she says. “I've been on Facebook Marketplace looking for a little Mini Cooper.”

She adds, “I'm having my dad go and test drive these little couple of grand Mini Coopers or whatnot. So that's the weird part about you're still living the same life, you were just doing it from afar.”

One of the perks of living on a boat in the middle of the ocean is the ability to marvel at some of the most stunning sunsets on Earth.

Or to just kick back, soak in the starry heavens above, and just be.

“I have this little black mat that I kind of lay out on,” Brauer says. “I bring my pillows and my sleeping bag and then sometimes I'll snuggle in right on the side of the cockpit.” She adds, “And that's so nice because in the tropics, you have the Milky Way and it comes down and it's like a waterfall and you can't tell where the ocean starts and the sky ends.”

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE's free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer, from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

Related Articles

- Share full article

Alone on the Ocean, With 400,000 Friends

As Cole Brauer sped to the finish of a solo race around the world, she used Instagram to blow up sailing’s elitist image.

Before she could begin the Global Solo Challenge, a nonstop solo race around the world, Cole Brauer had to sail First Light, a 40-foot yacht, from Rhode Island to Spain. Credit... Samuel Hodges

Supported by

By Chris Museler

- Published Feb. 29, 2024 Updated March 7, 2024

Video dinner parties, spa days, stuffed animals, favorite hoodies and cozy, colorful fleece blankets. Cole Brauer’s Instagram feed hardly feels like the work of someone racing a 40-foot sailboat around the world in the Global Solo Challenge. But Ms. Brauer, 29, is not an average ocean racer.

In 2022, Ms. Brauer had tried out for another competition, the Ocean Race, which is considered the pinnacle of professional ocean racing. Sailors in that race are highly trained, wear matching foul weather gear and have corporate sponsors. And most of them are men. Ms. Brauer, who had sailed thousands of miles on high performance ocean racing boats, felt she was ready to join their ranks.

But after competing in trials in France, Ms. Brauer was told she was “too short for the Southern Ocean” and was sent on her way.

In spite of her small stature — she stands 5 feet 1 inch — Ms. Brauer rounded Cape Horn, Chile, on Jan. 26, the last of the three great capes of her journey to finish the Global Solo Challenge. It is a feat most of the Ocean Race sailors picked instead of her have never even attempted. And despite being the youngest competitor in the race, she is ranked second overall, just days away from reaching the finish line in A Coruña, Spain.

Along the way, her tearful reports of breakages and failures, awe-struck moments during fiery sunrises, dance parties and “shakas” signs at the end of each video have garnered her a following that has eclipsed any sailor’s or sailing event’s online, even the Ocean Race and the America’s Cup, a prestigious race that is more well known by mainstream audiences.

“I’m so happy to have rounded the Horn,” Ms. Brauer said in a video call from her boat, First Light, after a morning spent sponging out endless condensation and mildew from its bilges. “It feels like Day 1. I feel reborn knowing I’ll be in warmer weather. The depression you feel that no one in the world can fix that. Your house is trying to sink and you can’t stop it.”

Shifting gears, she added, “It’s all getting better.”

Ms. Brauer’s rise in popularity — she has more than 400,000 followers on Instagram — has come as a surprise to her, but her achievements, combined with her bright personality, have struck a chord. And she has set a goal of using her platform to change the image of professional ocean sailing.

“Cole wants to prove you can go around the world and watch Netflix every once in a while and wear your pajamas,” said Lydia Mullan, Ms. Brauer’s media manager. “As for her mental health, she’s really creating a space in her routine for herself, to create that joy she hasn’t seen in other sailors.”

Four months after she began the Global Solo Challenge, a solo, nonstop race around the world featuring sailboats of different sizes, Ms. Brauer is holding strong. Sixteen sailors began the journey and only eight remain on the ocean, with the Frenchman Philippe Delamare having finished first on Feb. 24 after 147 days at sea.

Ms. Brauer, who was more than a week ahead of her next closest competitor as of Thursday morning, is on track to set a speed record for her boat class, and to be the first American woman to complete a solo, nonstop sailing race around the world.

Her Authentic Self

Ms. Brauer has been happy to turn the image of a professional sailor on its head. Competitors in the Ocean Race and the America’s Cup tend to pose for static social media posts with their arms crossed high on their chests, throwing stern glares. Ms. Brauer would rather be more comfortable.

She brought objects like fleece blankets on her journey, despite the additional weight, and said solo sailing has helped give her the freedom to be herself.

“Without those things I would be homesick and miserable,” she said of her supply list. “We need comfort to be human. Doing my nails. Flossing. It’s hard for the general public to reach pro sailors. People stop watching. If you treat people below you, people stop watching.”

Other female sailors have noticed the same disconnect. “The year I did the Vendée Globe, Michel Desjoyeaux didn’t mention that anything went wrong,” Dee Caffari, a mentor of Ms. Brauer’s who has sailed around the world six times, said of that race’s winner. “Then we saw his jobs list after the finish and we realized he was human.”

Ms. Brauer, as her social media followers can attest, is decidedly human.

They have gotten used to her “hangout” clothes and rock-out sessions. Her team produces “Tracker Tuesdays,” where a weather forecaster explains the routes Ms. Brauer chooses and why she uses different sails, and “Shore Team Sunday,” where team members are introduced.

“In the beginning I looked at what she was doing, posting about washing her knickers in bucket and I was like, ‘No! What are you doing?’” Ms. Caffari said. “I’ve been so professional and corporate in my career. She’s been so authentic and taken everyone around the world with her. Cole is that next generation of sailor. They tell their story in a different way and it’s working.”

Finding a Purpose

Ms. Brauer was introduced to sailing at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Those days of casual racing on the turquoise waters of Kaneohe Bay informed her vision of an inclusive sailing community. That image was shattered when she came to the mainland to try her hand at professional sailing.

“When I came to the East Coast it was so closed off,” she said of those early experiences. “I couldn’t get a job in the industry. Pro sailors were jaded. They didn’t want anyone to take their job. It’s a gig-based economy. Competition, we’re pinned against each other, especially women in high-performance sailing since there are fewer of us.”

“This whole process of being a pro sailor over the past five years, I feel mentally punched in the face and my legs kicked out from under me,” she added. “I screamed and I cried. Without those experiences I wouldn’t be as mentally tough. It made me callused.”

A big break happened when she landed a gig as boat captain for Michael Hennessy’s successful Class40 Dragon. The boat was a perfect platform to hone her ocean sailing skills as she ripped up and down the East Coast delivering it to races, often alone, pushing Dragon to its limits. Her Instagram posts of those adventures drew attention, and she was invited to tryout for the Ocean Race, a fully crewed race around the world in powerful 65-footers.

“I was crushed,” Ms. Brauer said of being rejected after the trials.

Ms. Brauer, though, found a new purpose. After months of living in her van and working on Dragon, she found a benefactor in F.K. Day, the president of World Bicycle Relief and the executive vice president of SRAM Corporation, who, along with his brother Lincoln, agreed to buy a boat and fund a massive refit for the Global Solo Challenge, which was only three months away.

Conducting the hurricane of activity last summer in Newport, R.I., Ms. Brauer knew this was her moment to shine. But representatives for her new sponsors had reservations about her bold social media experiment.

“I got a massive pushback: ‘How can you be so vain. This isn’t important. We don’t want to pay for this,’” she said. “I said none of this is going to matter if the world can’t see it.”

Her boat was covered with cameras her shore team could monitor, with technology allowing for constant recording that could be used to capture unexpected twists. Ms. Brauer got some immediate traction, but nothing prepared her for the numbers she would hit once the race began.

“We were taking bets in Spain,” said Ms. Brauer, who had to sail First Light nearly 3,000 miles from Newport to Spain as a qualifier for the race. “There was a photo of me excited we hit 10,000 followers. Ten thousand for a little race? That’s massive.”

A few months later she has 40 times that count.

A Dangerous Journey

Only a handful of solo ocean racers have been American, all of whom being male. Now Ms. Brauer has a larger following than any of them, pushing far beyond the typical reach of her sport.

“This is a really good case study,” says Marcus Hutchinson, a project manager for ocean racing teams. “For me she’s an influencer. She’s a Kardashian. People will be looking for her to promote a product. She doesn’t need to worry about what the American sailors think. That’s parochial. She has to split with the American environment.”

Unlike her peers, Ms. Brauer is happy to do some extracurricular work along the way toward goals like competing in the prestigious Vendée Globe. “I’m part of the social media generation,” she said. “It’s not a burden to me.”

The playful videos and colorful backdrop, though, can make it easy for her followers to forget that she is in the middle of a dangerous race. Half her competitors in the Global Solo Challenge have pulled out, and ocean races still claim lives, particularly in the violent, frigid storms of the Southern Ocean.

“She was apprehensive,” Ms. Caffari said of Ms. Brauer’s rounding Cape Horn. “I told her: ‘You were devastated that you didn’t get on the Ocean Race. Now look at you. Those sailors didn’t even get to go to the Southern Ocean.’”

The question now is how Ms. Brauer will retain her followers’ desire for content after the race is over.

“She will be unaware of the transition she went through,” Mr. Hutchinson said. “She’s become a celebrity and hasn’t really realized it.”

Ms. Brauer, however, said she received as much from her followers as she gave them.

“They are so loving,” she said. “I send a photo of a sunset, and they paint watercolors of the scene to sell and raise money for the campaign. When I start to feel down, they let me stand on their shoulders.”

Explore Our Style Coverage

The latest in fashion, trends, love and more..

The Uncool Chevy Malibu: The unassuming car, which has been discontinued by General Motors, had a surprisingly large cultural footprint .

A Star Is Born: Marisa Abela was not widely known before being cast as the troubled singer-songwriter Amy Winehouse in “Back to Black.” That’s over now .

A Roller Rink’s Last Dance: Staten Island’s Roller Jam USA closed for good after almost two decades. Here’s what some patrons had to say on its final night .

The First Great Perimenopause Novel: With her new book, “All Fours,” Miranda July is experimenting again — on the page and in her life.

Mocktails Have a New Favorite Customer: As nonalcoholic cocktails, wines and beers have become staples on bar menus across America, some children have begun to partake .

Advertisement

She’s the first American woman to sail around world solo in race — and she’s from Maine

A s the sun rose, only one mile separated Cole Brauer from the coast of A Coruña in Spain, where a crowd of supporters eagerly awaited her arrival after 130 days alone at sea. The 40-foot yacht First Light sliced through the waves, its blue and red sails emblazoned with “USA 54″ billowing against the wind. Victory in sight, Brauer stood at the bow and spread her arms wide, a safety flare sparkling in each hand. As she neared the finish line, the 29-year-old sailor hollered and cheered, flashing a wide smile.

At 8:23 a.m. on March 7, Brauer made history. Four months after setting sail from A Coruña for the Global Solo Challenge , Brauer became the first American woman to race around the world without stopping or assistance. The youngest skipper and the only female competitor, Brauer finished second out of 16 racers.

“I’m so stoked,” Brauer, of Boothbay Harbor , Maine, said in a livestream as she approached the end . She wore a headlamp over her beanie with the words “wild feminist” across the top, and a couple of boats trailed her. “I can’t believe it. I still feel like I’ve got another couple months left of this craziness. It’s a really weird feeling.”

She circumnavigated the globe by way of the three great capes — Good Hope, Leeuwin, and Horn — headlands that extend out into the open sea from South Africa, Australia, and Chile, respectively, and are notorious for presenting a challenge to sailors. Throughout, Brauer documented the arduous 30,000-mile journey in full on her Instagram feed. She amassed hundreds of thousands of followers, introducing many of them to the sport and upending stereotypes of a professional sailor.

Brauer, who is 5 feet 2 inches tall and weighs just 100 pounds, has long defied expectations and overcome skepticism in reaching the pinnacle of the yachting world.

Advertisement

“I’ve always been not the correct mold. I had a guy who used to always tell me, ‘You’re always on trial because the second you walk in the door, you have three strikes against you. You’re young, you’re a woman, and you’re small,’” she recalled in a recent interview. “Now with my platform, I don’t have to be as careful about what I say or do because people care about me because of me — not because I’m a sailor.”

In her videos documenting her long days at sea, she was often vulnerable, crying into the camera when First Light had autopilot issues and sea conditions caused the boat to broach , throwing her hard against the wall and bruising her ribs. She was giddy, showing off her new pajamas on Christmas Eve and dancing in a pink dress on New Year’s Day . As her popularity soared, she was a guide for the uninitiated, providing a breakdown of her sailing routes , her workouts and meals, and how she replaces equipment alone .

A native of Long Island, N.Y., she spent her childhood on the water, kayaking with her sister across the bay to school and finding comfort in the roll of the tide. She went to the University of Hawaii at Manoa , where, longing to be back on the ocean, she joined the sailing team. Brauer learned quickly, becoming a standout and winning the school’s most prestigious athletics award.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by COLE BRAUER OCEAN RACING (@colebraueroceanracing)

After college, she moved to the East Coast, hoping to start a career in sailing. But she found it difficult to break into the male-dominated industry.

“It was very difficult. I got a lot of ‘nos’. A lot of, ‘No way, we want nothing to do with you. You’re a liability,’” Brauer recalled.

Undeterred, she took whatever job she could, often for little pay.

Brauer found her footing in Boothbay Harbor , where her parents, Kim and David, were living. She coached the junior sailing team at the yacht club and met yacht captain Tim Fetsch, who became her mentor. While talking with Fetsch one night over dinner, Brauer shared her goal of competing in the prestigious Ocean Race , known as “sailing’s greatest round-the-world challenge.”

He sent her “ Taking on the World ,” Ellen MacArthur’s book on finishing the Vendée Globe, a solo round-the-world race, at 24. She cried while reading it.

“They allowed me to flourish in Maine,” she said.

With Fetsch, she delivered boats to Mystic, Conn., and Newport, R.I., a sailing capital where Fetsch introduced her to his connections and she “was accepted pretty early on as as a worker bee.”

Her big break arrived when she became the boat captain for Michael Hennessy’s Class40 Dragon . She spent several years captaining Dragon and delivering it to races along the East Coast and the Caribbean.

In 2022, she was invited to try out for the Ocean Race. But after the two-week trials in France , where she sailed with a fully crewed team, she was dismissed. They told her she was too small.

“They didn’t want the 100-pound girl unless you were, you know, one of those big guys’ girlfriends, and I was not going to be that,” she said.

Describing the story to a couple of friends after the trials, Brauer made a vow — “I guess I just gotta go around the world alone.”

“It’s almost good that it happened because I needed that to push me over the edge,” she said. “I needed them to make me feel so little that I would do anything to be big.”

Later that year, Dragon was sold to a pair of brothers, who renamed it First Light and said Brauer could keep sailing it for the season. In June, Brauer and her co-skipper, Cat Chimney, became the first women to win the 24th Bermuda One-Two Yacht Race . After the victory, Brauer was prepared to take a break from competition and enjoy a “gorgeous Newport summer.”

Her sponsors had other plans. “You need to take the momentum with this win,” Brauer recalled the brothers saying. “This is probably your one and only chance to really show the world, and we’re willing to help.”

She set her sights on the Global Solo Challenge . First Light underwent a refit. With little time to prepare, Brauer suffered panic attacks and became worryingly thin. But the sailing community rallied around her and she assembled her team.

“Newport said, ‘You are our child, and we’re going to take care of you,’” she recalled.

Brauer took off from Spain on Oct. 29, and her online profile began to rise as she chronicled the voyage. The sudden isolation was overwhelming at the start, bringing her to tears at least once a day.

At one point in the race, while bobbing along in the Southern Ocean, things looked bleak. She was in excruciating pain after being slammed into the side of the boat and could hardly move. First Light was having issues with its autopilot system and she kept having to replace deteriorating parts.

“It took the entire team and my own mental state and my mother and my whole family to kind of be like, ‘You’re tough enough, like you can do this. You can get yourself out of this,’” she said.

In a race where more than half the competitors pulled out, their boats unable to withstand the harsh conditions, Brauer often listened to music on headphones to lower her anxiety.

“This is your everything. You don’t want to lose it,” she said. “Mentally, no one in the entire world knows what you’re feeling. They can’t understand the weather or the wind patterns.”

Her team monitored her by cameras, and she spoke each day to those close to her, including her mom, whom she FaceTimed every morning (she used Starlink for internet access). Sometimes they would just sit in silence. Brauer found comfort interacting with her Instagram followers, who peppered her with questions about sailing terminology and sent her messages of affirmation.

She made a ritual of watching the sunset and sunrise, each different than the last.

“Those were the most magical moments,” she said. “No obstructions, no buildings, no cars to ruin the sound.”

As she approached the finish, she described how surreal it felt that the journey was about to be over.

“It’s such a weird feeling seeing everyone. I’m trying to learn how to interact again with people, so we’ll see how this goes,” Brauer said with a slight smile and laugh on her livestream. “I don’t really know how to feel. I don’t really know how to act. I don’t really know how to be.”

Shannon Larson can be reached at [email protected] . Follow her @shannonlarson98 .

Watch CBS News

Maine native hopes to be first American woman to complete solo race around the world in boat

By Laura Haefeli

February 2, 2024 / 6:28 PM EST / CBS Boston

BOSTON - A Maine woman is taking part in one of the most extreme sailing events on earth, sailing by herself on a 40-foot race boat around the world.

Cole Brauer has been away from home for three months already, three quarters of the way through the Global Solo Challenge. She's one of ten people participating in the race.

"The goal of this was always to be the first American woman to race solo around the world," said Brauer.

Brauer learned to sail when she was attending college in Hawaii. She fell in love with the sport and brought her skills home to Maine, where she began training for the four-month-long race around the world. She said the journey hasn't been easy.

"I think I'm doing much better now that I'm back in the Atlantic," said Brauer. "When I was in the southern ocean, it was really rough."

Two months in, Brauer crashed into the walls of her vessel after a massive wave slammed on top of the boat. She was left with bruised ribs and said she does have a team looking out for her.

"I have a medical team on staff and we have cameras on board so they can watch me 24/7," said Brauer.

Brauer is currently sailing 800 miles off the coast of Uruguay but the journey brings her to even more remote parts of the ocean, including Point Nemo, where she was closer to the International Space Station than any piece of dry land on earth.

"If someone needed to come out and get me, it could take upwards of a week."

The chaos is balanced with quieter moments of beautiful sunsets and wildlife coming by to visit but she said it does get lonely. The trip will soon come to an end and Brauer said she's dreaming of eating fresh food and seeing her family.

"So excited to have a cappuccino and a croissant, cannot wait" said Brauer.

Brauer is expected to finish her race in Spain in about a month.

Featured Local Savings

More from cbs news.

Family of Lewiston, Maine gunman testifies and says more could have been done

Day care owner, 3 employees accused of spiking kids' food with melatonin

Newton woman teaching others to knit after it improved her mental health

Woman says she was raped by Brockton killer who's been on the loose for 10 years

Cole Brauer Becomes First American Woman to Sail Solo Around the World

The 29-year-old sailor placed second in a grueling four-month circumnavigation race across some 30,000 miles of open water.

AJ McDougall

Breaking News Reporter

Sebastien Salom-Gomis/AFP via Getty Images

A sailor went to sea, sea, sea—and became the first American woman to sail alone non-stop around the world. Cole Brauer, 29, of Long Island, New York, made history on Thursday after sailing into A Coruńa, Spain, four months after striking out of the same harbor on the Global Solo Challenge, a treacherous 30,000-mile journey that saw her traverse three oceans.

Brauer, 5-foot-2 and 100 pounds soaking wet, was the youngest and only female competitor among the 16 people who competed in the challenge. She placed second in the race, which took her 130 days to complete.

She and her 40-foot sailboat, dubbed First Light, were met by a crowd of jubilant family, friends, and admirers. “This is really cool and so overwhelming in every sense of the word,” NBC News quoted her as saying as she drank Champagne from her trophy.

Brauer set out from A Coruńa on Oct. 29, sailing down Africa’s western coast and around the Cape of Good Hope before making her way east towards Australia. She rounded South America’s notorious Cape Horn before finally heading back towards Spain.

She kept her audience of more than 400,000 Instagram followers up to date along the way, posting frank updates as to the brutal conditions she was enduring. In one terrifying caught-on-camera moment, Brauer was thrown across her boat as it was tossed by 30-foot waves, landing so hard that one of her ribs cracked.

“I don’t want you guys to think I’m like Superwoman or something,” she said in a video posted shortly after, saying she had to keep making repairs and recalibrations despite feeling “broken.”

“It’s all part of the journey, and I’m sure I’ll be feeling better once the work is done and I’ve gotten some sleep,” she wrote in the caption. “But right now things are tough.”

Speaking on NBC’s Today on Thursday from Spain, Brauer explained to the hosts, “There really is no option at that point. You’re so far away from land—there is no rescue, there’s nobody to come and grab you. You kinda just have to keep moving along.”

More than half of the Global Solo Challenge’s sailors have dropped out so far, according to NBC News. Brauer said she hoped that her big finish could inspire younger women to get into sailing—and start busting records of their own. “It would be amazing if there was just one girl that saw me and said, ‘Oh, I can do that too,’” she told NBC.

With her voyage at an end, Brauer told WBZ-TV on Thursday that she was excited to enjoy a cappuccino and croissant on dry land. It seemed like she wasn’t quite ready to rest on her laurels, however. “It hasn’t really hit me yet. Everyone’s so excited, but for me it hasn't really sunk in that I now hold these records,” she said in a statement. “It just feels like I went for a little sail, and now I’m back.”

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here .

READ THIS LIST

The Vendée Globe switches to American time

Bpgo, from the figaro circuit to the vendée globe, icebergs, navigation and sea level.

One globe, one ocean

The Vendée Globe aims to use the media impact of the event to raise public awareness of ocean conservation throughout the round-the-world race. By sailing around the world, the Vendée Globe sailors are highlighting the fragility of our oceans faced with global warming. They are direct witnesses to the changes underway, particularly around Antarctica, a region that is under particular threat.

Soft mobility

The Vendée Globe adventure doesn't start in Les Sables d'Olonne! It starts from home, by using a low-carbon mode of transport to get to the race village. The organisers have set up a mobility committee to bring together all the public and private players involved and propose soft mobility solutions for getting to the village.

44 candidates

Fabrice Amedeo

Romain Attanasio

Éric Bellion

Yannick Bestaven

Jérémie Beyou

Arnaud Boissières

Louis Burton

Conrad Colman

Antoine Cornic

Manuel Cousin

Clarisse Crémer

Charlie Dalin

Samantha Davies

Violette Dorange

Benjamin Dutreux

Benjamin Ferré

Sam Goodchild

François Guiffant

James Harayda

Oliver Heer

Boris Herrmann

Isabelle Joschke

Jean Le Cam

Tanguy Le Turquais

Nicolas Lunven

Sébastien Marsset

Paul Meilhat

Justine Mettraux

Giancarlo Pedote

Yoann Richomme

Thomas Ruyant

Damien Seguin

Kojiro Shiraishi

Sébastien Simon

Maxime Sorel

Guirec Soudée

Nicolas Troussel

Denis Van Weynbergh

Szabolcs Weöres

What is the Vendée Globe?

The Vendée Globe is a single-handed, non-stop, non-assisted round-the-world sailing race that takes place every four years. It is contested on IMOCA monohulls, which are 18 metres long. The skippers set off from Les Sables-d'Olonne in Vendée and sail around 45,000 kilometres around the globe, rounding the three legendary capes (Good Hope, Leeuwin and finally Cape Horn) before returning to Les Sables d'Olonne. The race has acquired an international reputation, attracting skippers from all over the world. Beyond the competition, it is above all an incredible human adventure.

Stay tuned #VG2024

Our partners, title partner, major partner, premium partner, official partners.

Official Suppliers

Un partners, ocean partners.

Technical Suppliers

Around The World Solo In a Sailboat: What Does It Take?

It takes stamina, humor, planning—not to mention hanging from a line 60 feet up, over waves the size of a house, in gale-force winds

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/WendyClarke1.JPG)

Wendy Mitman Clarke

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/80/69803067-bb99-47d3-9d9d-2f7c9ececdea/istock-921302160.jpg)

Imagine being alone on the ocean for five or ten weeks, sailing in snow, ice and spray cruel as needles. The wind belts you like a prizefighter. The boat is your only haven, yet it throws you like a bronco. Amid all this you must eat, sleep, navigate, find the quickest route and handle every problem yourself, from sprained wrist to snapped mast. This is the endurance test facing the 20 competitors in the BOC Challenge — a single-handed, round the world race that takes place every four years. The sailors began in Charleston, South Carolina, and after stops in three ports along the 27,000-mile route, they will end up in Charleston next month.

One of the racers, Steve Pettengill of Middletown, Rhode Island, gives a nearly day-by-day account of what it takes to prepare for and sail one leg of the race, from Cape Town, South Africa, to Sydney. We're "on board" as he stocks his boat, Hunter's Child, with freeze-dried meals and favorite cassettes, fine-tunes his computerized navigation station, battles freezing rain and stomach churning storms while making repairs and learns the sometimes sad fate of his competitors.

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/WendyClarke1.JPG)

Wendy Mitman Clarke | READ MORE

Wendy Mitman Clarke is director of media relations for Washington College in Chestertown, Maryland and a lifelong sailor obsessed with the ocean and all the wonder and weirdness that lives within it. Besides Smithsonian, her non-fiction stories have appeared in Preservation , and Chesapeake Bay Magazine . She's also a published poet.

Our interview with Cole Brauer, first American woman to sail around the world solo

by Studio10

Studio10 host Christina Erne sits down with Cole Brauer, the first American Woman to sail around the world solo. Brauer completed a 130 day journey around the world, and now she’s back telling us all about her adventures.

She talks about being on her own for 130 days. Brauer grew up being outside and on the water. As a child, she speaks with Christina about enjoying riding her kayak to school! There are opportunities for people to hear Brauer talk about her experiences out on the water. One of those events is happening at Roger Williams University tonight, May 15th at 6:00pm. More information on getting tickets can be found at the link to their website, available here!

See what it’s like to sail solo at full throttle

Vendee globe highlights.

Watch some of the best moments from the Vendee Globe solo round-the-world sailing race.

The Vendee Globe started in Les Sables d’Olonne

© Jean-Marie Liot/DPPI/Vendee Globe

Alan Roura of La Fabrique sailing alone

© Alan Roura/La Fabrique/Vendee Globe

Banque Popular spotted off Cape Verde from a plane

© Marine Nationale/Vendee Globe

Heading south to the Southern Ocean

© Bertrand de Broc/MACSF/Vendee Globe

This is the most remote place on Planet Earth

These waves are the mountains of the sea, watch these boats catch some serious waves, this crew sailed 1062km to bermuda in gnarly seas.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

This race is a nonstop sail around the world. Cassette tapes are allowed, but no GPS

Scott Neuman

South African sailor Kirsten Neuschafer, the only woman in the 2022 Golden Globe Race. All but three of her 15 competitors in the grueling months-long competition have been forced to drop out. Aida Valceanu/GGR/2022 hide caption

South African sailor Kirsten Neuschafer, the only woman in the 2022 Golden Globe Race. All but three of her 15 competitors in the grueling months-long competition have been forced to drop out.

Somewhere in the Southern Pacific Ocean, Kirsten Neuschafer is alone on her boat, Minnehaha, as she tries to outmaneuver the latest storm to cross her path as she approaches Cape Horn.

Instead of sailing directly for the tip of South America, she's spent the past day heading north in an effort to skirt the worst of the oncoming weather. The storm is threatening wind gusts up to 55 miles per hour and seas building to 25 feet.

Her plan, she explains over a scratchy satellite phone connection, is to get away from the eye of the storm. "The closer I get to the Horn," she says, "the more serious things become, the windier it becomes."

But there's no turning back. That's because Neuschafer is battling to win what is possibly the most challenging competition the sailing world has to offer — the Golden Globe Race. Since setting off from the coast of France in September, Neuschafer, the only woman competing, has left all rivals in her wake. Of the 16 entrants who departed five months ago, only four are still in the race, and for the moment at least, she's leading.

The race is a solo, nonstop, unassisted circumnavigation, a feat first accomplished in 1969, the same year that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the moon. Since then, more people have traveled to space than have done what Neuschafer is hoping to accomplish.

The race is a throwback in most every way. Unlike its more famous cousin, the Vendée Globe solo nonstop race with its purpose-built vessels made for speed, Golden Globe entrants sail low-tech boats that wouldn't look out of place in any coastal marina. And they do so without modern electronic aids — no laptops or electronic charts, radar or sophisticated weather routing. To find their position at sea, participants instead rely on navigating by the sun and stars and simple speed calculations.

Racers don't do it for the money. The prize of 5,000 pounds (about $6,045) is the same as it was in the 1960s and is not even enough to cover entry fees. The real lure is the challenge.

"The single-handed aspect was the one that drew me," Neuschafer, who is from South Africa, says of her decision to enter.

"I really like the aspect of sailing by celestial navigation, sailing old school," she says, adding that she's always wanted to know "what it would have been like back then when you didn't have all the modern technology at your fingertips."

Satellite phones are allowed, but only for communication with race officials and the occasional media interview. Each boat has collision-avoidance alarms and a GPS tracker, but entrants can't view their position data. There's a separate GPS for navigation, but it's sealed and only for emergencies. Its use can lead to disqualification. Entrants are permitted to use radios to communicate with each other and with passing ships. They're allowed to briefly anchor, but not get off the boat nor have anyone aboard. And no one is allowed to give them supplies or assistance.

The race motto, "Sailing like it's 1968," alludes to the fact that it's essentially a reboot of a competition first put on that year by the British Sunday Times newspaper. In it, nine sailors started, and only one, Britain's Robin Knox-Johnston , managed to complete the first-ever nonstop, solo circumnavigation, finishing in 312 days. Despite leading at one point, French sailor Bernard Moitessier elected to abandon the race in an effort, he said, to "save my soul." Yet another, British sailor Donald Crowhurst , died by suicide after apparently stepping off his boat.

Bringing the race back in 2018 for its 50th anniversary was the brainchild of Australian sailor and adventurer Don McIntyre, who describes the competition as "an absolute extreme mind game that entails total isolation, physical effort ... skill, experience and sheer guts."

"That sets it apart from everything," he says.

For sailors, it's the Mount Everest of the sea

Neuschafer, 40, is a veteran of the stormy waters she's presently sailing, having worked as a charter skipper in Patagonia, the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and Antarctica. Although she's been around Cape Horn before, this time is different, she says.

Previously she's been around "the Horn" when she could choose the conditions. But nonstop from the Pacific, with limited weather information, "I'd say, it's a notch up on anxiety. It's almost like ... trying to reach the peak of Everest," she says.

Finnish sailor Tapio Lehtinen's boat sank in November off the southern tip of Africa. He was rescued with the help of fellow racer Kirsten Neuschafer. Aida Valceanu/GGR2022 hide caption

Finnish sailor Tapio Lehtinen's boat sank in November off the southern tip of Africa. He was rescued with the help of fellow racer Kirsten Neuschafer.

Probably the most harrowing moment so far in this year's race came in November, when Neuschafer sailed 100 miles, staying at Minnehaha's helm through the night to rescue Finland's Tapio Lehtinen — one of the finishers in the 2018 race. She plucked him from a life raft some 24 hours after his boat, Asteria, sank in the southern Indian Ocean.

For the rescue, race officials broke protocol and allowed her to use GPS and gave her a time credit on the race. "I basically sailed throughout the night and by morning I got within range of him," she says.

Spotting Lehtinen's tiny life raft amid 10-foot waves was far from easy, Neuschafer says. "He could see ... my sail [but] I couldn't see him, not for the life of me." She later managed to transfer him to a freighter.

That incident reinforced for her how things could change at any moment. In the Golden Globe, she says, "a large proponent of it is luck."

The days can be serene, but also isolating

The drama of such days at sea is offset by others spent in relative peace. A typical day, if there is such a thing, starts just before sunrise, she says, "a good time to get the time signal on the radio so that I can synchronize my watches," which she needs for accurate celestial navigation.

"Then ... I'll have a cup of coffee and a bowl of cereal, and then I'll wait for the sun to be high enough that I can take a reasonable [sextant] sight." A walk around the deck to see if anything is amiss and perhaps a bit of reading — currently it's The Bookseller of Kabul by Norwegian journalist and author Asne Seierstad — before another sight at noon to check her position.

Or perhaps some music. It's all on cassette, since competitors aren't allowed a computer of any kind. As a result, she's listening to a lot of '80s artists, "good music that I ordinarily wouldn't listen to," she says.

The isolation was more difficult for American Elliott Smith, who at 27 was the youngest entrant in this year's race. He dropped out in Australia due to rigging failure.

Elliott Smith, a 27-year-old originally from Tampa, Fla. A rigging failure forced him to quit in Australia. Simon McDonnell/FBYC hide caption

Elliott Smith, a 27-year-old originally from Tampa, Fla. A rigging failure forced him to quit in Australia.

Reached in the Australian port city of Fremantle, the surfer-turned-sailor from Florida says he doesn't entirely rule out another try at the race in four years. But for now, he's put his boat, Second Wind, up for sale. He seems circumspect about the future.

"It was really obvious that I stopped enjoying the sailing at some point," he confides about the rigors of the race. "There were moments ... where I found myself never going outside unless I had to. I was like, 'I'm just staying in the cabin. I'm just reading. I'm miserable.' "

Smith says there were days when he would see an albatross, but was too mentally exhausted to appreciate the beauty of it. "I was like, 'This is so sad, you know?' Like, I've become complacent [about] something that most people would never even try, you know?"

Neuschafer, too, has had her share of frustrations. The latest was a broken spinnaker pole, which keeps her from setting twin forward sails on the 36-foot-long Minnehaha — her preferred setup for running downwind.

She's looking forward to finishing in early spring. But first, she still has to traverse the entire Atlantic Ocean from south to north.

"I'll get off and enjoy feeling the land beneath my feet." After that, she says, "the first thing I'd like to do is eat ice cream."

- around the world

Published on May 17th, 2024 | by Editor

Opening the door for circumnavigators

Published on May 17th, 2024 by Editor -->

As the last competitor in the Global Solo Challenge 2023-24 crawls up the South American coastline, plans are underway for the follow-up edition in 2027-28. Here’s an update from race organizer Marco Nannini:

Over 70 skippers have already registered their interest in the 2027-28 race with five having already taken the step to formally enter, others will wait till their plans to participate will firm up, with many window shopping for a boat. Others are studying the regulations to understand what modifications will be required to comply with the safety framework of the Event. Details of entrants will soon be made public on the event website.

We often spoke of the camaraderie that developed among competitors in this first edition, something we have always encouraged and which naturally occurred among like-minded sailors with a common dream. Despite staggered starts and a format that did not make it easy for all skippers to be together before any single start, the challenge and adventure they shared created a bond that transcended space and time. Somewhat as if only those who have been “out there” could really relate and understand one another.

We created a group chat for the 2027-28 skippers. Not every enquirer feels quite ready to commit to the project or wants to make their intentions public, but over 30 skippers have joined the group and over time will learn about one another’s project, boat, personal story as well as trials and tribulations to get to the start.

For the 2023-24 edition, we had received nearly 700 initial requests of information with a total of 54 skippers registering their interest in the competition. Twenty became full entrants and 16 managed to cross the starting line. Louis Robein, on arrival would become the seventh (and final) finisher of the first edition of the Global Solo Challenge highlighting the incredible attrition existing to go from dream to accomplishment.

Based on the experience of the first edition, we have every reason to believe the interest for the second Global Solo Challenge will grow considerably. With three and a half years to the start, the number of skippers already working on their projects gives us confidence in a progressive and sustainable growth of the event. More skippers are expected to start and, we think, more will also manage to finish as the experience and common issues faced by skippers can be passed on to future competitors.

Unlike established events with boats all belonging to the same class, like IMOCAs in the Vendée Globe, the waters of the Global Solo Challenge were, relatively speaking, fairly uncharted in terms of boat preparation for a non-stop circumnavigation on boats not specifically or solely designed for the task.

The history of solo circumnavigators, after the 1968 Golden Globe Race, takes us to the BOC Challenge of 1982-83 which had two classes for boats 32-44 feet, and 45-56 feet. The BOC Challenge was a solo race with legs, but it was effectively the precursor of the Vendée Globe. It is not a coincidence therefore that it was the winner of the first BOC, Philippe Jeantot, that went to launch the first edition of the Vendée Globe in 1989.

The BOC Challenge is probably the closest event in spirit to the Global Solo Challenge as entrants were not the modern elite sailing super-stars we see in the IMOCA circuit today with staggering budgets. The BOC remained accessible to sailors with the dream of a circumnavigation, and in the early editions, it was the go-to event to achieve the dream of a relatively affordable circumnavigation.